Products You May Like

Get full access to Outside Learn, our online education hub featuring in-depth fitness, nutrition, and adventure courses and more than 2,000 instructional videos when you sign up for Outside+

Sign up for Outside+ today.

So far in 2023, 15 people have been rescued from the slopes of Mount San Antonio (also called Mount Baldy), two people have died, and actor Julian Sands remains missing. Why is Baldy so dangerous?

If you live in southern California and consider yourself in the least bit outdoorsy, then you probably spend your weekends hiking. From Runyon Canyon in the middle of Hollywood to any of the 264 named peaks in Los Angeles County, trails abound, the usually mild weather suits, and the region’s obsession with fit physiques compels. And, if you’ve ever lived in or traveled to the area, you’re probably familiar with Mount Baldy. Its 10,064-foot peak looms above the Los Angeles skyline, the bare, southern-facing bowl that gives it its nickname clearly visible across the city.

#BREAKING Missing hiker Jin Chung has been found alive. He is responsive and was taken to a hospital for evaluation. Chung went missing Sunday after heading to #MtBaldy.@KTLA pic.twitter.com/98GSnFdpK9

— Shelby Nelson (@KTLAShelby) January 25, 2023

In the eight years that I called LA home, I hiked Baldy and surrounding peaks in the San Gabriel mountains numerous times. Most days, Baldy is no different from any other popular hike in SoCal. It’s a little taller than most, sure, and the most popular 11.3-mile loop through about 4,000 feet of elevation takes a bit longer than most other day hikes. But otherwise it’s the same mix of loose sand covering loose rock spread across steep slopes that you’ll find anywhere else in the area—you’ll just be rewarded with better views once you reach the top.

But a couple of things make Baldy different. For starters, its elevation. The general rule of thumb is you lose 3.3 degrees Fahrenheit for every thousand feet of elevation you gain. So, not withstanding any other weather conditions, Baldy’s summit will be 33 degrees colder than the beach.

For most of the year, that’s actually refreshing. If it’s 90 degrees in Hollywood, it’ll be 57 on top of Baldy. At the height of summer, it makes sense to spend an hour or two sitting in traffic, so you can reach the trailhead at Manker Flats. But right now, near the tail end of January, it’s not 90 degrees in Hollywood, it’s reaching the low forties at night. Most Angelenos would consider that bone chilling and have never experienced anything like the negative-four-degree wind chill Mount Baldy will see early Thursday morning.

The warnings are up on the way to #MtBaldy as #searchandrescue teams to look for a missing actor. There’s also a search for another #hiker in the Southern California #mountains. More @ABC7 at 5. pic.twitter.com/DkkiiuVdR9

— Sid Garcia (@abc7sid) January 20, 2023

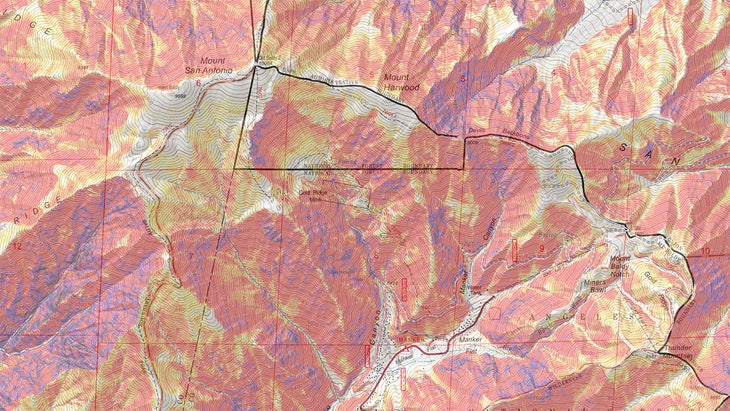

Baldy’s winds also make it unique. Speeds will reach 60 MPH on Thursday morning, according to the National Weather Service. Not only is Mount Baldy the tallest peak in the San Gabriels, but that east-west range represents the last barrier between the Great Basin and the southern California coast. Each winter, as high pressure systems build across Nevada, the dense, heavy air it produces flows downhill towards Los Angeles from the northeast. When it reaches the San Gabriels, it speeds up and compresses as it blows over them. Known as the Santa Anas, these winds are notorious for driving the most destructive wildfires. Crossing the Devil’s Backbone, a narrow east-west ridge that you must brave to reach Baldy summit along its most popular route, hikers will be exposed to these winds at the absolute peak of their force.

That narrow ridge is not one of the things that makes Baldy unique. Many of the 2 million people who hike Runyon Canyon each year take a tumble on its steep, loose terrain at some point. I know I have dozens of times. While the underlying backbone of these mountains might be granite, it’s mixed with sandstone and shale, and the patchy chaparral that struggles to cling to it does little to hold the soil in place. Sharp rocks poke through a loose, sandy cover, crumbling as they’re exposed to the elements. It doesn’t matter if you wear knobby trail runners or lugged hiking boots, nothing grips this stuff with anything approaching sure footedness.

And that gets even worse in the winter, because there’s one last thing that makes Baldy unique: skiing. That’s right, there are actually 26 ski runs and four lifts located on the mountain’s eastern side. According to the resort’s Instagram page, they opened the fourth lift last weekend, an event that’s happened rarely in the last decade, as extreme drought conditions have plagued California.

Put all that together—cold temperatures, high winds, steep, exposed, slippery terrain, and the potential for snow—and make it proximate and easy to access to all 24 million people who live across the SoCal urban conurbation, and you can see why rescues, injuries, and deaths are inevitable. Put enough people in situations with even a minimal amount of risk, and eventually the numbers just add up.

Be prepared for extreme alpine conditions–e.g., Mt. Baldy and Icehouse Canyon areas, Mt. Islip, etc. #Safety #SafetyFirst

– pic.twitter.com/qMg8eeTIcA— Angeles National Forest (@Angeles_NF) January 21, 2023

Of course, another factor is exacerbating Baldy’s danger this winter. A relentless string of atmospheric rivers dropped 32 trillion gallons of water on California in just three weeks. And Baldy got its share, too, with reports of up to two feet of snowfall in the area. That snow has variously mixed with rain, and gone through freeze-thaw cycles, producing what the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department (one of multiple entities responsible for search and rescue missions in the area) is calling, “extreme alpine conditions.”

Rescuers searching for Sands—an experienced mountaineer—have reported multiple avalanches on the mountain, and have variously been prevented from traveling by foot, helicopter, or both, due to ice, avalanche risk, and high winds.

Baldy may be part of the Los Angeles skyline, but that doesn’t mean it’s a not a real mountain, complete with all the risks and draw any mountain holds. The reason Mount Baldy kills is simply that it’s popular.