In 2020, we started a new tradition: Kicking off the new year by announcing our Women’s Running Power Women of the Year. The women featured in that group were the game changers, rule breakers, and trailblazers within our community; they were the ones to watch, to cheer for, and to be inspired by in this upcoming year.

For the third year in a row, we’re thrilled to announce a new group of honorees. In this year’s list, you’ll find some familiar faces along with a number of new additions. Last year, we broadened our scope beyond just athletes, because it’s not only the pros who are changing the game, it’s women within every corner of our community.

There are top athletes, of course, as well as powerful advocates who are speaking out about everything from domestic violence to racial inequality. We included leaders and innovators, as well as some of the most impactful voices of the women’s running world. Like the rest of us, the women in these pages identify as more than runners, but it’s through running that they’ve inspired us.

These 15 power women are reshaping the running industry for the better—and we can’t wait to watch the impact they make in the upcoming year.

Section divider

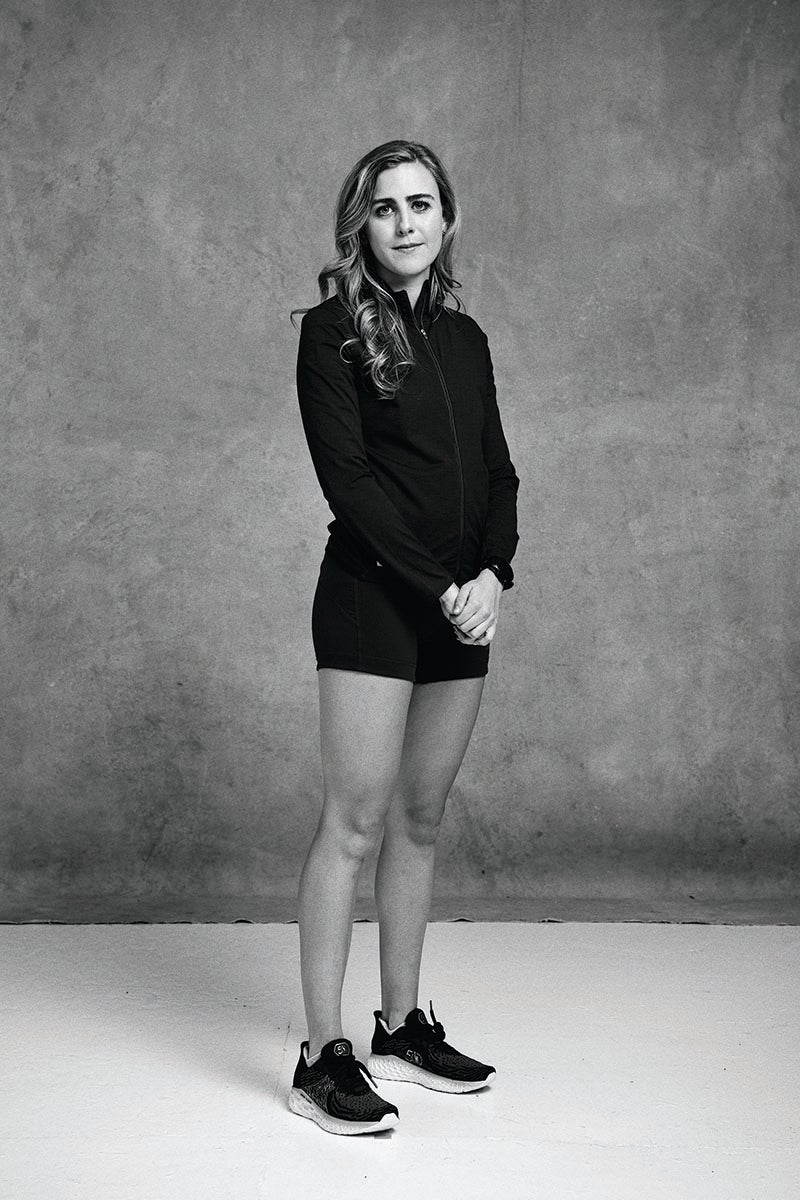

Mary Cain: In Her Power

In 2019, Mary Cain alleged abuse under the most renowned distance running coach in the country. Then she promised to do whatever she could to fix girls’ sports.

You probably remember her. It was 2012 or so and this high school girl from the New York City suburbs started popping up at pro meets and beating athletes 10 years older. Her post-race interviews were peppered with giggles, appearances by her stuffed duck named Puddles, and updates on her AP Latin exam and impending driver’s license test. She was everything you’d expect from a brainy teen who also happened to run abnormally fast.

Mary Cain, now 25, was the next big thing for U.S. track and field. Spectators were drawn to her talent, as well as her exuberance. But when her talent outgrew what her Bronxville, New York, high school could support, it got serious. Alberto Salazar—the Nike Oregon Project coach who had watched her set an American high-school record in the 1500 meters (4:11:01) at the junior world championships in Barcelona—came calling, interested in guiding the career of the promising prep star, the way he had done with another famous phenom named Galen Rupp.

Salazar started coaching Cain remotely during her junior year in high school. Before graduation, she ran her lifetime bests (including 1:59:51 for 800 meters and 4:04.62 for 1500 meters) and became the youngest American athlete to ever compete at the world championships. She gave up her NCAA eligibility to sign a lucrative contract with Nike at 17 years old. Then she moved across the country to Portland, Oregon, in a female body not yet fully developed, to join one of the most revered pro training groups in the world, led by Salazar with Nike’s backing.

But by 2015, at age 19, Cain’s star had faded. She chalked her lackluster racing up to “growing pains” and told the media she hoped they’d pass soon. What she didn’t say out loud at the time: she was cutting herself, suffering depression and suicidal thoughts, amenorrhea and other symptoms of relative energy deficiency in sport(RED-S). Years later, in a 2019 New York Times op-ed, she alleged that during the time she lived in Portland, Salazar regularly weighed her in front of teammates, withheld food, and berated her because he thought her breasts and bottom had become too big.

“For a very long time there was this stunting of myself. I’d always been that person who would say, ‘Hey, you’re doing something wrong. I don’t want to be a part of that; I’m going to speak up,’” Cain says. “But I think when you’re not able to understand the experience you’re going through and there’s no understanding that it’s abuse, you self-blame during it. That personality that would step up and make the world better wasn’t there for a few years.”

Cain chose to publicly share her experience after reading an unrelated U.S. Anti-Doping report which ultimately found Salazar guilty of violating anti-doping policies. He was banned by USADA for four years (until October 2023) as a result.

“It suddenly made me realize I’m not crazy. This wasn’t just me being weak. This wasn’t me being over-dramatic,” Cain says, two years to the day since the New York Times piece was published, during an interview in her Upper West Side apartment in New York. “This wasn’t just me.”

During those subsequent two years, several former Oregon Project athletes have corroborated Cain’s story and have also come forward (publicly and privately) with their own allegations of abuse. The Oregon Project shuttered in 2019 and Salazar is no longer under a Nike coaching contract. Cain, who left the team officially in 2016, filed a $20-million lawsuit in October 2021 against Nike and Salazar for long-term and permanent injuries suffered, as well as an eating disorder, major depressive disorder, and post-traumatic stress.

The U.S. Center for SafeSport, charged with investigating abuse in Olympic sports, has permanently banned Salazar for sexual misconduct. In response to Cain’s allegations, Salazar has denied wrongdoing, but issued a statement in 2019 saying, in part, that he did not know that discussing weight in elite sport was abusive. “I may have made comments that were callous or insensitive over the course of years of helping my athletes through hard training,” he wrote.

But it wasn’t insensitivity that has led Cain to find her calling. It’s the desire to help make sports a more supportive, safer place for the generations coming after her.

“We have to identify the people who are problems. Screw winning, screw your history with the team, screw your relationships,” Cain says. “If somebody is a problem, we have to get them out.”

“We have to identify the people who are problems. Screw winning, screw your history with the team, screw your relationships,” Cain says. “If somebody is a problem, we have to get them out.”

