Products You May Like

Planning a thru-hike can be just as daunting as actually hiking a long distance trail. Fortunately, both tasks are best tackled the same way: one step at a time. To help you make your John Muir Trail dreams come true, we’ve put together a step-by-step guide to take you from daydreaming about hiking the JMT to actually doing it.

John Muir Trail Basics

The John Muir Trail is a 211-mile footpath that starts in Yosemite Valley and runs south along the crest of the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range to the top of Mount Whitney, the highest point in the lower 48 states. Interestingly, the trail’s namesake, John Muir, never actually hiked the JMT; the trail’s construction began in 1915, the year after his death. It was built atop a network of ancient footpaths laid down by the Paiute and other Indigenous people for thousands of years called Nüümü Poyo, or the People’s Paths.

California’s Sierra Nevada mountains are one of the world’s most beautiful and rugged mountain ranges, made up of glittering granite that has been uplifted by plate tectonics and sculpted by glaciers. The JMT crosses some of the Sierra’s highest and most remote terrain. For the majority of your trip, you’ll have no cell service and you’ll cross no roads. The trail crosses several wilderness areas and three national parks: Yosemite, Kings Canyon, and Sequoia.

Join our community for access to our free member resources!

Download our Handy Outdoor Packing Checklists and Trip Planning Guides

Trail Stats

- Total distance: 211 miles from Yosemite Valley to the top of Mount Whitney, plus 11 miles down to the Whitney Portal trailhead

- Days needed: 18-22

- Trailhead start: Happy Isles in Yosemite National Park (Southbound), Horseshoe Meadow or Cottonwood Lakes/Pass (Northbound)

- Best time to hike: July – September, depending on snowpack

- Total elevation gain/loss: 47,000 ft gain/38,000 ft loss (Southbound)

- Permits: Required and very competitive

- Difficulty: Strenuous and logistically challenging

- Dogs allowed: No

- Cell service: Rare

Best Time Of Year To Hike the JMT

The JMT is a high summer trail, and the best time to hike it is typically mid-July through early September to avoid prodigious snowfall and avalanches in the winter and dangerous creek crossings in the spring. However, the JMT hiking season is heavily influenced by the winter snowfall in the Eastern Sierra.

In low snow years, it may be possible to hike the JMT starting in June and into mid-October. But early and late season hikers should have significant snow travel experience and be prepared for sudden changes in weather.

In June, hikers may encounter snow on the high mountain passes, necessitating snow safety gear like microspikes and an ice ax, as well as strong navigational skills when the trail disappears under snow.

During the fleeting summer months (July and August), mosquitoes and biting flies can be legion, thanks to the abundant water found along the trail. Definitely bring a head net, bug spray, and a tent with mosquito netting.

On high snow years, creek crossings may remain dangerous throughout the summer. Trekking poles, sturdy hiking boots, and a partner can help make crossings safer. In September and October, hikers may encounter snowstorms and frigid overnight temperatures but will encounter fewer bugs.

How Long Does It Take To Hike The JMT?

With nonstop Ansel Adams-worthy views, plentiful swimming holes, and once-in-a-lifetime side trips around every corner, the JMT is an experience best savored. Under the load of a ~35-pound pack, with considerable elevation gain and loss, you’d be hard-pressed to rush through this trail anyway.

In general, backpackers can expect to cover around 10 miles a day so most people will hike the JMT’s 211 miles in 18 to 22 days. Of course, it’s possible to cover the distance much faster, but the better question to ask is: how long can I afford to spend on the JMT? If you’re going to go through the trouble of hiking one of the world’s greatest hiking trails, why not devote as much time as possible to exploring the route?

When I hiked the JMT NOBO in 2020, I took 27 days to hike over 300 miles. The extra miles came from the numerous side trips I took off the JMT corridor to explore the countless lake basins and summits that can only be accessed from the JMT. When BFT Founder Kristen hiked the JMT back in 2014, she took 22 days and hiked roughly 240 miles.

