Products You May Like

Edge of the Glacier Trail, Kenai Fjords National Park, Alaska

Last summer, Exit Glacier looked more like a snowball bobbing in a pond than the once-mighty arm of the Harding Icefield. Last year alone, the glacier retreated 293 feet, which isn’t even the most alarming part. Melting now continues into winter: October through May, daily temperatures at the glacier’s foot now stay above freezing half the time. Twice, park officials even extended the Edge of the Glacier Trail to chase Exit’s toe. Hike the easy, 2-mile round-trip now to ogle the glacier’s gullies of blue ice and listen to its crackling crawl before it makes good on its name.

Trailhead Exit Glacier Nature Center (60.1880, -149.6295) Season June to November Permit None Contact

Arizona Trail, Tonto National Forest, Arizona

The views from 4,377-foot Picketpost Mountain couldn’t be more Arizona: red dirt expanses and dusky hills pocked with 20-foot-tall saguaro cactuses, craggy desert towers. Yet, there, amid arguably one of the prettiest stretches of the 800-mile Arizona Trail, machines will begin digging the Resolution Copper Mine in as soon as three years. The operation will affect popular rock climbing in the area and inch scary-close to Native American archaeological sites.

Tackle the Superior section of the Arizona Trail now, before the planned reroute around the mine leads hikers away from Picketpost’s iconic vista. From the Picketpost trailhead, follow the Arizona Trail south for .3 mile, then take the 2-mile spur to Picketpost’s 360-degree summit view. Return to the Arizona Trail, and follow it 9 more miles past saguaros and eroded rock knobs to camp at Trough Springs (BYO water). Return the way you came.

Trailhead Picketpost (33.2722, -111.1763) Season September to May Permit None Contact

Grinnell Glacier Trail, Glacier National Park, Montana

You’ve heard that this park’s 23 namesake features are disappearing, but maybe thought you had plenty of time to see them. Bad news: Revisions to air temperature modeling indicate the zero-ice date may be in 2020. In this case, there is literally no time to waste to see the land and its architect in the same viewshed.

One of the first to go might be Grinnell Glacier, which has lost 40 percent of its original might in the last half-century. Steady melting keeps the ice retreating higher into the cirque that cradles it, while calving expedites the process (like in 2015, when a 10-acre chunk broke off into Upper Grinnell Lake). Admire Grinnell’s 110-acre remains by following its eponymous trail 5.5 miles to Upper Grinnell Lake, where the glacier’s crumbling toe adds to the startlingly blue water every year. Scan the steep-walled cliffs surrounding the lake to see two more glaciers: Gem to the south and Salamander, which once touched Grinnell, 700 feet above it. Look for mountain goats on the cliffs, glimpse alpine wildflowers that thrive in snowmelt, and listen for the squeak of marmots on the rocky moraine—all of these cold-loving species will struggle and decline without the park’s rivers of ice.

Trailhead Grinnell Glacier (48.7971, -113.6684) Season July to October Permit None Contact

Long Trail, Mt. Mansfield State Forest, Vermont

Close your eyes and picture fall glory in Vermont’s north woods. It’s the sort of scene that’s equally austere and comforting: blazing tunnels of crimson and amber leaves, high-elevation balds filled with alpine tundra, huge moose browsing at the water’s edge.

It’s not all going away, but it will change. Scientists are already noting the slight uptick in temperatures in Vermont, which has given rise to bark-boring pests that attack hardwoods. Ashes, birches, and, most notably, maples are dying off, and, though scientists can’t say when they’ll disappear from the landscape, it will likely happen within the next few decades. Alpine tundra, the state’s rarest ecosystem, may follow. Moose may migrate away.

Cheer yourself up by experiencing Vermont the way nature intended on the 28-mile segment of the Long Trail from Bolton to VT 15 (leaving a car at both locations). It’s a roller coaster, gaining 9,500 total feet—including a 2,600-foot grunt up Mt. Mansfield, the state high point—but there’s no better section for notching big views from tundra-topped summits. Do it in three days, overnighting at Twin Brooks (scan for moose here) and Sterling Pond Shelter ($5). The Long Trail has its charms in every season, but autumn’s sensory overload is the best—for now.

Trailhead Bolton Notch Road (44.3838, -72.9147) Season Year-round Permit None Contact

Sliding Sands Trail, Haleakala National Park, Hawaii

Life’s not easy as a silversword. The rare-but-iconic plant has had to fight for its life atop Maui’s 10,023-foot Haleakala for the past 300 years, first dealing with hungry, invasive goats, then overeager, non-LNT-abiding tourists. Now the spiky, silver rosette faces another battle: climate change. Between warming temps and disrespectful hikers, the Haleakala silversword population has declined 60 percent since the 1990s—now numbering just 40,000. See the threatened plants on the 9.2-mile, out-and-back Sliding Sands Trail, which descends into the volcano’s crater. The easy-to-identify silverswords pop against the deep-red dirt.