Making the Team

On a November Friday afternoon, during New York City Marathon weekend, Cain curled up on her gray couch in the apartment she shares with her boyfriend, Jake Kaufman. The couple bought the place during the pandemic, just a little more than a block from Central Park where their rescue pup, Nala, gets plenty of exercise alongside her humans.

Inside the door a pile of running shoes, all brands (except one, noticeably absent), is stacked against the exposed brick wall and spilled into the Manhattan-sized kitchen.

Cain works all three of her jobs from the fourth-floor walkup. She’s employed full-time as a community manager at Tracksmith, helping coordinate events and activities for the apparel brand in New York. She’s a coach at New York Road Runners. And her newest endeavor, launched in June 2021, is founder and CEO of Atalanta NYC, a nonprofit organization that employs professional female runners who help create and execute youth mentoring programs while pursuing their running careers.

Cain acknowledges that holding down three jobs is unsustainable while trying to get back into her own training, rehabbing some chronic injuries that have required surgery on her hips.

“We always talk about the fact that there’s periodization in your life,” Cain says. “For right now, at my age, and for how the world has been in the last year and a half, and because my training’s in the place that it’s in, I could take on more. But it means working really long days and multitasking a lot.”

Atalanta is backed by sponsors like Tracksmith, Nuun, and AirBnb, as well as private donations. It’s also supported by a well-connected board of directors, including former NYRR CEO Mary Wittenberg; Olympian, entrepreneur, and maternal health advocate Allyson Felix; and Evan Roth, founder of a wealth management firm. Its mission addresses many of the issues that led to Cain’s experiences as a young runner. The pro athletes, who are provided coaching, go through a rigorous and lengthy interviewing process to work as salaried employees, providing them more stability than a traditional sponsorship, as well as career development for after they’re finished competing. The youth mentoring component exposes girls in underserved communities to the benefits of movement and exercise.

“I’ve always found one of the biggest problems within the world of sport is that people don’t learn how to be healthy in sport until they’ve been very unhealthy and then have a major intervention,” Cain says. “We’re really trying to get in before and help introduce to kids how to create a healthy environment.”

So far, two athletes have joined the team—Jamie Morrissey, a middle distance graduate of the University of Michigan, and Aoibhe Richardson, an Irish runner who competed at the University of Portland. They are coached alongside Cain, by Jon Green, who also coaches 2021 Olympic marathon bronze medalist Molly Seidel.

Morrissey, who trained with the New Jersey-New York Track Club before joining Atalanta, was attracted to the larger purpose of the organization and its location in the city, she says.

“Mary’s obviously been through an incredible amount. To come out on the other side fighting for not only herself and her career, but many others also, I knew it was something I wanted to be a part of,” she says. “And the city gives me energy. It feeds me. I’ve always thought it was electrifying and inspiring and motivating.”

As more athletes are added to the roster, Atalanta isn’t necessarily looking for the fastest PRs or the most athletic potential. It’s far more important to Cain that the pro runners have passion for the nonprofit work that they’re hired to do.

“Highlighting Aoibhe, for example. She had reached out and was immediately like, ‘My long-term career goal has been to create a space within a U.S. city that gives free resources to people; where we can teach them how to cook or do exercise classes or provide a health clinic,’” Cain says. “She understood the goals. A lot of it is chatting through the fact that they’ll be expected to do community service work. There are hours outside of running where they’re expected to perform, but in a different way.”

Richardson, who has a master’s degree in public health, discovered the opportunity the day that Cain launched it—she sent a message on Instagram and asked how to apply.

“I felt like somebody had created my dream job and had written it down,” she says. “I felt like I had something to offer outside of my running. I still wanted to have something else to devote my time to, but in a way where I could have the flexibility and support to train.”

Using Power for Good

Cain doesn’t take her position within the sport lightly. She recognizes that she’s been given a spotlight that others who have lived through similar experiences have not.

“I’m a white blonde girl who grew up in a privileged family. I did that New York Times piece and I had millions of people listen and watch. I’ve already achieved a certain level of athletic performance that makes people recognize who I am,” she says. “That power is a privilege and that power is a responsibility. I have a platform, for right or for wrong or for in between, and I’m going to keep running with it.”

Since 2019, Cain’s story has stoked a broader conversation about the systemic failures of youth sports, particularly when it comes to girls, who drop out at a faster rate than boys in their teen years, mostly due to body image issues, perceived lack of skill, and feeling unwelcome. In track and field specifically, more athletes are recognizing abusive coaching practices, calling out strategies like public weigh-ins or body fat tests used in some NCAA programs without any accompanying education about nutrition, fueling, and body composition.

Cain hears from athletes regularly seeking advice on what to do and tries her best to respond to all of them.

“I hope that the more people step up, the more it will be listened to,” she says. “And when somebody is not listened to, it doesn’t mean they shouldn’t step up. People who have done it always know that whether or not it creates change, you just live a little lighter.”

Since her time at the Oregon Project, running hasn’t come back together the way that many had hoped for Cain. She’s focused on recovering from the eating disorder, stress fractures, and hip surgery. Over the past six years, she’s also dealt with another mysterious injury that makes her lose control of her right leg while she’s running. Over the summer she finally decided to take the time to figure out why. Doctors now think that an injury from years ago was misdiagnosed and mistreated by suggesting more strength training—they think it’s led to long-standing piriformis syndrome. It’s caused overcompensation on her right leg, where she has a bursa on her knee, resulting in instability.

“The truth is that this whole experience has just made me realize that I’m OK without running,” Cain says. “I think as runners, we’re so often taught that being a little banged up is OK. But it reached a point where I couldn’t really walk without feeling it. And I don’t, long term, want to have more health issues than I probably already developed. From a running perspective, I don’t really care anymore how it goes.”

As her coach, Green says wants running to play whatever role is best for Cain. He recalls when they first met, at the 2014 junior world championships, where Cain won the 3,000 meters.

“She’s an extremely good competitor. If she’s ever back on the track racing hard and going after titles, I would fully support that,” he says. “But if changing the sport is the most interesting thing to her, we know that there are phases to life and I’m here to support and help her do that.”

That girl holding court in the mixed zone in 2012 with Puddles the stuffed duck may never reach the athletic achievements that once seemed all but assured in her youth. She’s at peace with that—and has just as much of a desire to disrupt the system as she once did to win world championships.

“If tomorrow I win the Olympic gold, that will never be the fairy tale for me. That will never be the thing that heals the wrongs and makes everything right,” she says. “The truth is, no matter what I do in sports at this point, I’ve done the big thing already. And that’s standing up for myself, that’s standing up for other people, and that’s trying to create change.” —Erin Strout

Section divider

Mary Wacera Ngugi: Speaking Out About Domestic Violence

Sometimes it takes a tragedy. It shouldn’t have to, of course, but history has so often shown that meaningful change only occurs when society gets sufficiently angry about an injustice.

In October 2021, Mary Ngugi was on her way back to Kenya following a third-place finish at the Boston Marathon when her world was turned upside down. On a layover in Doha, Qatar, a friend asked her if she had heard the news.

“What?” she asked back.

“Agnes is dead.”

A month earlier, Agnes Tirop had broken the world 10K record on the road, clocking 30:01 at a race in Germany. But on 13 October, the 25-year-old was found stabbed to death at her home in Iten, Kenya. Tirop’s husband, Ibrahim Rotich, fled the town and was arrested the following night near Mombasa, arraigned on suspicion of murder. Local police said a confession letter was found at the couple’s home, allegedly written by him.

Among the outpouring of grief that followed, there was also rage. Female athletes in Kenya took to social media to vent about gender-based violence. Ngugi was among them, but as she came to terms with Tirop’s death, she decided it couldn’t stop there. The 32-year-old had long wanted to make a difference for her countrywomen, but she never quite knew how. “After Agnes, I said, ‘This is it.’”