JMT Trail Difficulty

Mile for mile, the John Muir Trail is one of the most epic hiking trails on Earth. But you’ll be earning all those views with a lot of sweat and maybe a few tears (hopefully no blood!). The trail follows the crest of the Sierra Nevada mountains, rarely dipping below 10,000 feet of elevation.

To cross this soaring mountain range you’ll need to climb. Over the course of 211 miles, you’ll gain over 47,000 feet of elevation, including climbs over eight major mountain passes: Donohue, Silver, Selden, Muir, Mather, Pinchot, Glen, and Forester, the highest pass, at 13,153 feet. In between the passes you’ll be traversing across spectacular lake basins where you’re never far from water and where the best campsites are usually found.

Altitude sickness is a real possibility on the trail, but you can help mitigate its effects by training for your hike, staying well-hydrated and nourished, and giving your body time to adjust. By starting in Yosemite and hiking the trail south you’ll have several weeks to work your way up to the trail’s high point on top of Mount Whitney at 14,505 feet. This is the official end of the trail, but you’ll then need to descend 11 miles, down 6,600 feet to Whitney Portal to end your hike (making the grand total 222 miles, not counting side trips).

The numbers can be intimidating but the reality is the JMT is so spectacularly beautiful, so well trodden, marked, and maintained, with plentiful water and campsites that actually hiking the trail is a backpacker’s dream. With adequate planning, training, and preparation, you’ll be setting off for the greatest hike of your life.

Which Direction Should You Hike the JMT?

Traditionally, the JMT begins in Yosemite Valley, at the Happy Isles trailhead, and runs for 211 miles south to the grand finale on the summit of Mount Whitney.

The main advantage of going Southbound, or SOBO, is that you start at a lower elevation, which gives your legs and lungs time to adjust to hiking at altitude before you tackle the highest passes en route to Mount Whitney. Resupply logistics are also a little easier hiking SOBO, as you’ll be able to mail resupply boxes to Red’s Meadow and Muir Trail Ranch and deal with the trickier logistics of the more remote southern portion of the trail later in your trip. However, getting permits to go SOBO can be difficult. In fact, Yosemite wilderness permits are some of the most sought-after permits in the National Park system.

Around 20% of JMT thru-hikers elect to hike Northbound, or NOBO. However, getting a permit to start from Whitney Portal is also difficult, as you’re competing against people who want to hike Mount Whitney, the highest mountain in the lower 48. And you’ll have to tackle a huge 6,600 foot climb up Whitney at the start of your hike, as well as some of the highest passes in the first week.

Resupply options are also few and far between in the southern third of the trail, usually requiring significant side trips. You’ll have to figure out your resupply plan between Muir Trail Ranch and Mount Whitney whether you’re hiking NOBO or SOBO but it can feel easier to tackle this towards the end of your hike rather than at the beginning.

