Products You May Like

Receive $50 off an eligible $100 purchase at the Outside Shop, where you’ll find gear for all your adventures outdoors.

Sign up for Outside+ today.

Whether you’re on skis or on foot, heading into the snow-covered backcountry could expose you to dangerous avalanche terrain before you realize it. This guide will give you a basic understanding of the topography that is susceptible to slides so you can avoid the hazards. However, this is not a comprehensive tutorial on staying safe in avalanche country. Use it to know what to look out for—and if you want to explore further in winter, seek out formal training.

The Experts

Brian Lazar

Deputy Director, Colorado Avalanche Information Center, Boulder, CO

Nate Disser

Owner and guide, San Juan Mountain Guides, Ouray, CO

Liz Riggs-Meder

American Institute for Avalanche Research and Education (AIARE), Seattle, WA

Melis Coady

Executive Director, Alaska Avalanche School, Anchorage, AK

Hero Skill: Perfect Partnerships

“Adventuring in the backcountry and taking on risky activities with other people is very intimate and consequential. I would recommend entering avalanche terrain with people that you know well and can always count on for good communication and competence,” Coady says. “Good communication isn’t always just talking. It is understanding when the other person is amped up, tired, fearful, or feeling invincible. So much of that is shown through body language and patterns of behavior which you learn over time.”

Be picky when it comes to choosing partners. Get out on low-risk terrain to test relationships before working up to high-consequence objectives. When you’re ready to go big, make sure it’s with a crew you can trust with your life.

Melis Coady has skied and climbed on all seven continents and worked as a climbing ranger in Denali National Park.

The Avalanche Triangle

Every slide is caused by a combination of three factors: terrain, snowpack, and weather. The avalanche triangle illustrates how these three factors come together. Avalanches occur when all three elements merge, but any one of them could hint that the conditions are unstable. Study these red flags and use them as signs that you should turn back or draw on your avalanche education to carefully consider the circumstances.

Weather

Wind, temperature, and precipitation create complex, dynamic forces within the snowpack and can stabilize or weaken it depending on a number of variables.

Red Flags

• Falling snow. The more it dumps, the more there is to slide. Even a little bit of snow can cause problems.

• Wind. A light breeze can take a small amount of snow on the windward side of a mountain or ridge and turn it into a hazard on the lee side. “The recent wind speed and direction are good pieces of information to keep in mind,” Disser says. Wind-scoured rocks can indicate the upwind side of a peak, and cornices or pillows opposite them can indicate wind-blown snow drifts that can slide.

• Temperature swings and extremes. There’s no measurable correlation between air temp and snowpack, but deep cold and sudden warming can cause instability.

Snowpack

The weather over an entire season builds the snowpack below your feet, creating weak layers of snow, good or bad bonds between them, layers that act as surfaces for others to slide on, or consolidation—when separate layers eventually bond together and solidify. Looking at recent avalanche forecasts and digging pits to assess the deeper layers (which is something you’ll learn in a recreational avalanche training course) is just as important as looking at what’s on top.

Red Flags

• Visible weak layers. An avalanche course can teach you to analyze layers of snow below the surface by digging snow pits.

• Shooting cracks. Cracks slicing across the top layer of snow are obvious signs that it’s unstable.

• “Wumphing.” Taking a step and feeling or hearing the snow settling underneath you is alarming, even if you’re on flat ground. It’s a signal of buried weakness, so retrace your steps to safety.

Terrain

Most (but not all) slides occur in terrain between 30 and 45 degrees. Any gentler and gravity will keep the snow in place; any steeper and the snow tends to slide off before it accumulates. Heavily forested areas are safer than open slopes or gladed hillsides—but if the trees are open enough to ski through, it can slide. Sound like the type of terrain you might find yourself in? Consider taking a course.

Red Flags

• A slope over 30 degrees. Use a slope meter and measure off of a trekking pole laid on the snow. Consider the terrain around you, too: Even if you’re on mellow ground, steep terrain above you can send an avalanche down.

• Terrain traps. What’s below you matters, too. Nearby gullies, cliffs, or other obstacles can cause you harm if a slide washes you into them.

• Open terrain. “If you’re hiking and there are suddenly no trees and you’re not above treeline, you’ve probably walked into an avalanche path,” Disser said. If it slid once, it can slide again; reconsider your route.

