Products You May Like

A teenage girl in California who shut down a toxic oil-drilling site; a Nigerian lawyer who got long-overdue justice for communities devastated by two Shell pipeline spills; two Indigenous Ecuadorians who protected their ancestral lands from gold mining. These are just some of the inspiring winners of this year’s so-called “Green Nobel Prize.”

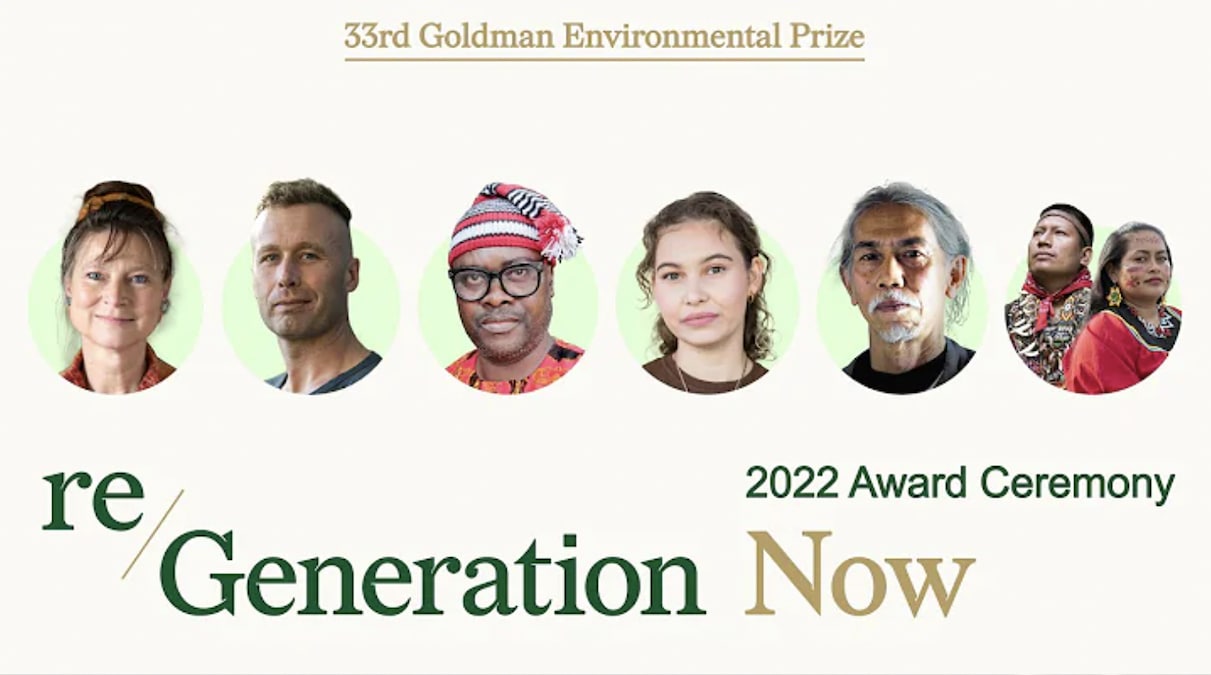

The Goldman Environmental Foundation today announced the seven 2022 winners of its annual Goldman Environmental Prize, which is the highest honor one can receive for participating in grassroots environmental activism.

“While the many challenges before us can feel daunting, and at times make us lose faith, these seven leaders give us a reason for hope and remind us what can be accomplished in the face of adversity,” Goldman Environmental Foundation vice president Jennifer Goldman Wallis said in a press release. “The Prize winners show us that nature has the amazing capability to regenerate if given the opportunity. Let us all feel inspired to channel their victories into regenerating our own spirit and act to protect our planet for future generations.”

The winners will be officially announced at an online ceremony at 5 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time hosted by actress and activist Jane Fonda.

However, you can already view the winners and their stories on the prize’s website.