She and Tirop knew each other but they weren’t close. Tirop was primarily a track runner who was based in Iten, Ngugi a road runner who lives about 150 miles away in Nyahururu. The two exchanged greetings when they crossed paths, aware and respectful of each other’s achievements.

In the days after Tirop’s death, Ngugi had dozens of conversations with athletes in Kenya and abroad, which resulted in her creating the Women’s Athletic Alliance. On its website, its stated mission is to “provide essential assistance for athletes suffering from domestic abuse, whilst offering mentorship and guidance to up and coming female athletes.”

Domestic violence is an issue everywhere, but Ngugi believes it’s especially prevalent in Kenya. “It’s something that happens almost every day,” she says. “It’s not just athletes, it’s everywhere. When you see how women are treated here, even in public, it’s not the same. It’s completely different.”

Ngugi knows how deep the inequality runs, though she counts herself lucky to have parents who treated her just the same as her brothers. She grew up in Kikuyu, outside Nairobi, and first tried competitive running at the age of 16. Back then, going to races on weekends was a nice alternative to farm work, and her talent quickly showed despite her doing no training.

At 17, she left home to join a running camp and though her parents supported the idea, her uncles were against it, telling her father not to let her go.

“The more we celebrate women, the more we give them confidence so they believe in themselves. When someone starts believing in themselves, it’s hard for someone to control them.”

She went anyway, developing into one of the world’s most promising distance runners in her late teens and early 20s. After taking a couple of years out to become a mother, she returned to running in 2012 and focused mainly on the roads thereafter, netting podium finishes at some of the world’s most prestigious races.

When she looks at the landscape for female athletes in Kenya today, she sees pitfalls at every turn, many of them due to men who enter women’s lives early in their careers with promises of financial assistance.

“That’s how you get into this, how they start controlling you,” she says. “Because these girls are young they start brainwashing them and when you start performing, they make it [so] your self-esteem is too low [to walk away]. There’s been cases of coaches sleeping with the girls and threatening them: ‘If you leave this camp, I will do this to you.’”

With the Women’s Athletic Alliance, Ngugi plans to visit schools and training camps, warning girls of the red flags that could signal toxic relationships. She also wants to empower them, giving them the confidence and skillset to make their own decisions about their careers and finances.

“These men have made them believe they can’t do it by themselves,” she says.

Another goal is to tell stories about female athletes from East Africa, amplifying their voices to the world. “The more we celebrate women, the more we give them confidence so they believe in themselves,” she says. “When someone starts believing in themselves, it’s hard for someone to control them.”

Ngugi received hundreds of messages of support from around the world after starting the initiative, but the depth of the issue was highlighted by the pockets of criticism, with one man telling her to retire and another arguing that supporting a woman financially makes her his property. After going back and forth on that subject, Ngugi soon followed a friend’s advice to ignore him.

Then there was the silence of male Kenyan athletes, which persisted as so many of their female counterparts voiced their anger about gender-based violence. “Everybody was talking about Agnes but [the men] were silent,” says Ngugi. “They all knew her, they had been to the Olympics with her. I’d love to see more men, especially the athletes in Kenya, talk about this but they’re not, which makes me mad. They feel we are attacking them, but we are not.”

As she looks to the future, Ngugi has many goals. As an athlete, she wants to win a Marathon Major, break 2:20, and compete at the 2024 Olympics in Paris.

“It sounds like those goals are big but I know I can do it,” she says. “Nothing is impossible if you work hard and believe in yourself.”

That same philosophy underpins her mission outside of running. Now that she’s started a movement, where does she hope to see it end? “More equality,” she says. “I’d like these women to feel we are equal, that the guy doesn’t make me feel like I’m less of a human, or that we cannot be heard.”

And if Ngugi achieves her goal, the tragic end to Agnes Tirop’s life could ultimately signal a new beginning for her countrywomen.

“Yes, we are mad about what happened but this is not just about her,” she says. “Tirop is gone, she will never come back, and [now] it’s to prevent that happening to other girls.” —Cathal Dennehy

Section divider

Stephanie Case: An Advocate for Women’s Rights, On and Off the Trail

The month prior to her first attempt at the 450 kilometer, unmarked Tor De Glaciers race in Valle d’Aosta, Italy, Stephanie Case wasn’t focused on her training. Instead, she paused in the midst of runs, frantically emailing and taking trailside calls to coordinate chaotic evacuation efforts from Afghanistan for team members of her nonprofit, Free to Run.

Since 2014, Free to Run has been Case’s passion project. When she’s not running and training for ultras, or mired in her work as a human rights analyst for the United Nations, she pours her energy into the nonprofit, which develops female leaders in areas of conflict—specifically Afghanistan and Iraq—through outdoor sport and adventure. Though their mission remains, the Taliban takeover of the Afghanistan government in the summer of 2021 made it far more important to focus on safety and security.

Case is not one to balk from a challenge. She has lived and worked in war zones and refugee camps around the world, which makes her well-adapted to ultra running (she can survive long periods with very little water and poor sleeping conditions) and exceptionally empathetic to the circumstances that women in in conflict zones endure. She has sought out some of the world’s hardest trail races over the past 15 years, including Racing the Planet stage events in Vietnam, Namibia, Australia, Nepal, and Mongolia; and the grueling maze of Tennessee’s Barkley Marathons, arguably the toughest 100-mile race in the U.S. She’s had iconic top-10 finishes in long ultras, notably the 330-kilometer Tor de Géants in Italy, which she’s repeated four times since 2015, and the 450-kilometer Tor de Glaciers as the first female and third finisher overall.

As the Taliban took control of Afghanistan and eventually the capital, Kabul, Case travelled to the country to help her team during the time she set aside to prep for Tor de Glaciers. She found herself burning and cementing documents in concrete to hide the identities of those who had been involved with the organization. Overnight the girls went from being able to run a marathon outside to being unable to get an education and being forced to stay indoors out of fear.

Case and her team evacuated the staff members of Free to Run, though many people connected to the organization still remain in Afghanistan. It’s currently too complicated to continue sports programs and community outreach to help women and girls to reclaim public space there, but Free to Run is strengthening their programs in Iraq and is looking to expand to other geographic regions in 2022. Case still believes they can creatively engage with women in Afghanistan, and she knows it’s critical.

“When women are not physically seen, when they are invisible, it becomes much easier for those in power to forget that they exist and have equal rights as the men in society,” she says.

Despite the emotionally stressful weeks leading up to Tor de Glaciers, Case still raced. “I wanted to toe the line out of respect for all of the women Free to Run had worked with over the years and what we had fought for: to ensure that women had a place in these male-dominated spaces.”

With only three women registered, Case was determined to prove that women belong in extreme ultra races. She managed to finish in just over 155 hours with only 4 to 5 hours of sleep. Each step of the way she was spurred by thoughts of the women in Afghanistan whose rights to run, and to participate equally in society, had just been extinguished.

“Women need to be seen—and heard—both on and off the trail,” she says. But she cautions that those who are excluded shouldn’t be responsible for making themselves included. Instead, she says, it’s the duty of event organizers, sports brands, and sports associations to address inequality and minimize barriers of entry for ultra running.

And she’s taken those steps beyond her own participation in races to elevate the visibility of women in sports and society. In 2021 she served on the Hardrock 100’s diversity committee to help increase women’s participation in the race, and in 2022 she will be a member of The North Face’s Explore Fund Council, where she’ll help develop scalable solutions to improve access to outdoor adventure. Plus she’s producing and starring in a film (out this spring) about herself and two women from Afghanistan who are pushing the boundaries of gender equality through running. —Brooke Warren

Section divider

Gabriela DeBues-Stafford: Increasing LGBTQ+ Visibility on the Biggest Stages

If you don’t know Canadian middle-distance runner Gabriela DeBues-Stafford by name, then you might recognize her by her hair.