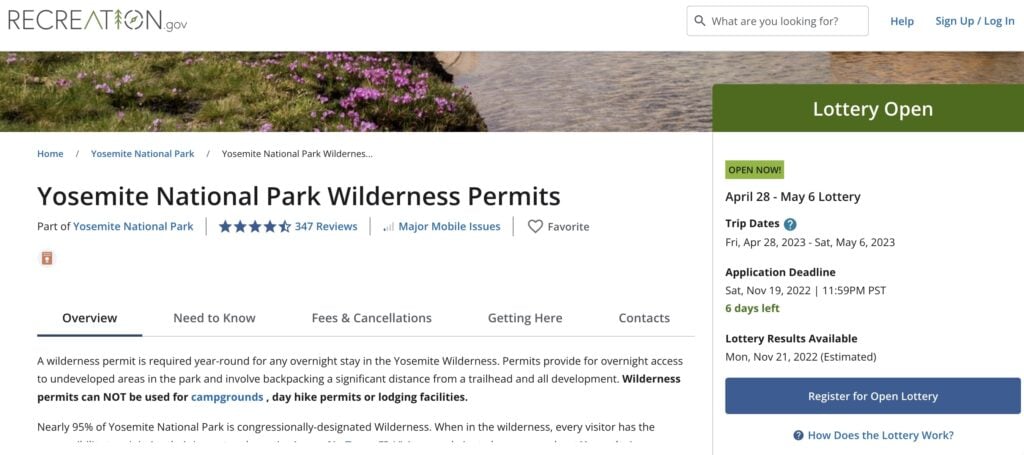

How To Get John Muir Trail Permits

Before you do anything else, you’ll need to surmount the single hardest obstacle in planning a JMT thru-hike: getting a permit. I won’t sugarcoat it: JMT permits are akin to Golden Tickets. According to the National Park Service, 97% of JMT permit applications are denied, but there are a few tips and tricks that can help increase your chances of getting a permit.

On a thru-hike of the JMT, you will pass through three National Parks and several different wilderness areas and National Forests. Fortunately, you only need one permit, which will cover your entire hike. It’s not actually a JMT permit; rather it’s based on your starting trailhead. So if you start your hike in Yosemite, you need a permit from Yosemite National Park. If you start in Inyo National Forest, you need a permit from Inyo National Forest.

When applying for a SOBO permit from Yosemite National Park, there are two main trailheads: Happy Isles and Lyell Canyon. When you apply for either of these permits, you’ll also need to select “Donohue Pass Eligible” so that you can exit Yosemite National Park over Donohue Pass to continue south on the JMT. Yosemite National Park only issues 45 wilderness permits for Donohue Pass per day. Of these, 20 are available for the Happy Isles to Past LYV (Donohue Pass eligible) trailhead and 25 are available for permits using the Lyell Canyon (Donohue Pass eligible) trailhead.

By far the most coveted permits are those issued by Yosemite National Park to start at the Happy Isles trailhead, as well as those issued by Inyo National Forest to start at the Whitney Portal trailhead. But while those are the traditional starting points for SOBO and NOBO hikes, respectively, they aren’t the only options.

On my 2020 NOBO trek, I started from the Horseshoe Meadow trailhead, 28 trail miles south of Mount Whitney, to avoid the competition at Whitney Portal.

For permit deadlines and more information on how to apply, check out our post on How To Apply for a Southbound JMT permit.

As annoying and discouraging as permits and trailhead quotas can be, they are necessary to protect the trail and the quality of the wilderness experience. If everybody who wanted to hike the JMT in July and August were allowed to go, the mountains would be overrun with people, and the trails, campsites, and water sources would be quickly degraded.

Do NOT be tempted to hike without a permit! The JMT crosses hundreds of miles of remote wilderness, but it’s actively patrolled by backcountry park rangers. I had my Inyo National Forest permit checked three times, once in Kings Canyon National Park and twice in Yosemite. I also met a group of four young hikers from Seattle who were ending their JMT hike early because they didn’t have a permit and got caught by a ranger and were facing steep fines if they continued. Flaunting permit rules can also get you banned from future permit lotteries.

