Products You May Like

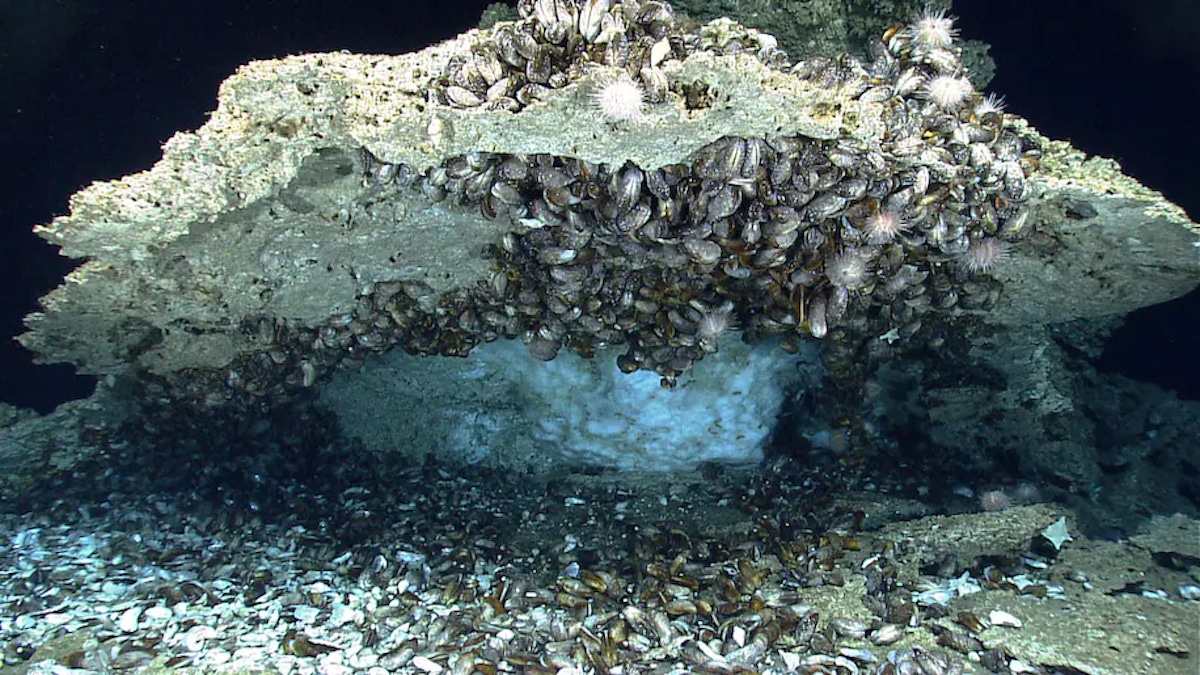

A methane hydrate. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Ocean Exploration and Research Program

Why you can trust us

Why you can trust us

Founded in 2005 as an Ohio-based environmental newspaper, EcoWatch is a digital platform dedicated to publishing quality, science-based content on environmental issues, causes, and solutions.

One of the biggest concerns about the climate crisis is that warming temperatures could trigger additional releases of greenhouse gas emissions that would in turn generate more warming. One example is the melting of the Arctic permafrost. Another is the release of methane from the world’s oceans.

Now, scientists have found evidence that this latter feedback loop has been triggered in the past. Research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Monday revealed a methane release that occurred when the tropical Atlantic warmed around 125,000 years ago.

“Our results highlight climatic feedback processes associated with the penultimate climate warming that can serve as a paleoanalog for modern ongoing warming,” the study authors wrote.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas that is more than 80 times stronger than carbon dioxide when first released, though it degrades more quickly, The Washington Post explained. Today, major sources of methane include leaks from fossil-fuel infrastructure, factory farming and landfills. However, one-sixth of the world’s methane currently lies at the bottom of the ocean, Inside Climate News explained. At the moment, it is frozen by a combination of low temperatures and high pressure in the form of methane hydrate or clathrates. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that hydrates hold more than 4,000 times the methane burned as natural gas in the U.S. in 2010.

The concern is what might happen if ocean temperatures heated up enough to release all that methane, though scientists have said it would likely be released slowly enough that the ocean would absorb most of it before it could heat the atmosphere, The Washington Post explained.

Still, the new research unveils the possibility that some of that undersea methane did make it to the atmosphere in the past. The study focuses on a period around 125,000 years ago called the Eemian Age. During that period, global temperatures were around one to two degrees Celsius warmer than they are today, according to Inside Climate News, and sea level was around 20 feet higher, according to The Washington Post.

The study authors focused on what happened during this time off the Gulf of Guinea in the tropical Atlantic by looking at sediment there, according to the paper, finding evidence of a feedback loop. First, meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet weakened the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Current (AMOC). This caused the waters in the middle of the ocean to warm by 6.8 degrees Celsius, enough to thaw the methane hydrates. That warming, study leader and University of California, Santa Barbara paleoclimatologist Syee Weldeab told The Washington Post, was stronger than previous models had suggested.

“And then, the release of methane is strong and persistent over a longer time, to make it basically noticeable through the sediment, through the water column, and potentially, to the atmosphere,” Weldeab added.

Other scientists familiar with the study said that the findings don’t mean the same thing would happen because of Arctic ice melt today or in the near future. And the difficulty of interpreting sediment data means it might not have happened in the past as the study authors described it.

“Conclusions from data like this are always provisional, [and] become stronger if they are confirmed in multiple proxies,” University of Chicago geoscientist David Archer told The Washington Post.

Weldeab also told Inside Climate News that many models of current global warming predict an uptick of one to three degrees Celsius, which would leave the sea-floor methane stable. But the example from the past is an important reminder that there are many interconnected threads keeping the climate stable, and untangling one can untangle more in unexpected ways.

“It’s not only the warming, right, but the feedback process, the loop process of warming,” Weldeab told Inside Climate News.

Subscribe to get exclusive updates in our daily newsletter!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from EcoWatch Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.