She was the athlete racing with a rainbow-colored pixie cut to a fifth-place finish in the Olympic 1,500-meter final in Tokyo this summer. The hair color, originally dyed for Pride Month in June, became DeBues-Stafford’s small way to subvert the Olympics’ Rule 50, which bans all forms of demonstration or protest at the Games.

“I wanted to have a visual marker of representation,” she told Women’s Running over the phone from her home base in Portland, Oregon.

“It was a way of me saying something without worrying about the ramifications of Rule 50, which is the ban on protests, which is a silly rule. A lot of times with queer people, unless their partner is right there on the field of play, unless you know their backstory, it’s not necessarily visible… I was surprised how many people reached out to me and how many people it really resonated with.

“I think representation is really powerful.”

As a bisexual woman married to a man, DeBues-Stafford (who goes by “G” to friends and family) knows it’s easy for people to assume that she is heterosexual. That’s why she’s made a concerted effort to do things like dye her hair all the colors of the rainbow before competing on the sport’s biggest stage, and use her social media platform to shout-out the LGBTQ+ community.

“I think it’s important to increase the visibility in the sporting community of queer people,” she says. “That’s why I talk so much about it, because a lot of people would just assume that I’m straight and I think it’s important to talk about representation and make sport feel welcoming to the queer community. I’m a member of the community and I also am an ally because I’m not trans myself, so I try to amplify the experiences of trans people in sport, so my followers can be exposed to a more diverse array of life experiences because I feel like exposure is the first step… people need to diversify the content they consume and that’s a huge piece toward eliminating prejudices and in the end, oppression.”

The two-time Olympian’s profile is only growing after finishing in the top six of the 1,500 meters in two consecutive global championships.

Not that it’s been easy. In fact, this past year may have been the most challenging of her career.

In the midst of the global Covid-19 pandemic, DeBues-Stafford decided to leave her training group in Glasgow, Scotland with Laura Muir (1,500 meter Olympic silver medalist in Tokyo) to join the Bowerman Track Club in Portland. Due to border closures, she was unable to secure a visa to move to the United States until last September, and in the meantime, she had a Graves’ Disease relapse. She had managed the autoimmune disorder since 2013, but tried to wean herself off the medication at the beginning of the pandemic.

Graves’ Disease causes hyperthyroidism, or an overactive thyroid. Symptoms can include weight loss, anxiety, insomnia, digestion problems, and increase in heart arrhythmias, all of which DeBues-Stafford suffered from.

“When your metabolism is overactive, you lose muscle first so you’re extremely weak,” she says. “Being in the weight room and doing core was really a struggle. I had no strength at all.”

By the time she finally moved to Portland last September, she was back on medication but once her thyroid was at a normal level, she had to get back in shape. She says it took until around February of 2021, after BTC’s first altitude camp, to feel fit again.

But it’s another thing altogether to get the mind right for competition.

DeBues-Stafford says she has long suffered from general anxiety, and the nearly two-year layoff from racing messed with her mentality heading into the Olympic year.

“Sometimes with racing, if you stay away from it for too long, and you have a tendency toward race anxiety, it can feel like you take several steps backwards in terms of your progress toward being less anxious,” she says of the long layoff from racing. “It was really hard for me to get back into it.”

“I definitely have a general pattern of anxiety that, when you’re in a race situation, becomes exacerbated. I’ve struggled with race anxiety specifically, my whole life, and it definitely got worse after my mom died.”

When she was a teenager, DeBues-Stafford’s mother passed away after a two-year battle with leukemia. She cites therapy as an important resource to help her through that familial trauma as well as her general anxiety, which can be intensified by Graves’ Disease.

“The biggest strategy I used in 2021 [was] learning to trust my body,” she says. “That was my mantra for the whole year. The trust in myself and my body, especially after my relapse from Graves, because sometimes your mind is the primary thing creating the anxiety, creating doubts. Learning to be more in myself and less in my head, so when I’m feeling tired, I check in—how does your body actually feel? And, usually, your body feels actually good and ready for the challenge, so I learned how to feel grounded in myself, which is helpful.”

Somehow, she was able to bottle up all those feelings and perform her best during the Olympic Games.

“The whole year, I was trying to conquer some inner demons and I really feel that things just came together perfectly at the Olympics,” she says. “I reached this level of focus and clarity that was really incredible and I just enjoyed every second of my Olympics experience.

“It is very overwhelming when you feel adrenaline. I think with the anxiety piece, it’s framing that—do you think about those symptoms as positive or negative? I feel like for a long time leading up to the Olympics, I felt really focused on getting a medal and I didn’t want to lose the opportunity to get a medal, so that was very much, to me, a threat kind of response, where you feel like you have something to lose. And then at some point very close to the Olympics, I flipped the narrative in my head of you have nothing to lose and everything to gain. Letting go of, ‘I might not get a medal’ but I know that I’m going to run a race that I’m proud of.”

DeBues-Stafford had the unique opportunity to share the Tokyo Olympics experience with her younger sister, Lucia, who also represented Canada in the 1,500 meters. It was her first Olympic team. She set a personal best of 4:02.12 in the semi-finals, the fastest woman in history not to advance to the Olympic final—and G got to watch it from the finish line, right after her own semi-final.

In an Olympics without spectators, it was doubly special to share the moment with a family member.

“Her eyes were just lit up when she saw her time, 4:02, it was another massive PB for her,” she says. “It was fun to watch her run her best on the biggest stage of the year.”

Though Lucia (“Lu” to friends and family) didn’t make the final, she was able to be there for G. “How do you feel?” DeBues-Stafford remembers her sister asking her before the most important race of her life.

“I remember saying to Lucia, ‘I’m really, really nervous, but I know I’m going to run a race that I’m proud of and that’s good enough for me.’”

And now, three months later, DeBues-Stafford confirms that’s true. After a year of challenges, she won her first round race at the Olympics, ran 3:58 twice in 48 hours and finished fifth in the entire world.

The best part? DeBues-Stafford is only 26, and there’s four more years of consecutive global championships to shoot for that medal.

“2021 was an incredibly tough year for a lot of reasons, so I’m excited to be a little more established, more settled, have less change going on, and see what I can do with a year of stability under my belt.” —Johanna Gretschel

Section divider

Alysia Montaño: On Making Motherhood Habitable for All

Talk to Alysia Montaño, Olympic runner and founder of the nonprofit &Mother, about mothering, working, and how she “does it all” for long enough, and she’ll likely tell you about the beginnings of life.

See, when life on Earth began, there was very little oxygen; very few microbes could survive in the conditions. Then, something revolutionary happened: Microbes began living inside other microbes (forming what eventually became known as mitochondria, the powerhouse of a cell); and, because of mutually beneficial relationships, cells began living together (evolving to create what would be the first animals). Together, the world evolved.

Today, there tends to be a more singular idea, Montaño says, of how things have to be in order for one being (usually a cisgender, white male) to survive, and everything else around that one being lives in harsher conditions. “But in a beautiful world with so many different beings, we all need each other to survive,” she says.

And “doing it all?” It can feel like the only option moms are left with, she says. “It’s the air we breathe, but in a lot of ways, it’s toxic.” Last year, Montaño’s &Mother made strides in helping to clear the way for moms in sports, including running. The group worked with mom-focused activewear company Cadenshae to provide athletes breastfeeding-friendly uniforms, important in a world where women’s uniforms are “usually just less,” she says. &Mother also provided financial support for Olympian and Olympic hopeful mothers because, as Montaño puts it, “it’s one thing when you’ve already made the Olympic team, but how do we give moms the opportunity to try?”

This year, Montaño’s goals are loftier and include “thinking through different ways to make partnerships that are more than just a brand’s logo all over an athlete.” Take &Mother’s latest project with women’s running brand Oiselle: The two have pushed for sports sponsors to place protective language for pregnant people and mothers in contracts, something Montaño calls “a very basic ask.” After all, no one should be dropped from a sponsorship, as Montaño was from Nike, for becoming a mother.

