Products You May Like

Hard is in. But to hell with obstacle races and manufactured difficulty (50 miles in a day! Barefoot! Backwards!). These 9 hard hikes offer true challenges of all types — grueling, really scary, and tricky to plan—and payoffs you can only get one way. Go forth and conquer—if you dare.

Backpacker’s Pick: West Coast Trail, British Columbia

As dramatic as Italian opera—and just as hard to get through—this 47-mile, six-day footpath on Vancouver Island’s west coast traces the seam between land’s end and the sea. “It’s the most exquisitely beautiful coastal hiking,” says guidebook author Tim Leadem (Hiking the West Coast Trail), who’s logged nearly 20 completions. “Watching gray whales spouting with 30-foot Tsusiat Falls crashing behind me is the kind of unforgettable, only-on-the-West-Coast moment that keeps bringing me back.”

But witnessing such primordial gorgeousness doesn’t come easy. Capricious tides trap hikers against unscalable cliffs. Hypothermia is a real threat, thanks to drenching mists, abundant rain, and cool temps (averaging just 57°F in the height of summer). Waterlogged bogs, slick ladders, and cable car crossings challenge backpackers’ balance. “I’ve encountered knee-deep mud, and if you slide off a boardwalk, it’ll be hip-deep,” Leadem says. It all adds up to an average of 70 rescues per season—but successful hikers call the journey a life-changer.

Hike It

Reserve a permit, or show up for first-come, first-serve spots (most hikers get a permit within a day or two). You can also start at Nitinat, the trail’s midpoint. August is easiest, Leadem says, because “a few weeks of good weather have generally dried up the most notorious mud patches.” Bring a synthetic bag (best defense against the ever-present mist) and load your pack for maximum stability. Carry a tide chart, cross beach segments at low water, and don’t risk the coastal shortcut at Adrenaline Creek (it can be deadly).

Wrangell Plateau to Dixie Pass, Alaska

Even by Alaska standards, the Wrangells are big and wild. “There’s none of the hand-holding (training from rangers, buses) you find at Denali,” says photographer Matt Hage, who helped pioneer this 56-mile route from Wrangell Plateau to Dixie Pass. “It combines everything that makes Alaska tough—and amazing.” You’ll ford two large, glacial rivers (up to waist deep), bushwhack through dense brush, hike on a glacier, and navigate your own route through grizzly terrain, all to access seldom-seen panoramas of the 16,000-foot Wrangell Mountains. Complete this trek, and epics like the Sierra High Route seem simple.

Hike It

Leave a car at Dixie Pass trailhead off Strelna Road and book a flight to Wrangell Plateau. The six-nighter’s first big obstacle: crossing Long Glacier, which slopes to the ground (no ropes or ice axe needed, but bring microspikes). Day three, hike to Kluvesna River for boundless views of snaggly peaks, and cross the river the next morning (when flows are lower). Day five starts with the Kotsina River crossing; bushwacking up the Rock Creek Valley fills day six, which ends beneath Dixie Pass. Finally, hike over Dixie to Strelna Creek, picking up the established trail to reach your car.

Agassiz Peak, Arizona

Agassiz is Arizona’s forbidden fruit. Viewed from Flagstaff, this 12,360-foot peak looks loftier than neighboring Humphreys (Arizona’s actual high point; Agassiz is second). Summit-baggers yearn for its conical top, while skiers covet its north-facing powderfields. And, in fact, winter offers the only legal window of opportunity: To keep hikers from trampling the ultra-rare San Francisco Peaks ragwort (a fragile tundra flower that grows only on Agassiz and Humphreys), the Forest Service prohibits walking on bare ground above treeline—and snow rarely blankets these wind-scoured ridges (rule-breakers incur a $500 fine).

“You need a 2-foot storm followed by calm, which almost never happens,” says Flagstaff powderhound Brad Schorb, who’s summited Agassiz just four times in 12 years. And the same snow accumulations that permit a legal climb spike the avalanche danger. But if you can reach this summit, you not only bag one of the state’s highest, most coveted peaks, but skiers can enjoy euphoric powder turns on the return.