How To Get To the JMT

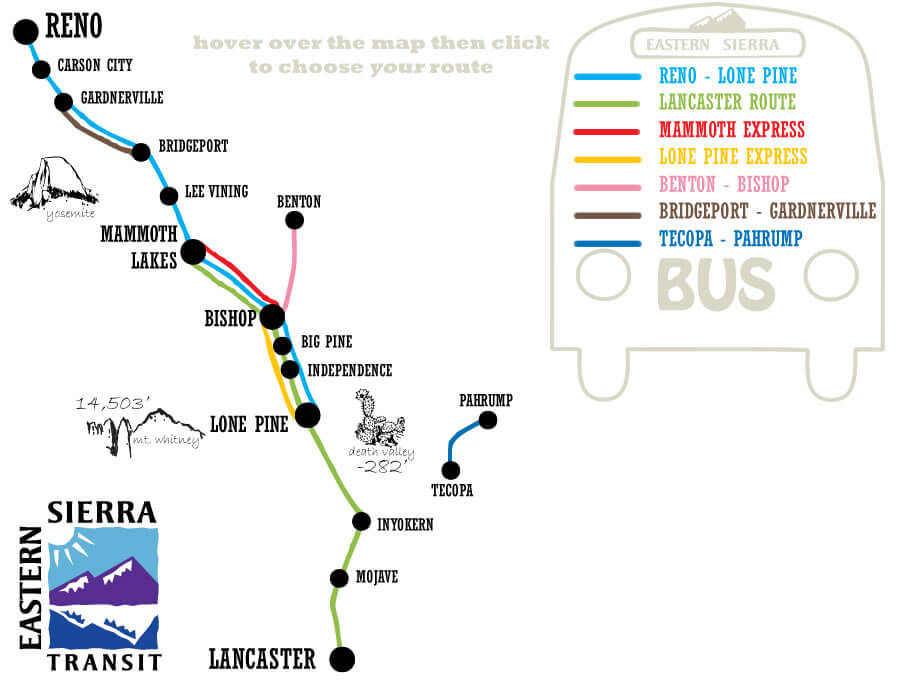

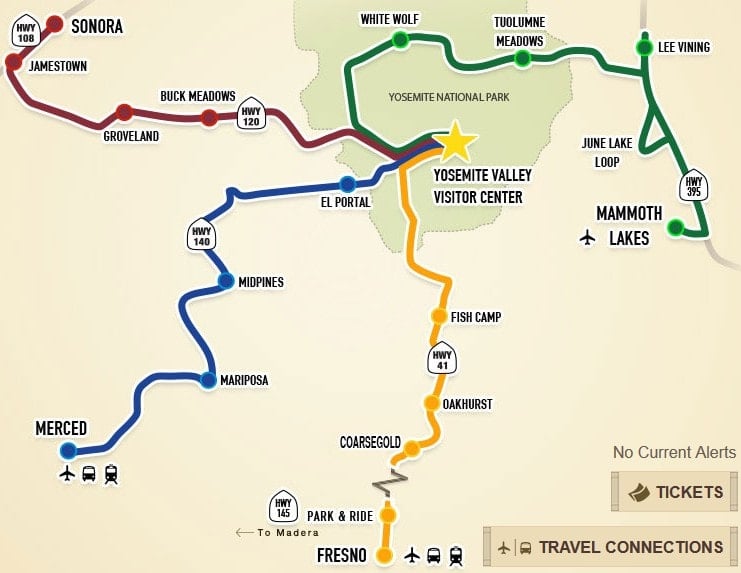

Whether you hike the JMT SOBO or NOBO, you’ll be ending your hike hundreds of miles from your starting point. There are a few ways to get to and from the starting and ending trailheads of your hike, depending on whether you have your own car or will be relying on rides or on public transportation.

If you have your own car, it’s best to park it at your ending trailhead and get a ride or take public transportation to the start of the hike. That way you can end triumphantly at your car and drive yourself to a victory meal and a hot shower. Most of the trailheads in the Sierra allow for long-term parking but check with the local ranger station and let them know your dates of travel.

If you plan on taking public transportation at the start or finish of your hike, keep in mind that the options are generally easier in Yosemite, which is serviced by YARTS: Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System. Scenic Highway 395, which runs along the eastern side of the Sierra, is serviced by Eastern Sierra Transit buses and the small towns along 395 are generally very adept at catering to hikers, with several private shuttle companies options based in Mammoth, Bishop, Independence, and Lone Pine.

Hitchhiking from the various trailheads into town is also common practice and you can usually get a ride with a fellow hiker or day tripper in exchange for tales of your epic adventure (and maybe a few bucks for gas). Not everybody is comfortable with this option, but if you trust your gut, hitchhiking can be a fun part of your hiking adventure.