Reading the Forecast

Avalanche forecasters use the weather, the season’s precipitation history, and data gathered from digging snow pits in the field to analyze the snowpack all the way to the ground. They use this information to report snow safety forecasts for adventurers (find them all at avalanche.org). Forecasts, which come out daily in the height of the season, are most useful for people who know they’re headed into avalanche terrain (again, take a class if that’s you) but can be helpful for others to get a sense of the overall situation beneath their feet and an idea of what to avoid.

“You can think of it as being laid out in tiers of information,” says forecaster Lazar. Forecasts start with an overarching, broad risk level for an entire region and get more specific, all the way down to identifying individual weaknesses and types of avalanches that are possible. “Our goal is to provide useful information for everyone from the novice to the seasoned profession,” Lazar says. Study this excerpt of an example forecast and the explainers below to begin to understand them.

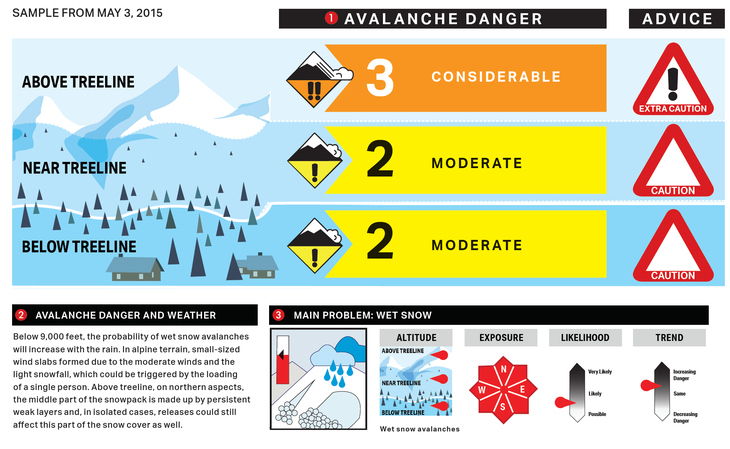

1. The North American Avalanche Danger Scale is the simplest part of a forecast. Five levels (Low, Moderate, Considerable, High, and Extreme) grade the overall risk of an avalanche, taking likelihood, size, and other factors into account. You’ll typically see a rating for an entire region, and most forecasts also show dangers for specific elevations (above, near, and below treeline). “Each level is exponentially more dangerous than the level before it,” Lazar says. Keep in mind that even the lower levels represent real hazards.

2. Most forecasts will offer travel advice or a summary that details where you’re most likely to encounter an avalanche. “The forecaster will prioritize the most important information for the day,” Lazar says. Mentions of specific slope angles, aspects, elevation bands, or terrain features are important to note.

3. Next, forecasts detail one or more specific avalanche problems, or types of possible avalanches, for the day. You’ll see graphics noting where you might encounter certain types of slides. The forecast indicates where on a compass rose these problems are present. An avalanche course can teach you more about these; just know that different types of avalanche problems characterize how a slide might happen.

4. The final part of an avalanche forecast (not pictured above) is the raw data: reports of

actual avalanches, notes from test pits, and data from weather stations. This is the detailed information that forecasters like Lazar use to build the forecast.

Mind Games

Nature might be all-powerful, but human factors play a major role in most avalanche incidents. And when it comes to decision-making in the backcountry, your brain doesn’t always have your back. Heuristic traps cause us to shortcut risk calculations and can lead to foolhardy decisions. Social dynamics such as follower instinct, familiarity with a location, and reliance on past experience are all heuristic traps that can trick you into complacency. Fight them by planning ahead, staying alert, making observations, speaking up, and slowing down.

Should You Take an Avy Course?

“If there’s a chance that you’ll either intentionally or unintentionally end up in avalanche terrain this winter, you should take a course,” says Riggs Meder. With formal training, you’ll learn what causes avalanches, how to identify risky terrain and your exposure to it, and how to handle yourself in a slide or rescue scenario.

Courses that adhere to the guidelines of the American Avalanche Association are the standard for avalanche safety education and a prerequisite for a lot of backcountry adventures. If you’re a backcountry skier, or a cross-country skier or snowshoer who enjoys the steeper stuff, consider taking a course. On the fence? An Avalanche Awareness session—a 1- to 2-hour introduction orienting you to terrain risks—may help you get your feet under you.