Hike It

Obtain a Kachina Peaks Wilderness Access Permit from the USFS (free). Check storm accumulations at the Arizona Snowbowl (a ski resort on Agassiz’s lower slopes), consult kachinapeaks.org for avalanche forecasts, and monitor winds via noaa.gov. “More than 25 mph, and there’ll be no snow left,” Schorb says. Equipped with avalanche safety gear and know-how, start skinning or snowshoeing from Agassiz Lodge (at 9,500 feet) no later than 6:45 a.m. in order to clear the ski area boundary by 8:00; follow Snowbowl’s recommended uphill route, posted daily on the corkboard by the parking lot. (Option: If the resort’s backcountry zones are open, you can take the lift up to 11,500 feet.) At treeline, take off skis and put on microspikes to bootpack 700 vertical feet up the ridge to the summit, where views extend 70 miles to the Grand Canyon.

Cabeza Prieta Pass, Arizona

Vast but trailless, Cabeza Prieta attracts far more Jeepers (on the Camino del Diablo) than hikers (about a dozen annually). And that’s a shame, because from a truck you won’t notice elf owls nesting in holes bored into 20-foot saguaro cacti, or savor scarlet ocotillo blooms. And you can’t appreciate the profound silence—the desert’s real gem. “It’s just so quiet that you get lost in your thoughts,” says biologist Curt McCasland, who’s traversed the refuge four times on foot.

But such feats aren’t for the careless. “We have fatalities every year,” says Sid Sloane, the refuge manager. Most are migrants and drug smugglers who routinely sneak across these 1,000 square miles of ultra-remote Sonoran Desert bordering Mexico, but hikers occasionally succumb to the heat and aridity. Summer temperatures regularly reach 120°F, and the refuge contains no surface water besides potholes, or tinajas, which sustain bighorn sheep and other wildlife.

Hike It

Hike this 26-mile overnight in late February, when roads have dried from January rains and saguaro, ocotillo, and sand verbena explode into bloom. Carry at least 6 liters of water per person per day (caches are unreliable because of the border traffic) and leave a few gallons in your vehicle. From Tule Well, drive a 4WD 3.3 miles west, park, and hike north following an easy, (closed) former Jeep track among granite spires on the west flank of the Cabeza Prieta Mountains. After 6.7 miles, turn right and follow the old track east to 1,500-foot Cabeza Prieta Pass, with mountain views and slightly cooler temps. Camp at 11 miles, in the sandy washes on the mountains’ east side. Next morning, dayhike north 2 miles into Surprise Canyon, where steep granite walls funnel storm water to a garden of saguaros, then retrace your steps to the Camino.

Iron Mountain, California

Summit solitude is a rarity near Los Angeles—thanks to its 4 million residents, you’ll see a dozen other hikers atop most San Gabriel peaks—but you have a good chance of claiming 8,007-foot Iron Mountain to yourself. Its summit stands shoulder-to-shoulder with giants such as 10,064-foot Mt. Baldy and 9,399-foot Baden-Powell, so its views trump nearly every other panorama in the range.

But hikers are few, thanks to 7,200 feet of elevation gain over 7.5 miles (14,259-foot Longs Peak in Colorado climbs just 5,000 vertical feet in the same distance). “Iron’s route is steep the whole way, but the final 2 miles seem near-vertical,” says L.A. local Jeremy Boggs, an avid hiker who calls Iron Mountain his “badge of honor.” You’ll pass no water sources along the way, so most hikers tote at least 5 liters. But tagging the summit is “uniquely satisfying,” Boggs says. “Even though it’s right next to millions of people, it still feels remote.”