For more info on which cities to fly into, a breakdown of the various public transportation options, as well as route and contact info for bus and shuttle companies, check out our post on John Muir Trail Transportation Guide and Planning Tips.

Planning Your JMT Itinerary

When you apply for your JMT permit, you will need to know your starting date, ending date, and where you plan to spend your first night on the JMT. Once you have your permit, it’s tempting to want to plan out where you’ll spend every night in between, but it’s also important to stay flexible. Once you’re on trail, a multitude of factors (weather, altitude gain, available campsites, fellow hikers) will affect how many miles you cover each day.

On average, most people will hike around 10 to 15 miles a day. The JMT is blessed with plentiful campsites and abundant water sources, so don’t stress too much about finding a campsite each night. Even if the tent sites within sight of the trail are all taken, you’re likely to find many more within a half mile of the trail.

Always follow Leave No Trace principles and select established campsites on durable surfaces. Never set your tent up on top of fragile vegetation – especially in the alpine zone – and don’t camp within 200 feet of water sources.

Hiking the JMT involves gaining and losing considerable elevation up and over numerous high-altitude passes. The best strategy for tackling these passes is to camp near the base the night before so you can hike the pass first thing in the morning when your legs are fresh and the weather is the most stable. Camping at or near the top of passes isn’t usually a great idea due to high winds, unpredictable weather, and frigid nighttime temperatures at altitude.

You’ll also need to plan out where you’ll pick up your resupply boxes along the way, which we’ll cover below.

If you’re curious about what a sample JMT itinerary looks like, check out Kristen’s 3 Week John Muir Trail Itinerary, where she highlights the best viewpoints, campsites, swimming holes, and more during her 22-day hike.

What To Eat on the John Muir Trail

On the JMT, you will spend around three weeks on trail, far from restaurants and grocery stores so you will need to pack or mail yourself all your meals for 20-plus days of strenuous hiking. You will likely be ravenously hungry on your hike, but of course, you can’t bring infinite food, as you will need to carry it on your back and fit it into an approved bear canister each night to keep critters out of your precious food stash.

For each day on the JMT, you’ll want to bring breakfast, lunch, and dinner, plus lots of snacks! There’s a lot of information online about the staggering amount of calories burned while backpacking (over 500 calories an hour!), but unless you’re really into calorie counting in your daily life, it’s not necessary to get too bogged down by numbers when planning a backpacking trip. As an easy rule of thumb, aim to bring around 2 to 2.5 pounds of food per person per day which should be around 3,000 to 4,000 calories per day.

When shopping for the JMT, seek out calorically dense foods that can be repackaged neatly into ziplock bags. You want the highest quantity of calories and nutrients in the smallest and lightest package to maximize the value of each food item. Don’t buy anything low calorie or low fat.

Also remember, you will have to carry your trash for at least a week so you don’t want foods that are messy or smelly.

Store-bought dehydrated meals have gotten increasingly better in terms of both taste and quality ingredients with several companies making organic meals that cater to an array of dietary restrictions. In the interest of saving space in your bear canister and cutting down on trash, you’ll need to repackage these meals into ziplocks. It’s cleaner and more efficient to reheat dehydrated meals in an insulated pot with an insulating cozy than in the foil bags.

Pro Tip: divide store-bought meals into multiple servings and add extra dehydrated veggies (these can be bought in bulk), a protein such as a tuna packet or salami, and an instant grain like couscous or rice to make an adequate portion. One of the easiest ways to add extra calories is to bring a plastic container of olive oil and add a tablespoon or two to each meal.

For more tips and recipes visit our John Muir Trail Food Shopping List and Best Lightweight Vegan Backpacking Meals.

