Products You May Like

Young and cocky freeriders or backcountry newbies—that’s who’s most likely to get caught in an avalanche, right? Maybe not.

Avalanche victims are trending older—the median age in the 2020-2021 season increased to 44—and experts are scratching their heads as to why. Older and wiser may not be the key to staying alive in avalanche terrain after all.

Last fall, I sat alongside my fellow backcountry skiers at the Center for the Arts for the annual Wyoming Snow and Avalanche Workshop (WYSAW), a series of presentations from some of the country’s leading avalanche experts, scientists, guides, meteorologists, and educators. WYSAW is a great time to brush up on some of the terms and concepts that completely escape my mind during the long, snow-free days of summer, and there are always some interesting perspectives and topics brought to the table that leave me wondering as I head into the heart of the backcountry season.

Related: Backcountry basics they didn’t teach you in Avy 1

During Dr. Karl Birkeland’s presentation, where he talked about the deadly winter of 2020-’21, he presented a graph of the median age of avalanche victims in the entire U.S. Over the last decade it’s begun to trend older, a median age of 34 for the past 30 years, but last year’ s increase to 44 was a statistic that came as a surprise to industry professionals.

“The idea that we were going to have all these young, inexperienced people going out, that didn’t really come into play,” Birkeland told the audience. “What we had was a lot of experienced people who had spent a lot of time in backcountry terrain that were caught and killed in avalanches.”

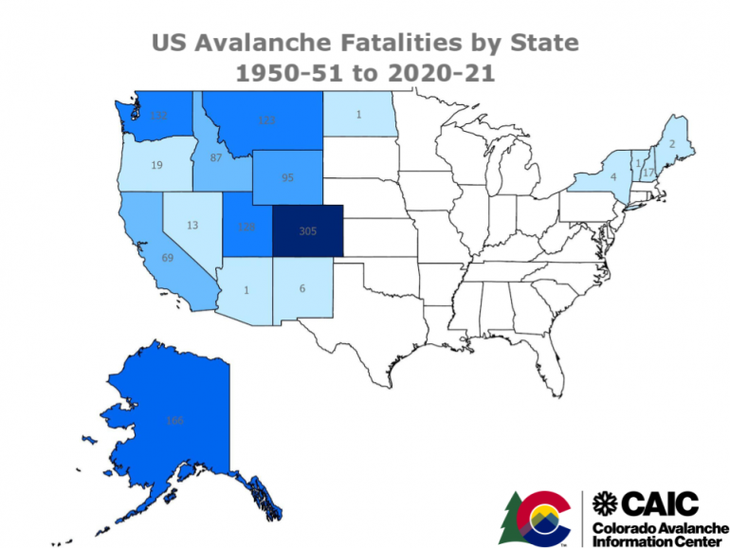

Intrigued, I reached out to Birkeland, Director of the U.S. Forest Service National Avalanche Center, and Erich Peitzch, an avalanche forecaster and physical scientist for the USGS, based in Glacier, Mont., who had conducted extensive research on the topic. These two experts, along with a few other colleagues, published a paper in 2020 about the trend of older avalanche victims from 1950 through 2018. But despite their research, both say it’s difficult to pinpoint just one reason for the trend.

“My theory is that with people who’ve been backcountry skiing a long time, they get a system that works for them and they stick to it,” says Birkeland. “When I hear about older people dying in avalanches, I think about how you can be out backcountry skiing for a long time and end up being really lucky. So often, the snow is stable and you can get away with bad decisions, but it only takes one to kill you. A lot of people get lucky but don’t understand that they’re lucky—they think they’re good.”

Birkeland brings up the example of the massive avalanche south of Bridger Bowl on Saddle Peak in February 2010. A snowboarder broke a cornice off from the top of the ridge that triggered a five-foot deep, 1,000-foot wide avalanche which narrowly missed killing several people scattered throughout the slope.

When Bridger Bowl opened up sidecountry access to Saddle Peak in 2008, Birkeland remembers the concern about high school and college kids who would likely get into trouble. As a result, parents and teenagers were targeted with an awareness video, mailed with each season pass purchase, highlighting the dangers of skiing in avalanche terrain. “But when you look at who was on that slope when it slid, it wasn’t the kids. The people out there were in their 40s, 50s, and 60s. A bunch of middle-aged guys all justifying why they were there and why they thought it was okay to ski that day.”

That’s not to say teenagers and new backcountry skiers aren’t prone to taking bigger risks. But avalanche education has targeted the younger demographic, and it seems to be working. “Young people are flocking to avalanche classes. Maybe we’ve been so successful in reaching young people over the last 15 years, we need to start encouraging older people to re-up their education,” Birkeland says, citing another example of the Know Before You Go program which has been successfully implemented in high schools nationwide. “The question is how do we reach these folks and get them to go back to school?”

Related: Experts are rethinking avalanche education to reduce fatalities

Folks who have been skiing in the backcountry recreationally for 20 or 30 years are often decades away from their last avalanche course and both Birkeland and Peitzch pointed to a big gap in education for older, more experienced users. “I think a lot of those folks have been in the backcountry a long time and have good knowledge of how to travel. But maybe they’ve never taken a Level 1 or maybe they did but it was 20 years ago,” says Peitzch. He points to research on avalanche formation and mechanics, new stability tests, communication strategies, and a better understanding of how humans make decisions. The truth is, avalanche education has taken big leaps in the last few decades.

While a push for more continued education for experienced users will no doubt be productive, Peitzch and Birkeland both emphasize that it’s still hard to nail down exact reasons for the trend since gathering data on backcountry skiers, compared to resort skiers, is incredibly challenging. “We don’t have the parent population,” says Peitzch. “We don’t necessarily know how many people are out recreating in the backcountry, so we can speculate, but until we have more data on what the demographics really look like, we can’t say for sure.”

Despite the uncertainty, Peitzch points to awareness as a positive force. “As someone who is in my 40s, right square in the middle of that age group, just recognizing that this is a pattern—even if we don’t know the answers—can hopefully be something we incorporate into our mindset and decision making.”