Hike It

Buy an Adventure Pass ($5/day, $30/year) at area gear shops or Forest Service offices; at the trailhead, self-register for a free wilderness permit. Hike in spring (March to May) or fall (October to early December) when afternoon temps typically stay below 90°F. Wear long pants and sleeves to guard against needle-sharp yucca, and bring a headlamp (many hikers finish after sunset). Trekking poles are a must, especially for the descent. Starting from the Sheep Mountain Wilderness trailhead no later than 5 a.m., follow the Heaton Flat Trail for 3.5 miles to Allison Saddle (4,582 feet). Cache some water here for your return, then hike north, following an unmaintained user trail along Iron Mountain’s roller-coaster ridgeline. The final mile gains a quad-quivering 2,000 vertical feet before reaching the flat summit. Recharge here, savor the San Gabriels’ best scenery, and retrace your steps to the trailhead.

Coastal Prairie Trail, Florida

In the Everglades, water and sky rule—think Technicolor sunsets and flocks of cormorants. But solid ground is scarce, which makes the 7.5-mile (one-way) Coastal Prairie Trail your best ticket into this waterlogged wilderness. The old roadbed, made of pulverized coral (marl), is a pleasant, packed-dirt path—when dry. Wet, it turns to foot-grabbing muck. And summer’s 90°F temperatures are hellish, though “it’s the bugs that make you suffer,” promises John Roark, a park volunteer who’s been exploring these wilds for 40 years.

Venture off-trail, and you’ll encounter pudding-thick mud, skin-slicing sawgrass, and waters choked with cottonmouths and mangrove roots. “Hikers have disappeared here,” Roark says. “It’s real wilderness.” Visit in January or February, though, and you can plumb these wilds in relative comfort: Mud is scarce, temps are mild, and a solitary beach campsite lets you savor pastel skies.

Hike It

At Flamingo Visitor Center, get a permit to camp at Clubhouse Beach (mile 7.5; carry at least 2 gallons of water per person). Next morning, wander west about .5 mile off-trail through sawgrass and mangroves to ogle cardinal airplants (flowering bromeliads that grow in tree branches) and enjoy birdsong. Return to the trail and enjoy the relatively easy walking back to Flamingo.

Baldpate Mountain, Maine

Call it Maine’s Stairway to Heaven: This stretch of AT beelines to sky-kissing summits in just 2.9 miles, making this one of the East’s shortest, most direct routes above treeline. But speedy ain’t easy. The most infamous mile is elevator-shaft steep, sustaining a 50 percent grade between the Baldpate Lean-to (at 2,645 feet) and the 3,662-foot summit. But you’ll need more than fitness to stay upright, because the entire climb (and descent) involves a web of foot-trapping tree roots atop a sheet of bedrock slickened by algae and runoff: Step on greasy roots or rocks, and your foot skates away beneath you; step between the roots, and you trip. Your reward for sure-footed perseverance? One of the best 360-degree views in Maine, with no roads or towns in sight and layers of peaks fading into the distance.

Hike It

Wear sticky, lugged-sole hiking boots for the 2.9-mile (one-way) hike from the Table Rock trailhead (off ME 26 north of Newry) to Baldpate Mountain. The first 2 miles are rocky but dirt-packed; Baldpate Lean-to signals the start of the Menacing Mile. For the return, use trekking poles, which prevent faceplants after the inevitable slips and stumbles. Side-stepping (placing your boots parallel to tree roots, as if they were ledges) improves traction and reduces entanglement. Overnight option: Camp at Table Rock, via a .8-mile, blue-blazed spur at mile .8.