How To Resupply on the John Muir Trail

One of the biggest logistical challenges of the JMT is figuring out how to resupply your food along the way. You’ll spend much of the trail’s 200-plus miles immersed in wilderness, far from grocery stores and restaurants so you’ll need to mail yourself several resupply packages along the way. The most common resupply spots on the JMT (listed SOBO) are:

- Red’s Meadow (mile 60.8)

- Vermillion Valley Report (mile 88.1 plus 12 mile side trip off JMT or ferry boat ride)

- Muir Trail Ranch (mile 106.1)

- Bishop Pass trailhead/ Bishop (mile 136.2 plus 23.6 mile round trip side trip off JMT)

- Onion Valley trailhead/ Independence (mile 180.3 plus 15 mile side trip off JMT)

Most JMT hikers will take advantage of the Red’s Meadow and Muir Trail Ranch reservices, as they are both located a short distance from the JMT. Both of these require mailing about a week’s worth of food in a box or 5-gallon bucket, at least two weeks before you begin your hike. Both Red’s Meadow and Muir Trail Ranch have very specific instructions for how to pack and mail your resupply on their respective websites and more info can be found in our blog post How To Resupply on the John Muir Trail.

You will likely also need to arrange a third resupply in the southern portion of the trail, as there are 117 miles of trail to hike between MTR and Whitney Portal. At an average backpacking pace of 10 miles a day, this section will take at least 11 days. Some people can hike fast enough and stretch their food supply to avoid this third resupply but this is not recommended as you definitely don’t want to feel rushed or low on calories towards the end of your hike.

The better plan is to arrange for a food drop at Onion Valley trailhead or one of the other side trails that branch off the JMT. The downside is that these will all require significant side trips. For example, Onion Valley is a 15-mile round trip detour, but it’s also spectacularly beautiful with many excellent camping options along the way. There are also a few backcountry outfitters who will meet you on the JMT with your resupply, carried in style by pack mule. These options tend to be expensive but can be made more reasonable by splitting the service with several other hikers.

For lots more tips, tricks, and info about strategizing, packing, and mailing your resupplies to the various resupply points on the JMT, read How To Resupply on the John Muir Trail and John Muir Trail Food Shopping List.

Bears & Food Storage

For many hikers, the possibility of encountering bears is one of the scariest parts of planning a JMT hike. But the reality is that with so many other people on trail, you’ll be lucky to spot a bear in its natural habitat. In general, bears and other wildlife prefer to avoid close contact with humans and the JMT is a veritable superhighway through the wilderness.

However, each year a few clever Sierra bears learn to associate people and campsites with food, usually when people are careless about leaving food unattended or unsecured in camps or cars. This can be very dangerous, especially for the bears. A fed bear is often tragically a dead bear.

To keep bears away from human food, all hikers on the John Muir Trail are required to carry an approved bear canister. These sturdy plastic or metal containers are the only proven way to keep bears from accessing food in the High Sierra, where bears are adept climbers and tall trees are rare.

You can buy your bear canister or rent one from ranger stations for a small fee. Ursacks and Opsacks are not acceptable alternatives on the JMT. Backcountry rangers will check that you have a canister when they check your permit.

While hiking, you can keep snacks accessible in pockets of your backpack but in camp, all food, trash, and scented items need to fit inside your canister, including toiletries like toothpaste and lotions. Keep a clean camp! Don’t leave food or scented items out if you’re not in the act of consuming them. At night, the locked canister should be placed at least 50 feet from your tent, in a location where it’s not easily kicked off a cliff or into a creek. Bear canisters are designed to be too bulky for bears to pick up or carry away but they will sometimes roll the canister around a bit.

If you do see a bear on trail, keep calm, speak to the bear so they can identify you as human and give them as much space as possible. Never approach or follow a bear or make it feel cornered. If a bear comes into your camp, chase it away by yelling and banging your pot! Get mad. Scold it like it’s a bad dog. Don’t let it think it’s welcome to explore your camp. If the bear doesn’t leave, or even if it does, consider moving to another location or teaming up with fellow campers. Black bears are not normally a threat to people, and are usually dissuaded by several people all yelling at the bear to go away.