Montaño is quick to point out that visibility during motherhood (such as breastfeeding-friendly uniforms) matters, but that a quieter side of the equation is equally as important, too. “I understand the women who do not want to be visible in the workplace, the women who do not want to be undermined,” she says. “Placing language within our policies and contractual agreements tells an athlete: If this is something that becomes a part of your life, you don’t need to worry about it, you don’t need to think about it, you’re protected.”

Imagining that is enough to make any mother breathe just a little bit easier.

“It’s how we’re able to make this world habitable, not just for one lifeform,” Montaño says. “Because I don’t want to do it all by myself. I don’t.” —Cassie Shortsleeve

Section divider

Francine Niyonsaba: Big Setbacks Fuel Her Even Bigger Comebacks

After Francine Niyonsaba, 28, won the 5,000-meter Diamond League final in September, she sent a message to the world on Instagram. “They tried to stop me. Tried to end my dreams. But how could I allow them to snatch my dreams away?” she wrote. “So I worked hard. Resisted those forces who tried to stop me. And here I am!”

Niyonsaba, who competes for Burundi, was the 800-meter silver medalist at the 2016 Rio Games. But since then, she had to make a difficult decision: either move up to the 5,000 and 10,000 meters or take measures to lower her naturally occurring testosterone levels.

As an athlete who has a condition called DSD (Difference in Sex Development), in which hormones, genes, and reproductive organs can present female and male characteristics, World Athletics policies mandate that she take hormone-suppressing drugs in order to contest events from 400 meters to the mile.

“For me, it’s about discrimination,” Niyonsaba said during an interview with the Olympic Channel, later adding, “For sure I didn’t choose to be born like this. What am I? I am created by God, so if somebody has more questions about it maybe [they] can ask God. I love myself. I will still be Francine. I will not change.”

After her private medical records were leaked, Niyonsaba said publicly in 2019 she has hyperandrogenism, which means her body produces more testosterone than women without the condition. She’s turned all the challenges she’s faced into additional fuel for her competitive fire, qualifying for the 2021 Olympics in the 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters.

In the qualifying round of the 5K, officials disqualified her for lane infringement—something she didn’t remember doing nor did many spectators see happen. It felt, again, like she was targeted.

“But I am not devastated. Because nothing could stop me. The more one tries to stop me, the stronger my comeback,” Niyonsaba said afterward. And she did come back, placing fifth in the 10,000 meters, setting a national record in 30:41.93, and vowing to compete again at the 2024 Paris Games.

Other DSD athletes, like 2016 Olympic 800-meter gold medalist Caster Semenya of South Africa, were unable to qualify for Tokyo in the longer distances. Margaret Wambui of Kenya, who had won 800-meter bronze in 2016, stopped competing altogether. But Niyonsaba insisted on looking forward and excelling in the events she was, by the rules, allowed to race (the research that World Athletics used to form its policy has since been corrected, noting that the results were not “confirmatory evidence” and exploratory in nature).

In 2021, she went on to set a 2,000-meter world record in 5:21.56. She won the Prefontaine Classic 2-Mile in 9:00.75 and set a 5,000-meter personal best in 14:25.34. “I did what I had to do,” Niyonsaba said after that Diamond League win, joking that if World Athletics tries to impose more restrictions on the events in which she’s allowed to compete, she’ll simply move to the pole vault or the high jump. “My perseverance is my answer to those who want to stop me,” she says. —E.S.

Section divider

Raven Saunders: Standing Up for the Disregarded

At the Tokyo Olympics, shot putter Raven Saunders wore a Hulk mask and her hair colored purple and green. She danced. She joked around. She also won a silver medal. Her experience in Tokyo marked a turning point, she says. “It was finally a time where I felt comfortable being myself, being open to myself, and really getting a chance to show the world who I was as a person,” Saunders says.

Saunders also competed at the 2016 Rio Olympics, but that experience was different. There, “I was trying to soak up as much information as possible” and learn from teammates, she says. “Seeing how they handled themselves and how comfortable they were being themselves . . . gave me that confidence.”

On the podium at Tokyo, after Saunders received her medal and the ceremony ended, she raised her arms above her head in an X. She said later that the X represents “the intersection of where all people who are oppressed meet.”

“I feel like, in society, a lot of people who deal with things or who are overlooked—they constantly feel disregarded. And for me, being a person who is Black and gay, and also who struggles with mental health, I feel like—especially these past couple of years, especially in America, but even more so all around the world—they’ve been very big topics of discussion,” she says.

She wanted people to know that even if they feel overlooked, they can still do great things. “Growing up, there weren’t too many people that I saw that looked like me or represented so many different things that I felt like I connected to,” she says. “That X was for anyone who can relate, or anyone who supports anyone who relates or anyone who has a family member that can relate, because at the end of the day, a lot of us really just need support in our corners.”

The International Olympic Committee launched an investigation into whether Saunders had violated its rules against demonstration, but it suspended the investigation. “For me, I always said, when I got to a position of being able to use my platform for something good, there was nothing or no one that was going to stand in my way of doing that.”

Saunders has talked openly about her struggles with mental health, including coming close to suicide in 2018. Since then, she has been more in tune with herself, including “being more honest with myself, really trying to understand myself more and being more compassionate with myself,” she says. Checking in with her therapist, meditating, and doing yoga have also helped maintain her mental health, she says.

Saunders changed the way she approaches getting through rough spots. She sees life as a cycle that often involves a challenge coming before a success. “A challenge before every breakthrough—that’s how life always has happened for me,” she says. “You have to keep pushing, and if you keep pushing, the success is going to come. But it was during that time, where I almost gave up in the midst of it, where I really learned that.”

While many Olympic medalists keep their medals locked away somewhere, Saunders typically carries hers around with her. That way, if she meets someone and gets to talking with them, she can let them see it and touch it. “I do it because you never know who your story can inspire,” she says.

Conversations matter to Saunders, among strangers and among friends. You may not know what your friends are going through unless you take the time to try to understand one another, she says. She remembers what it felt like to be outed as a kid, and now she leans on friends who support her. For example, she says, “I have friends who will stand up for me when people misgender me.”

In 2022, Saunders is looking forward to competing at the first world championships to be held on U.S. soil, as well as to getting into motivational speaking. “I really just try to spread a message of love and support and letting people be themselves,” she says. “You don’t have to completely understand it. You don’t have to completely love it. But just let them be them. Have some regard for one another.” —Allison Torres Burtka

Section divider

Molly Seidel: Proving Performance and Fun Can Coincide

Molly Seidel flew to the Olympics in Japan last summer with a degree of self-doubt. True, she’d run so well in her 26.2-mile debut she earned a spot on Team USA. Eight months later, she ran more than two minutes faster to place sixth at the London Marathon.

Still, she felt like “a little bit of a mess-up, still figuring it out.” Did she truly belong there? Could she compete at that level?

But alongside her imposter syndrome, she packed googly eyes, which she and her coach Jon Green stuck to doors and other hotel fixtures. Keeping the mood light has been key to her success, she says. Jokes remind her that even on the hardest days, she has a chance to do what she loves.

With positivity powering her, she proved herself on the world stage—persevering on a hard, hot day in the streets of Sapporo to win a bronze medal in the Olympic Marathon.

On the plane home, the hardware heavy in her pocket, Seidel contemplated the heft of what she’d done. “When I saw Deena Kastor win bronze in 2004, it was truthfully such a seminal moment in my life, really inspiring me to become a runner and want to do the marathon,” she says. “I hope there’s somebody out there that, watching this happen will inspire them to do something great.”

She’s secured her status as a marathon superstar, and membership to a select sisterhood that includes Kastor and 1984 Olympic marathon gold medalist Joan Benoit Samuelson. The shift to role-model status has felt strange, but Seidel indeed hears regularly from fans who’ve adopted her trademark “full send” approach.

She and Green first started using the phrase, derived from an internet-famous snowmobiler, in her buildup to the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials. Running her first marathon there was, in her words, “a ridiculous idea.” But the lack of expectations proved liberating—and her aggressive racing style, triumphant.

