Products You May Like

Aside from powder skiing, most backcountry skiers can agree that there’s no surface more fun to ski than creamy spring corn. For many skiers, especially those who live in mountain ranges with continental snowpacks like the Rockies, spring is the time to get after big objectives. Once melt-freeze cycles have kicked off, persistent weak layers typically go dormant and are replaced by a solid, isothermal snowpack that can make for some incredible skiing.

IFMGA and Lead Exum Guide Brenton Reagan says that corn snow is elusive, but it can be some of his favorite turns of the season. “True corn skiing is skiing a perfect groomer, trustworthy, predictable, uniform,” he says. “That’s why people love it so much. It gives that effortless feeling that highlights the senses the same way powder skiing does.”

So, what exactly is corn snow? While you may have heard the term thrown around midwinter, Reagan emphasizes the fact that corn snow really only exists when the snowpack has undergone enough melt-freeze cycles to have turned snow into large-grained rounded crystals– essentially tiny pieces of ice bonded together when frozen. When freezing (overnight and early in the morning), it’s a firm, impenetrable surface, one that can hold your weight and is easy to travel on with crampons. Throughout the day, melting occurs, dissolving the bonds between grains and turning to slush.

Related: 6 tips for nailing soft spring turns at the resort

Hitting this snow before it turns to slush—when your skis penetrate only the top quarter inch of snow—are the hero conditions that spring skiing dreams are made of.

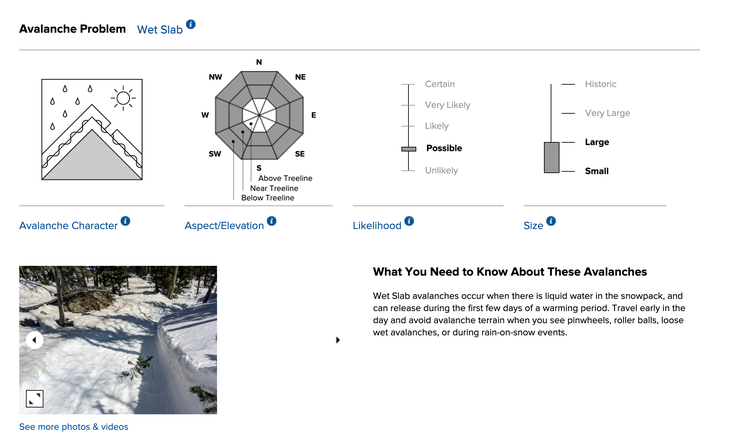

All that stands in the way of making those dreams reality is timing. If you ski too early, the snow surface is chattery at best, and slide-for-life conditions at worst. Too late, and you could encounter deep manky snow and wet slide conditions. Unlike the winter, where you can often rely on soft, cold snow all day long, corn skiing is only viable for a short window during the day, and it’s imperative to hit it right both for fun and safety.

Here, Reagan offers up a few tips to consider when planning a spring corn missions in the backcountry.

Study up on temperature profiles

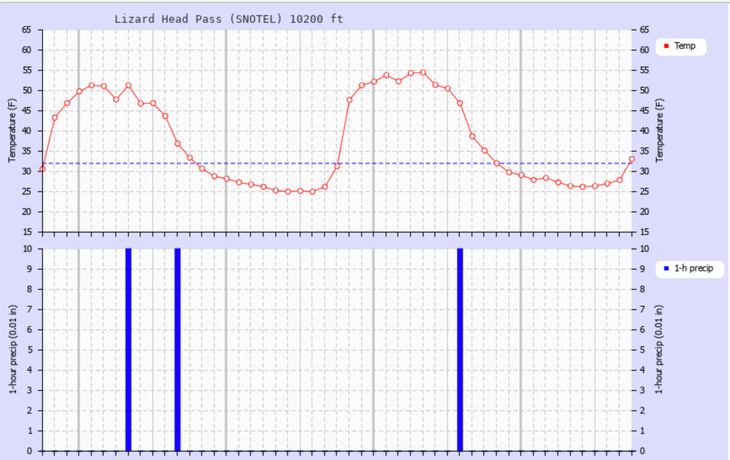

A proper melt-freeze cycle is crucial for a successful corn harvest. If it doesn’t fully freeze overnight, conditions won’t firm up enough for corn. Likewise, if temps aren’t going to warm up enough during the day, those bulletproof conditions won’t relent. “Checking temperatures is going to tell me how long I can travel in the mountains; what time I have to get up in the morning, when I want to ski, and when I want to be out of there,” says Reagan.

Ideally, you’ll have overnight temperatures below 30°F for 5-6 hours to ensure a solid freeze. Multiple hours in the 20s is even better. Depending on how warm it was the day before, a one or two-hour dip down to 31° or 32°F could be insufficient for a real freeze. Conversely, the warmer it’s going to get throughout the day, the earlier you’ll want to be done skiing. Subtle warming will be far more friendly to ski conditions than extreme temperature swings, which will shorten the window of skiable snow.

Check temperatures throughout your tour, since they may vary quite a bit from your high point to the trailhead. Reagan says that temperature is the best place to start because if temps don’t line up, it might be unsafe to go out into the backcountry altogether. “If it’s warm and cloudy all night, don’t even bother getting out of bed.”

Check your aspect and slope angle

Once you’ve determined that the terrain you’ll be traveling through is going to freeze, it’s time to consider the aspect you want to ski. In the northern hemisphere, east faces get sun first, then south, then west. Depending on how steep the terrain is and the time of year, north faces often remain shaded for most of the day. Because of that, if you’re going after an east face, you’ll want to be on it earlier than any other aspect.

Slope angle is easy to overlook, but actually plays a huge factor in how long your window to ski is. The steeper the slope, the shorter the window for perfect corn because the angle of the sun is hitting it more directly. A steep east face in the Tetons will go from rock hard to dangerous slush in as little as an hour, while some of the big, rolling peaks in Colorado deliver soft corn turns for hours on end.

Read more: How to use an avalanche report to plan your backcountry ski day

Consider your exit

Timing perfect snow on your line is one thing, but it’s important to consider the whole route, not just the epic couloir you’re hoping to nail. How exposed are you on the exit route? Often, if you’re timing your summit turns for perfect corn, you’ll be skiing mashed potatoes on the way out, which is fine as long as you’re prepared for that and off any avalanche-prone slopes. “You’d have to be a wizard to ski from the summit back to the car in perfect corn,” says Reagan. “At the end of the day it’s probably going to be manky, so I need to choose terrain on my egress that’s not going to avalanche on me.”

Take terrain features into consideration

When it comes to warming, dark rocks pick up far more heat than the reflective snow. Because of that, a walled-in couloir getting direct sun can warm much quicker than a wide-open slope. Take note of the terrain you’ll be traveling through and how that could potentially accelerate warming.

If you time it right, corn skiing can rival deep winter days, extending the stoke for skiing well into May and sometimes into June. It’s not easy to do, and if you want to nail it, Reagan admits “you need to be borderline obsessive about it.”

But when it’s on, there’s nothing else like harvesting spring corn in the backcountry.