What To Pack on the John Muir Trail

When it comes to packing for backpacking, less is more: the less weight you bring, the more you will enjoy your trip. There’s nothing worse than suffering under the weight of a too heavy backpack, especially on a multi week hike like the JMT.

Before my JMT thru-hike, my hiking partner and I sat down with all of our gear and a kitchen scale, weighed out everything, and entered it all into a spreadsheet. Seeing the numbers broken down by item really helped shave off a few pounds. I traded out my trusty (but heavy) Osprey pack for a much lighter Granite Gear Blaze 60 pack, lightening my load by nearly 2 pounds.

That might not sound like much, but when you’re carrying weight for over 300 miles, every ounce counts! By the time I hit the trail, I had whittled my base weight down to 22 pounds, not including food and water. So even fully stocked with 8 days of food, my longest food carry between resupplies, my pack still weighed under 40 pounds.

If you can afford to invest in some new gear, do your research and be very selective about what you buy. Gear technology and innovations have really accelerated in the last few years and there are lots of lightweight options for backpacking tents, sleeping bags, stoves, and clothing.

Everybody has their personal preferences when it comes to sleep systems, cooking systems and clothing systems. Unfortunately, the lightest gear is often expensive and not as durable as you might hope. For intensive use, such as on the JMT, it often makes sense to pick a slightly more rugged option so it’ll survive your trip and hopefully a few more!

The best advice is to test your gear and really get to know it before you set off on your JMT adventure. Plan to take at least one overnight shakedown hike ahead of your trip. If possible, take multiple shakedown trips! Ideally, over multiple nights! Keep notes about what you use and what you don’t use. You may be able to drop a few unnecessary items ahead of your JMT adventure. Remember less is more and every ounce counts!

For Kristen’s detailed packing and gear list, visit our Complete John Muir Trail Gear List and read Ultralight Backpacking Tips for advice on how to shed weight.

Where to Camp on the John Muir Trail

Hiking all 211 miles of John Muir Trail takes around 20 days, which means you’ll also get to spend around 20 nights sleeping under the stars. Campsites along the JMT are generally excellent and plentiful so don’t stress too much about finding a spot to sleep each night. Of course, some options are more spectacular than others so we’ve collected our favorite campsites into one post: 15 Best John Muir Trail Campsites.

So what makes a great campsite?

First, it should be a previously established tent site that is more than 100ft away from any water source. We’ll discuss more about Leave No Trace on the JMT in the following section.

Second, it should be flat. There’s nothing more annoying than rolling downhill all night.

Third, it should be quiet. With so many campsites in so much wilderness, you should not have to listen to somebody snoring in their tent a few yards away.

Fourth, it should be near water. On the JMT, this requirement is usually easy. The trail crosses countless lake basins and you’ll rarely be far from water for more than a mile or two. Even if there’s not a lake or creek right by your campsite, you’ll likely be able to fill up in the late afternoon before you strike camp. Just be sure to follow LNT principles and set your tent up at least 100ft away from water sources.

Beyond the basic requirements, the best campsites are the ones that afford spectacular views of sunsets, moonrises, the Milky Way, sunrises, or all of the above. But while we all love a wide-open vista, keep in mind that if it’s stormy, you’ll want some protection from the wind and lightning. The only thing worse than a tilted tent is having to listen to your tent flapping around you all night. Exponentially worse is worrying about your tent being struck by lightning! If storms are threatening, seek a low spot for your tent, perhaps in the trees, but always check for dead branches and debris that might fall onto your tent in a storm.

When looking for a campsite, keep in mind that while you can often spot tent sites along the trail, you might not have much privacy here as other hikers will be walking right by your tent. But if you explore a little off the trail, you’ll be sure to find many more site options a short distance away that will be much quieter. When exploring away from the trail, be sure to keep your bearings so you can find your way back!