Nalleli Cobo: At the age of 19, Cobo led a coalition that shut down a toxic oil drilling site in her South Los Angeles community. Cobo began fighting to shut down the site, which caused health problems like nosebleeds and headaches for her and other residents, when she was only nine. She was diagnosed with cancer when she was 19. Now cancer-free at 21, the illness left her unable to have children. She plans to run for U.S. president in 2036, The Guardian reported.

“I kept fighting because no child should be denied the right to play outside or open windows like I was. It’s powerful to know that we, an invisible community, made this change,” she said, according to The Guardian.

Marjan Minnesma: Minnesma developed a unique legal strategy to compel the Dutch government to take action on the climate crisis. She argued that the government had a “duty of care” towards its citizens that it was failing by dragging its heels to reduce emissions and successfully sued the government to slash emissions by at least 25 percent of 1990 levels by 2020. The government appealed twice, until the highest court in the nation upheld the decision, marking the first time that citizens had successfully held their government to account for climate inaction.

The ruling was “the strongest decision ever issued by any court in the world on climate change, and the only one that has actually ordered reductions in greenhouse gas emissions based on constitutional grounds,” Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University director Michael Gerrard said on the prize website.

Alex Lucitante and Alexandra Narvaez: Lucitante and Narvaez are two members of the Indigenous Cofán of Sinangoe community, whose ancestral territory covers 79,000 acres of biodiverse rainforest in northern Ecuador. When Lucitante and Narvaez discovered that the Ecuadorian government had granted mining concessions in the area without consulting their community, they led a movement to protect their home They won a 2018 legal victory in which the court canceled the 52 concessions, setting an important precedent for protecting Indigenous land rights in the country.

“As women we have to defend Mother Earth, to speak out for the future of our children and defend our way of life in spite of the machismo and being afraid. It’s been beautiful to be part of this struggle with other women from my community,” Narvarez said, as The Guardian reported.

Niwat Roykaew: Roykaew is a retired schoolteacher in his 60s who worked to organize the communities that live along the Mekong River on the Thai-Laotian border. He observed first-hand the impacts of development on the river, and worked to stop a rapid-blasting project to allow Chinese cargo ships to pass. His efforts were successful, leading the Thai government to cancel a transnational project due to environmental concerns for the first time.

“The Mekong is like a mother to us, she gives us everything we need,” Roykaew said, as The Guardian reported. “It’s important to inform and empower the powerless so they know as citizens they have the right to ask questions and oppose multimillion-dollar projects by big countries.”

Julien Vincent: From extreme bushfires to bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia is extremely vulnerable to the impacts of the climate crisis. At the same time, it is the world’s leading coal exporter by value and the second by volume. Vincent decided to address this by trying to cut off the financial tap. His group Market Forces managed to get Australia’s four largest banks to agree to stop funding coal projects by 2030. The country’s leading insurance companies have also agreed not to underwrite new coal projects.

“That was years of campaigning – we had divestment days, shareholder actions,” Vincent told The Guardian of his actions in a profile. “The lesson was that you can get to a point of mutual understanding and trust. We were not satisfied with what they were doing, and they didn’t appreciate our campaigning. But we had years of meetings and there was an understanding. It’s about being genuine and sincere.”

Chima Williams: In 2004, a Shell-operated pipeline in the Niger Delta caught fire, burned farmland and mangroves and polluted a lake. The next year, another pipeline leak spewed oil into land and drinking water for 12 days before it was contained. Shell blamed sabotage for the incidents, but Williams, an environmental lawyer, worked with the impacted communities to take the company to court. In 2021, the Court of Appeal of the Hague ruled that both Royal Dutch Shell’s Nigerian subsidiary and the parent company Royal Dutch Shell had a responsibility to prevent spills.

“This is the first time a Dutch transnational corporation has been held accountable for the violations of its subsidiary in another country, opening Shell to legal action from communities across Nigeria devastated by the company’s disregard for environmental safety,” the Goldman Environmental Prize website wrote.

The Goldman Environmental Prize was first established in 1989 in San Francisco by philanthropists Rhoda and Richard Goldman, according to the press release. Since then, it has been awarded to 213 people from 93 different countries.