Trailhead Keonehe’ehe’e (20.7141, -156.2511) Season Year-round Permit None Contact

Greenstone Ridge Trail, Isle Royale National Park, Michigan

Gray wolves haven’t always lived on Isle Royale. They arrived in the 1940s, having migrated across an ice bridge from Ontario. But such ice bridges are now rare—winters have become warmer and windier—and with no influx of fresh breeding stock from the mainland, Isle Royale’s most celebrated residents have dwindled in number from 50 in five packs to just two inbred animals.

That could spell disaster for the island’s entire ecosystem. With no predators to check the island’s 1,600 moose, biologists predict that the browsers will mow down every balsam fir and aspen sapling on Isle Royale, causing a disastrous ecological ripple effect. Now, the Park Service must decide whether to import wolves to reinvigorate the population—or let nature take its course.

To listen to what may be the island’s final howls, hike a two-night, 21-mile loop on the island’s east end (where the remaining wolves were born and still spend most of their time). From Rock Harbor, hike 7 miles west along a shoreline trail before camping at Daisy Farm. Next day, hike northeast for 7 more miles—following a portion of the Greenstone Ridge Trail—to Mt. Franklin. Overnight at Lane Cove and then close the loop with 7 more miles to Rock Harbor. Alternatively, if you’ve got a boat, dock at Tobin Harbor to dayhike through the east end’s wildest corner: Head 1 mile north through lichen-draped firs to Lookout Louise and its views of forested fingers splintering into Lake Superior, then hike 5 miles west to conduct a wolf-spotting mission along the Greenstone Ridge Trail.

Trailhead Rock Harbor (48.1461, -88.4861) Season April to October Permit Required for backpacking (free); obtain aboard the ferry. Contact

Trail and Lost Creeks, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, Alaska

With Alaska’s largest system of glaciers and permanent snowfields, a quarter of Wrangell-St. Elias hides under a shield of ice. As in other Alaskan parks, that frozen layer is melting—giving caribou fewer places to escape from biting insects. But that’s not the only issue the deer have with warming temps. A longer growing season means that new seedlings—the highly nutritious sprigs that nourish babies—no longer coincide with calving season. Plus, hotter summers mean more fires, which destroy the lichens that the adults rely on.

All said, Wrangell’s Chisana caribou herd, which once was 1,800 animals strong, has been dwindling for more than a decade. Try to spot the 700 or so remaining deer—plus Dall’s sheep—in the northeast corner of the park before they make a permanent move for colder year-round temps. Connect the gravel bars, canyons, and dwarf willow and birch benches of the Trail Creek and Lost Creek drainages for a 22.5-mile loop (get prepped, right).

Trailhead Trail Creek (62.5227, -143.2220) Season June to September Permit None Contact

Mammoth Crest Loop, Inyo National Forest, California

Whitebark pines have been fighting the good fight for a long time. Most of these gnarled trees are 600 to 700 years old—that’s a lot of time doing battle with the weather in the harshest high-elevation zones across the West. But though they can withstand the endless lashing of icy winds, whitebarks are practically defenseless against pests like pine beetles and fungi like blister rust. Unfortunately, both have reached epidemic levels thanks to recent warming trends, spurring die-offs from Washington to Wyoming. With no whitebarks, expect smaller plants and animals that use the trees for shelter or food (like Clark’s nutcrackers) to follow suit.

Some of the healthiest of the remaining whitebarks live in California’s southern Sierra, where the arid climate discourages pests. To wander among their wind-twisted limbs, head to Mammoth Lakes and follow the 13-mile Mammoth Crest Loop, which spends most of its time between 10,400 and 11,200 feet, where whitebarks still thrive. Start at the overnight lot on Lake George Road and climb for 6 miles along the crest of the Sierra, tenting in the rock-studded meadow between Lower and Middle Deer Lake. Next day, continue counterclockwise on unmaintained trail to Silver Divide and down to Barney and Skelton Lakes, just south of the trailhead.

Trailhead Lake George (37.6035, -119.0112) Season July to October Permit Required for backpacking (free for walk-ins, $10 + $5/person for reservations); obtain at the Mammoth Lakes Welcome Center. Contact

Chilkoot Trail, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Alaska

Nicknamed the “Meanest 33 Miles of History,” the Chilkoot may very well be the world’s longest museum. Along the route, hikers pass Gold Rush artifacts from the 1800s like boots, boats, and grave markers (assuming people leave them as they lie). Decomposition, decay, and increasing meltwater are also to blame for the disappearing ruins, which could be totally gone in a few decades. Keep your eyes peeled for artifacts—including an easy-to-spot boiler—on the 7.7-mile Canyon City section. Turn around at the old settlement or pitch a tent near the Taiya River.