With so many site options on the JMT, there’s no need to create new tent sites. See our next section on Leave No Trace for guidelines on how to enjoy the wilderness without marring the experience for others.

How To Leave No Trace on the John Muir Trail

You know that old saying, “take only photos, leave only footprints”? Well if at all possible, avoid even leaving footprints! Ideally, after you’ve hiked the John Muir Trail, there should be no sign that you were ever there. That’s the ethos encouraged by the seven core principles of Leave No Trace outdoor ethics:

- Plan ahead and prepare

- Camp on hard and durable surfaces

- Dispose of waste properly

- Leave what you find

- Minimize campfire impacts

- Respect wildlife

- Be considerate of other visitors

With so many people enjoying the Sierra’s pristine wilderness and untouched landscapes on the John Muir Trail, it’s important that everybody do their part to preserve this wilderness for future visitors. The JMT passes through high alpine environments, which are incredibly rugged but also incredibly delicate. A few LNT techniques to keep in mind when hiking the JMT:

- Always set your tent up on an existing tent site. There are many established campsites on the JMT – you should not create new sites or set your tent up on vegetation.

- Always camp at least 200 feet from water. Creeksides and lakeshores are easily eroded and often vegetated and you may be blocking wildlife’s access to water sources.

- Scatter dishwater. Also, do not dump food waste or food particles in creeks or lakes.

- Never use soap in creeks. You shouldn’t need soap on your hike, save the weight and leave it at home. A fingernail brush can do wonders for dirty hands, feet and lower legs, no soap needed.

- If you want to swim in the many alpine lakes on the JMT, avoid slathering on sunscreen or lotion before you jump in.

- Pack out all garbage, including toilet paper. Do not burn or bury anything. Used toilet paper can be bagged in dog waste bags (bring a roll, they are light and durable) and then double bagged in a ziplock bag. On Mount Whitney hikers are required to use wag bags for solid waste. You can pick up a wag bag at the Crabtree Meadows Ranger Station before you begin your climb up Whitney.

- On the rest of the JMT, pee at least 100 feet away from water sources, and step well away from the trail and campsites. To poop, walk at least 100 feet away from water sources, the trail and campsites, dig a hole 6 to 8 inches deep (carry a lightweight trowel for digging, sticks are not sufficient tools), and bury your waste, taking care to leave the surface unmarked as much as possible. Pack out all toilet paper.

- Do not build rock cairns or leave trail markers.

- Do not cache food anywhere on trail (this is not an appropriate way to resupply).

- All JMT hikers are required to carry and use an approved bear canister.

- Keep a clean camp. Store all food and scented items in your bear canister unless actively eating. Mice, skunks, and bears are all attracted to human food smells.

- Fires are only allowed in a few areas on the JMT but consider going fire-free on your trek to conserve limited wood resources and reduce the potential for forest fires. California is a tinder box!

Remember that Leave No Trace is not black and white but about making the best possible decision to minimize our impact in the specific environment and circumstances that we are in. Not a set of do’s and don’ts, but a set of guidelines to help us leave the places we visit as good or even better than we found them.

Additional JMT Resources, Maps, & Guidebooks

The John Muir Trail is a legendary route that has ferried people through the rugged heart of the Sierra for thousands of years (originally as the Nüümü Poyo). Much has been written about the JMT and the Sierra by many poets and adventurers from Muir himself into the modern day.

For a comprehensive reading list of all things JMT, check out our post on the Best John Muir Trail Maps, Books, Apps and Resources, from Muir’s classic Wilderness Essays to Elizabeth Wenk’s John Muir Trail Guidebook to the best paper maps and apps to help plot and track your route.

What else do you want to know about hiking the John Muir Trail? Do you have any additional John Muir Trail planning tips or advice? Let us know in the comments below!