“Our whole attitude was, hold nothing back, go for it and just see where you come out,” she says. “It’s been fun to see people in various spheres take that whole idea of, I’m just gonna throw all my expectations out the window and go for something.”

Winning does come with a new set of pressures, something Samuelson discussed openly with her. The responsibility of inspiring a nation isn’t one Seidel takes lightly. Still, she’s determined to continue infusing it with fun and authenticity.

She’s always up for a goofy or unusual challenge, be it the slowest mile possible or a Turkey Trot in costume, especially for a good cause. The weekend after the Olympics, she started at the back of the pack of the Falmouth Road Race in Massachusetts. For each runner she passed, race organizers donated $1 to Tommy’s Place, a children’s cancer organization. By the end, with matching donations, she raised nearly $40,000.

“I hope people are able to see hey, even an Olympic medalist is having fun with this. I can too,” she says. Taking the sport too seriously in college nearly ruined it for her, negatively impacting her mental and physical health. Now, she hopes to show how staying in touch with her silly side leads to sustainable success.

If anyone had lingering questions about whether good vibes and fast times go hand in hand, Seidel dispatched them at the New York City Marathon last November. There, she placed fourth and first American in a course-record, personal best 2:24:42. Afterward, she talked about the ups and downs of her training and the race—but also her plans for a victory celebration. “Oh my God, I hope there’s a beer waiting for me at the hotel,” she said.

This year, Seidel has her sights firmly set on the marathon at the world championships in Eugene, Oregon, on July 18. It’s a date she’s had circled on the calendar for years—the chance to compete for a world title, on home soil. “There’s just something categorically different when you line up in a Team USA singlet and race for the country,” she says.

At 27, she likely still has years of competitive running in front of her, but she’s also thinking ahead. Alongside her training, she’s earning her MBA. “I realize I can’t run forever,” she says, and the degree will set her up to continue working to help athletes afterward.

One big, serious issue she wants to help solve: the enormous gap from running collegiately to making a living as a pro runner. “It’s really difficult, and a lot of people fall through the cracks,” she says. She’s already serving on councils in the sport’s governing body, USATF. With Olympic medalist next to her name, it’s a little easier to get her voice heard.

Even after such an epic year, Seidel still struggles with self-confidence. In those moments, she reminds herself of the lessons she hopes to share—racing hard is a joy, setbacks aren’t failures, and even pro athletes can relax with a cold one. “At the end of the day, I am living my dream,” she says. “And I feel strongly about finding a way to keep impacting the sport in a positive way.” —Cindy Kuzma

Section divider

Athing Mu: Making the Most of the Gifts of the Present

For Athing Mu, life after Olympic gold has pretty much returned to normal. She’s back in College Station taking sophomore courses at Texas A&M, attending track practice with the Aggies as their newest volunteer assistant coach.

She might get recognized a bit more around campus and the grocery store, but even that’s nothing new for the 5’10” star, who was a standout in New Jersey track circles long before her incredible Olympic summer in Tokyo, where she won gold medals in the 800 meters and 4 x 400-meter relay.

It wasn’t so long ago that a stranger at the grocery store actually changed her perspective on the sport—and, you could even say, her life.

“I remember I stopped at the store and one woman came up to me and said, ‘Oh, my gosh, you’re a really good athlete. I just want you to know, it doesn’t matter what age you are, you can do it now, no matter where you’re at or what you’re up against.’ She basically said, ‘your time is now,’ and that’s where I got that statement from,” Mu says of her oft-repeated mantra. “That changed my mindset because I was letting things go away, not in the worst way ever because I still competed well, but I realize now that that mindset I had a couple years back definitely played a role in how those years went versus how this past year went for me.”

Mu, who stormed to an American record of 1:55.21 in Tokyo (and later lowered her mark to 1:55.04 at the Prefontaine Classic), says she hasn’t always been the self-assured teenager who wore a red barrette spelling “CONFIDENT” in the Olympic final. When she first started rising to the top of the sport as a high schooler, she was quick to temper expectations.

“‘I’m only 16, I have 10-plus more years to accomplish this goal,’” she remembers thinking. “Rather than looking at it like, ‘I can accomplish this right now if I put my mind to it and I want to do it.’”

Mu graduated high school in 2020 during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and headed to Texas A&M to train under legendary sprint coach Pat Henry. The break from competition and adjustment to the collegiate ranks changed her perspective on the sport, and her role in it.

“I was kind of going through it,” she says of life before the pandemic. “Debating, deciding whether or not track and field was fun for me… After coming back to it, I regained that love and [realized] ‘Wow, this is what I was supposed to be doing that entire time, why am I even questioning it?’”

Before their first meet, Henry told the team, “We don’t know if this is going to be our first or our last meet this year, so don’t let the day get away.”

Mu took that sentiment to heart. So did the rest of the Aggie women, who banded together to earn team runner-up honors at the NCAA Championships for both indoor and outdoor track.

“I think I used that toward every single race I had this entire season, which helped me progress and that’s where the confidence came in,” she says. “Seeing all the success I had one meet at a time, going out and running my best and not worrying about anything else, just trying to get the best out of the day that I could.”

That mindset drove her to break six collegiate records, capture three individual NCAA Championship titles, break the American outdoor record, dominate the U.S. Olympic Trials and the Olympic Games 800-meter finals, and cap her Games with the fastest split of the 4 x 400-meter relay: an incredible 48.32.

She says the relay was her favorite moment of the Olympics, especially because she got to run anchor.

“That was the best thing that ever happened,” she says. “We had the greatest athletes in the world, in history. To be in that and also to be the anchor… Them choosing me to be in that position was like, ‘Wow, that’s great.’ And I also ran a fast time, so overall it was great. I appreciated that the most out of everything and being part of history tied the whole knot.”

Mu focused on the 400 meters during her collegiate season, and likely would have contended for individual gold had she contested the event at the Olympics.

Next Olympics, she may just run the 400 and 800 meters. Only one person has ever won both events at the Olympics: Cuba’s Alberto Juantorena in 1976.

“We were talking about this earlier in the year, my coach and I, running the 4-8 double,” she told media after her historic gold, the second in history for an American woman. “Most definitely. We’re going to put my name on the list of the two people that have accomplished that. Because I want to do it.”

She also wasn’t shy about declaring her intent to break the world record for 800 meters one day, which was set at 1:53.28 in 1983 by Jarmila Kratochvílová of Czechoslovakia.

But these are long-term goals for Mu. For now, the 19-year-old is focused on defending her global title on home turf next year at the world championships.

“For it to be the world champs next year and for it to be in Eugene on U.S. soil with everyone actually able to be there, it should be a great experience for all of us,” she said. —J.G.

Section divider

Sydney McLaughlin: Big Changes are Paying Off

It’s easy to forget that Sydney McLaughlin is just 22 years old. The New Jersey native conquered the Tokyo Olympic Games like a true veteran, and as a two-time Olympian after making her first U.S. team at age 16, perhaps she is.

Whenever she hits the track, magic usually follows—especially if her chief rival, fellow American Dalilah Muhammad, is in the race, too.

“Iron sharpening iron,” McLaughlin has said of Muhammad. “Every time we step on the track, it’s always something fast.”

The duo have pushed each other to new heights in the 400-meter hurdles for the past few years. But this summer, McLaughlin took things to a new level: she became the first woman to break 52 seconds in the event when she won the U.S. Olympic Trials, then lowered her world record to an astounding 51.46 to win the Olympic final in Tokyo. Muhammad led the early stages of the race and nearly looked like she’d defend her title, but McLaughlin was too strong in the closing meters and successfully captured her first global title with a perfectly executed race.

“It feels surreal,” McLaughlin says now of the moment she’s dreamed about since she was 8 years old. “My team and I were truly in such an amazing place, and God worked everything out according to His plan. It was truly beautiful.”