Trailhead Chilkoot (59.5120, -135.3466) Season June to September Permit Required ($21); obtain from the visitor center in Skagway. Contact

American Camp Prairie Loop, San Juan Island National Historical Park, Washington

Pay your respects to nature’s comeback kids on this easy, 3.5-mile loop along the Strait of Juan de Fuca: After they were declared extinct in 1908, island marble butterflies were rediscovered on San Juan Island nearly a century later. Though they’re still threatened (and face habitat loss to agriculture), the insects’ population is thought to be around 300. Look for the butterflies (they have flashy, green-and-white wings) in the American Camp area of the national historic park by connecting the South Beach, Bluff, and Grandma’s Cove Trails.

Trailhead South Beach (48.4572, -123.0065) Season Year-round; the butterflies are most common May and June. Permit None Contact

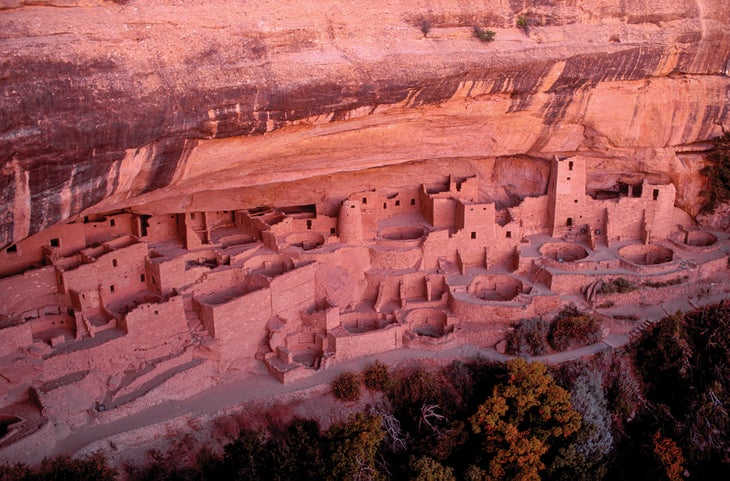

Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

Ancestral Puebloans built their stone dwellings in cave-like alcoves created by erosion. But those same erosive forces may lead to the ruins’ destruction in Mesa Verde and other archaeological sites across the Southwest. Irregular weather patterns due to climate change have increased the frequency of the freeze-thaw cycles that cause cliffs to shed pieces of rock: Meltwater trickles into the cracks, expands as it freezes, and wedges off the outlying stone. The threat even prompted Mesa Verde officials to close access to Spruce Tree House in 2015.

Cliff Palace could follow. This past summer, the park dispatched climbers up the ruin’s surrounding walls and ceiling, where they tapped the rock with hammers to determine its stability. One rock-scaling mission ended up dislodging an 800-pound slab that splintered climbers’ scaffolding as it hurtled to the floor. Better make the .3-mile journey to North America’s largest cliff dwelling sooner rather than later.

Trailhead Cliff Palace Overlook (37.1678, -108.4731) Season April to October Permit Required ($5); obtain at the visitor center. Contact

Florida Trail, Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida

There may be no better taste of the 1,300-mile Florida Trail than its northernmost segment. The 26.5 miles from Navarre Beach to Fort Pickens meander along the slim, sandy finger of Santa Rosa Island, leading hikers across sugary, white-sand beaches and dunes with views across the teal water of Pensacola Bay and the Gulf of Mexico.

But this beachy paradise may soon be underwater. Sea levels are rising all along the Gulf Coast, and although scientists haven’t been able to forecast exactly when saltwater will overwash these barrier islands, the threat is already evident: Storms, now higher and stronger than before, have sliced channels of open water through Santa Rosa Island and obliterated the park’s Fort Pickens Road (necessitating $50 million in repairs and reconstruction). Such floods have also raised the salt content on land, killing off many of the coastal plants.

If you’d rather hike this trail than paddle it, make haste to Santa Rosa Island. From the Navarre Beach Pier, track west along the national seashore’s wild, undeveloped beaches. Scramble though dunes on the bay side of Santa Rosa before pitching your tent at the backcountry Bayview Campsite at mile 12.5 (BYO water). Next day, hike 14 more miles on beachside bike paths and sandy trails through coastal scrub to Fort Pickens ($10 entry fee; campsites start at $26). Note: There are a few water spigots along the way.

Trailhead Navarre Beach Pier (30.3801, -86.8638) Season September to May Permit None Contact

Originally published in 2018; last updated in January 2022