Blacktail Buttes, Idaho

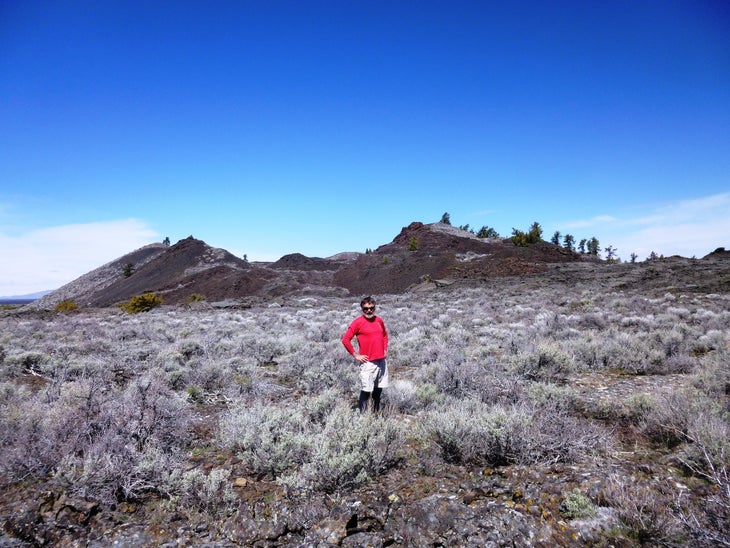

Like a vast Zen garden, these lava flows simplify the landscape to bare elements: black volcanic earth, azure sky, an occasional upstart shrub eking out a life among the otherworldly rocks. Inky lava displays red, yellow, and green lichens, sometimes even a startling blue varnish that makes stones resemble dragon scales. You feel like an alien here—especially if you venture off the monument’s few trails. “You see no evidence that anything passed before you—no firepits, no trash, no footprints or game trails,” says photographer Craig Wolfrom, who’s logged some 80 off-trail miles in the Craters’ backcountry. But heat radiating off the rocks and very scarce water sources make multiday travel hellish in any month but April, when lingering snow can quench hikers’ thirst. And solid navigation skills are a must: Dayhikers have died of exposure after getting lost amidst the cinder cones and lava caves.

Hike It

Tilted, abrasive rocks call for a freestanding tent with a compact footprint, a ground cloth, a puncture-proof foam sleeping pad, and mid-height, sticky-soled approach shoes. Pick up a free backcountry permit from the entrance station or visitor center, then drive to the Tree Molds trailhead to start this three-night, 30-mile out-and-back to Blacktail Butte, on the edge of a no-man’s-land.

Day one’s 4 miles follow the Wilderness Trail past cinder cones and lava trees to Echo Crater (camp in the shelter of its limber pines, just west of potholes that often hold water in spring). Rise early and top off your bottles for a stout second day: The trail peters out after a mile, leaving you to chart your own course for 5 miles though dense sagebrush and pahoehoe lava to Vermilion Chasm. Camp in this pine-filled valley and gaze down into the Great Rift (the fissure that emitted the lava you stand on): This 100-foot-wide crack in the ground is lined with towering stacks of volcanic rock on both sides. Next day, dayhike south 5 miles to Blacktail Butte, which shelters splatter cones and an improbably lush valley within its slickrock walls, then return to camp at Vermilion. Hike all the way out on day four.

White Pinnacle Peak, Nevada

You’ll be tempted to pack a parachute to visit this airy, confidence-testing point of sandstone hovering 1,500 feet above the valley floor. Though it’s a subpeak of 7,070-foot Mt. Wilson, it upstages its superior with greater thrills and a shorter approach (4 miles round-trip). But half the route is off-trail, and involves stemming up sandstone narrows and scrambling across small foot- and handholds. And the final 75-yard ridgewalk above sheer, 1,000-foot cliffs unnerves even the most confident climbers, making this hike both a mental and physical challenge. “You’re just a step away from a fatal plunge,” says Bob Sihler, an experienced scrambler who summitted 5,550-foot White Pinnacle on his third try. “The exposed parts aren’t technically hard, but there’s no room for error.” That and the wide-angle views give this peak its unique thrill: Suspended in air, you feel more like a hummingbird than a hiker.

Hike It

Wear sticky-soled approach shoes, carry a 30-foot rope for hoisting packs, and go on a dry day. “The sandstone holds crumble when wet,” says Sihler, who once had to turn back within sight of the summit because of rain. From the First Creek Canyon trailhead on NV 159, follow the trail for a mile, then veer right on a user path to a seasonal waterfall. Cross the wash, and enter the gully on looker’s right of White Pinnacle Peak. Scramble up a class 4 crack and stem up the chimney, hauling packs with rope. Then scramble up a sandstone slope to the exposed, 75-yard ridgeline to the summit.

Originally published in 2014; last updated December 2021