The newly minted Olympic champion came back to close out the final day of competition by leading off Team USA’s gold medal-winning 4 x 400-meter relay. The moment was made even more special for the fact that her training partner, Allyson Felix, was part of the quartet as well, along with Muhammad and 800-meter specialist Athing Mu.

During the pandemic year, McLaughlin made a big change by switching coaches from Joanna Hayes, a USC assistant coach and 2004 Olympic gold medalist in the 100-meter hurdles, to the legendary Bobby Kersee, who has guided the careers of his wife, Jackie Joyner-Kersee; the late Florence Griffith-Joyner; and, of course, Felix, who closed out her fifth and final Olympic Games in Tokyo as the most decorated U.S. track and field Olympian of all-time and the most decorated woman in Olympic track and field history with 11 medals.

“One thing I have learned from Allyson over this year is to trust the process, and Bobby’s timing,” McLaughlin wrote in an email to Women’s Running. “He will always make sure we are ready to go when it matters. We definitely sync up during workouts sometimes. It’s fun having someone so talented pushing me to be better.”

It’s clear that Kersee knows how to guide big stars, and though it was a leap of faith to swap coaches during a year of overwhelming uncertainty, McLaughlin says the move helped her grow as a person on and off the track.

“The biggest challenge this year I faced was just having faith in a new program during such a big year. It honestly couldn’t have turned out any better though,” she says. “This year, one thing I learned about myself is how beneficial it is for me to step out of my comfort zone. In all facets of life.”

Kersee is McLaughlin’s fourth coach in five years, after graduating from high school in 2017 and spending one incredibly successful year in the NCAA at the University of Kentucky under coach Edrick Floreal (now at Texas) before turning professional in 2018.

McLaughlin would often see Kersee’s group at the UCLA track and made the change after consulting with him on her hurdling technique.

“Training under Bobby has been amazing,” she says. “He is such a seasoned coach, as well as an amazing person. Our bond has grown stronger over the course of this year, and I look forward to seeing where our journey takes us.”

The sky is the limit for McLaughlin, who will be in her athletic prime with global championships scheduled for the next four consecutive years. years. The world championships in Eugene will be a welcome change after Tokyo’s spectator-less arenas, and, of course, her residence of Los Angeles will play host to the Olympic Games in 2028.

“Not being able to go over and hug my fiancé and parents were part of the dream that got put on hold this year,” she says of winning in Tokyo. “Honestly, for me, the best part is being able to share these moments with my coach, family, and friends.”

Will she go even faster in the 400-meter hurdles? Will she revisit her untapped potential in the flat 400 meters? Or the 100-meter hurdles? There are many questions ahead for one of the United States’ brightest young stars, but, for now, she is mum on the details of goals beyond this standout year—and has a wedding to plan.

“This year I just want to continue to grow into all God calls me to be,” she says. “On and off the track.” —J.G.

Section divider

Dinée Dorame: Telling Runners’ Stories

When Dinée Dorame was growing up, her family would run together at night, and her dad was her cross-country coach. Both running and storytelling have long been part of who she is as a Navajo woman. She brought the two together when she started the Grounded Podcast, which explores running, culture, land, and community—and the spaces where they overlap.

“I’ve always lived at the intersection of athletics and culture,” Dorame says. She has a background in journalism and enjoys talking to people as a way to understand them better, in part because she didn’t feel like she fit in when she left New Mexico for college on the East Coast. “I think my way of building community was by talking to my peers, especially other Native students, and learning more about what keeps them literally grounded.”

The Grounded Podcast got off the ground in early 2021, thanks to support from the Tracksmith Fellowship. In nearly a year of hosting the podcast, Dorame has interviewed dozens of runners at all levels of running, both Native and non-Native. She tries to avoid over-planning these conversations or steering them too much, preferring to let the conversation flow between her and the guest.

When her guests are Native, Dorame wants to “show other people that Native people are multi-dimensional, and we’re not just here to educate others or teach only about our cultures,” she says. She wants to get into interests, talents, and skills beyond that.

Dorame wants the podcast to represent people as authentically as possible. “I believe representation matters, but I also believe that if systems don’t change behind it, you’re just placing people in a spotlight with no support,” she says. She aims to make sure Grounded guests “feel supported, and they feel like they’re a part of a conversation with me, and they’re not there for me to extract information from them.”

“I’ve experienced a lot of really positive feedback, especially from Native people, and that kind of keeps me going,” Dorame says. A couple of Native studies professors have asked to use her show in their classes, because the podcast has covered important events in Native history, in the context of running and sports, she says.

The podcast allows Dorame to facilitate the storytelling of other Native runners in a way that’s widely accessible, she says. “That’s important to me, to make sure that my family can hear it and my community can hear it.”

In her day job, Dorame is the associate director of College Horizons, a national college access program for Native American, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian high school students and families. This work and the podcast complement each other: Dorame often talks to guests about their experience as collegiate student-athletes. For example, when Navajo pro runner Alvina Begay was on the podcast, “she explained to me what it was like to be a Native runner on her team in college and how, in many ways, that made it difficult to connect with other Native students on campus. But she found her community in her own way,” Dorame says. The podcast often delves into the theme of finding community wherever you go.

Since Dorame started Grounded, she has been injured and unable to run, and she has missed the connection that running provided. But the podcast has helped to fill that void, with all the time she has spent talking with people about running. “The podcast has now become this thing I do to connect to place and people and culture,” she says. “I am grateful that I have this new conversation space and platform, because I think it’s helped me understand that the sport will always be there for me in many different forms.”

Dorame is looking forward to expanding the show onto other platforms such as YouTube and TikTok, and trying a live format. Grounded has featured runners ranging from Billy Mills to Latoya Shauntay Snell to Rebecca Mehra, and in future episodes, Dorame hopes to talk to athletes in other sports, as well as artists and creators, about what keeps them grounded. —A.T.B.

Section divider

Alison Mariella Désir: Pushing the Running Industry to Be Better

The running community has gone through an awakening of sorts in the past year or two. “Some people are finally coming to recognize that these false notions that everyone has equal access to our sport, that our sport is super accessible and super welcoming, that all you need are running shoes—there’s been a realization that that’s not the case, depending upon your race and other intersectional identities,” says Alison Mariella Désir. She has helped push the running industry toward this recognition in several areas, including as Oiselle’s director of sports advocacy and as co-chair of the Running Industry Diversity Coalition, and through writing her forthcoming book, The Unbearable Whiteness of Running.

Désir has seen signs of progress. “At least for Black and other people of color, we can finally feel like we can speak the same language with some folks in the industry,” who previously lacked awareness of how people of color experienced running and the industry, says Désir, who is also the founder of Harlem Run.

Brands have also improved representation in marketing, but that’s the low-hanging fruit, Désir says. Sometimes campaigns feature Black people but lack diversity behind the scenes, for example: “There’s no Black person doing hair and makeup, or there’s no Black person behind the camera or coming up with the storyline,” she says.

At Oiselle, Désir’s work includes building community, making the Haute Volée elite team more diverse, and expanding the charitable Bras for Girls program. Désir has her own Oiselle collection that launched recently, built around the idea that “comfort and style belong in all places, and outdated ideas of professionalism are incompatible with our life,” she says.

The Unbearable Whiteness of Running, due out next fall, shows how history is still alive in the present, Désir says. The U.S. moved from slavery to segregation, and then to de facto segregation with housing policies and other lingering inequities. “All of those things are descendants of slavery and ways in which this initial idea of racial hierarchy has persisted. I wanted this book to show how running developed within this environment, so there’s no way that running or anything else could be untouched by it.”

The book also chronicles Désir’s personal journey “navigating white spaces my whole life, and coming into the running industry and realizing that it was another white space to navigate,” she says. “And yet at the same time, running grounded me and has given me my mental health, my community, my partner, my son—it has given me so much. It’s grappling with that sort of cognitive dissonance and then what it means to be active in changing the running industry for the better.” —A.T.B.

Section divider

Erin Azar: The Unlikely Social Media Star

In a landscape dominated by hyper-filtered images and rail-thin fitness influencers, 38 year-old social media sensation Erin Azar stands out.

Her self-deprecating “outfit of the day” photos and humorous running videos discussing everything from the realities of getting your period while running to stashing water bottles in the cornfields surrounding her Midwestern home have amassed a huge following: over 60,000 Instagram followers and 25 million TikTok views as well as features in the New York Times and on The Today Show.

It all started in 2019, when the mother of three was in a “postpartum haze” after the birth of her last child and decided to do something she hadn’t done in a long time: lace up for a run.

“I remember sitting in my living room one day and thinking I needed to be by myself and do some kind of exercise, and it was a nice day out,” says Azar.

So she grabbed some old sneakers and set out on the winding country roads surrounding her home in Berks County, Pennsylvania.

“I had on baggy clothes, my shoes had holes in them, and I didn’t even make it a mile,” she says. “But for the first time in a long time, I felt my mind ease a little bit, so I knew it was something I needed to do for my health.”

To hold herself accountable and make the new habit stick, she decided to run a mile every day for thirty days and posted videos to her “Mrs. Space Cadet” YouTube and TikTok channels, hoping to connect with other struggling, beginner runners.

“I was desperately searching for someone else that ran, who wasn’t super skinny, who could tell me what to wear to not have my thighs chafe,” she says with a laugh.

“I thought I’d make a friend or two,” she continues.

So she was shocked when her videos—”good morning, here’s another installment of a slightly overweight person who drinks too much beer trying to train for a marathon,” she jokes in one TikTok—started racking up millions of views, an online community that buoyed her through months of pandemic isolation and race cancellations.

“I was finally getting to the point where I thought I was good enough to meet up to run with another person, and then everything shut down,” she explains.

“But people kept commenting [on my videos] with things like ‘you inspired me to start running or do my first 5k,’ and I realized everyone’s life is imperfect, and we’re all in this together.”

Azar leans into that imperfectness, whether it’s sharing the struggles of running on two hours of sleep, showing off sweat stains on her rotation of colorful shirts, or confessing to a lack of motivation for long runs.

“I’m not surprised when I see articles about how social media is bad for you, because seeing only super skinny runners posting super fast times is what kept me from running for so long,” she says of her relatable content and frank delivery. “If I had seen someone out there that looked like me, I’d have started running a lot sooner.”

And Azar didn’t just start running: she decided to train for her first marathon.

“Why start small,” she jokes.

Disappointed when her planned New Jersey Marathon was canceled last October, she jumped at the chance to run the TCS New York City Marathon, raising over $66,000 for The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research in honor of her father, who has the disease.

With millions of fans ranging from other frazzled moms and new runners to professional athletes like Dana Giordano—a “TikTok mutual”—Azar says she is “blown away” by the attention, and lives for her followers encouraging each other and “vibing” in her comments.

“No matter what level you’re at, we all have crap running days, and it’s important to be the person out there who isn’t afraid that sometimes this sucks and everything hurts,” she continues. “But at the same time, it really blows my mind what happens when you consistently show up for yourself.”

While she’s mum about her specific race plans for 2022, she will continue to go big and keep it real.

“I want to do something in a really crazy location or that’s more challenging and forces me to up my training and overall health, that’s run to film and edit, so my audience can be excited to follow along,” she says. —Laura Scholz

Section divider

Mechelle Lewis Freeman & Jennifer Nash Forrester: Empowering New TrackGirlz

Imagine a middle-school girl who wants to run track but faces barriers. Perhaps her school lacks a team, and club membership fees—not to mention shoes—are too costly for her family. At a time of life when she most needs support, she’s shut out from the sport, and its benefits and opportunities.

Now, contemplate what her future might look like if, instead, she scored a brand-new pair of spikes and joined a club with funds for uniforms and travel. What if she also attended a camp—in person or virtually—with other young athletes, led by Olympic-caliber mentors and coaches? Then, scrolling her social media feed, she saw inspiring stories of women who look like her, achieving greatness both on the track and off it.

Welcome to the world of TrackGirlz, a fast-growing non-profit improving girls’ access to the life-changing possibilities of track and field.

Through grants, workshops, and storytelling, 2008 Olympian Mechelle Lewis Freeman and former University of Washington sprinter Jennifer Nash Forrester encourage and educate the next generation. At the same time, they’re shining light on the stories of athletes, present and past, who tend to be overlooked by the broader running community.

“We live in a world where women in track and field often don’t get credit for the impact we’ve given to sport and culture,” Freeman says. “The vision of the non-profit is really to expose and demonstrate that, while empowering girls.”

The idea for TrackGirlz came when, after competing in Beijing in the 4×100 meter relay, Freeman was working at a marketing agency. She asked why no track and field stars were among the athletes on the company’s roster. A colleague told her they were only relevant every four years, around the Olympics.

“I found that pretty shocking, to say the least,” Freeman says. After all, more middle- and high-school girls participate in track and field than any other sport. And she knew its icons—think Flo-Jo and Jackie Joyner-Kersee—inspired, motivated, and shaped popular culture.

So, Freeman went to work, trademarking the term TrackGirlz and starting an LLC. “I’ve been called a track girl since I was 14,” she says. “The community already existed; I just wanted to breathe life into it.” She began selling apparel—hoping to stake a claim for track style in the emerging athleisure industry—and organizing camps for young athletes.

Freeman found Forrester, a wellness coach and fitness professional, on Instagram and asked her to lead a track-inspired workout at an Arizona camp. The two became fast friends and trusted collaborators. When Freeman decided, in 2018, to convert TrackGirlz into a 501(c)3, Forrester signed on as co-director.

The focus on service was always there, Freeman says. Non-profit status meant they could seek grants, allow sponsors to write off donations, then pour those resources directly into local communities and young athletes.

The transition was already bearing fruit, and the pandemic provided an unanticipated boost. With other projects on pause, Freeman and Forrester devoted even more time to the organization. They booked virtual interviews with high-profile track girls—think Netflix chief marketing officer Bozoma Saint John and former Miss USA Cheslie Kryst, along with Olympic medalists, such as Dawn Harper Nelson and Tianna Bartoletta—and hosted Zoom workshops.

And when Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd’s murders sparked a conversation about racial justice both inside and outside the running community, even more people tuned in. “When attention came to minority organizations, we were ready for it, because we had been living and breathing this work,” Freeman says.

From 2020 to 2021, TrackGirlz’ social-media following grew by a factor of six, collaborations flourished (apparel brand JackRabbit, for instance, gave them $25,000 to redistribute in grants), and Freeman and Forrester committed even more boldly to their vision. “We’re definitely diving in headfirst and taking up space, unapologetically not asking for permission, saying yes to ourselves,” Forrester says.

Ambitious 2021 projects included a 100- and 200-meter street race for middle and high school girls in conjunction with the U.S. Olympic Trials; winners got free tickets to watch the elites compete. TrackGirlz also produced Tokyo Dreamz, a 15-minute documentary featuring shot putter and Olympic silver medalist Raven Saunders. And in May, they held a virtual discussion with members of the historic Tennessee State University women’s track team, the Tigerbelles.

Freeman also went back to the Olympics, this time as an assistant relays coach for USA Track & Field. TrackGirlz has also become a go-to source for news and context about competitors and events. So in between her duties as coach, Freeman was texting updates and photos back to her team stateside, “trying to win medals and be a media company,” she says.

Indeed, it’s a lot for a small team. But heading into a year in which eyes will once again be on the sport—with the World Championships on U.S. soil for the first time—Freeman and Forrester have no plans of scaling back. Rather, they hope to hire a director with non-profit experience to support them as they continue to proclaim track and field’s ongoing relevance.

“We want to continue to create that space where stories can be told and girls can have support,” Forrester says. “Things are changing. Women are really at the forefront. And it’s time everyone starts to recognize the potential that can happen through an organization like ours.” —C.K.