Products You May Like

Get access to everything we publish when you

sign up for Outside+.

The first time Ashley Adamo realized something might be wrong was more than 20 years ago. One sign was her cramps. Sure, most of her friends had them before their periods. But Adamo’s were so bad they debilitated her, and nothing she tried brought relief.

Then there was the blood—there was just so much of it. Her heavy periods depleted her of red blood cells, leaving her exhausted and anemic. Not only was it inconvenient, the longtime runner lacked energy to make it through her miles.

“When I first told my doctor how many tampons I was using during an hour on day two of my period,” Adamo says (sometimes more than one, plus a pad) “she was like, ‘that’s not normal. Something else is going on.”

Scans revealed the culprit: Fibroids, benign growths of muscle tissue that form in or around the uterus.

Nearly 8 in 10 people with a uterus develop fibroids at some point in their lives. For Black women, the rate is even higher, with fibroids often appearing earlier in life and causing more complications, disparities researchers are still working to unravel.

Though they’re typically not cancerous, fibroids can have a serious impact on your running—and your life. And as common as they are, delays in diagnosis aren’t unusual.

Symptoms can sneak up slowly over time, and aren’t always easy to talk about or define. They’re also sometimes downplayed by doctors who don’t truly grasp how much they can affect your well-being, says Dr. Kelly Wright, a marathon runner and director of the division of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles.

That was the case for Diane Nukuri, 37, an elite runner for ASICS based in Flagstaff, Arizona, who’d complained of heavy and painful periods for years. Finally, an MRI for a hamstring injury happened to catch her fibroids, too.

Fortunately, once fibroids are located, there are several treatment options to alleviate symptoms, remove fibroids, or both. Many runners, including Nukuri and Adamo, describe the results as transformative, both for their physical and mental health. Post-surgery, “I feel like a brand-new person,” says Adamo, now 48 and living in Miami.

What are fibroids, and how can they affect your running?

Your uterus is a giant muscle; it expands to hold a baby and contracts each month to expel the lining and also when you give birth, says Dr. Sara Jane Pieper, a runner and medical director of gynecology at Intermountain Healthcare in Murray, Utah.

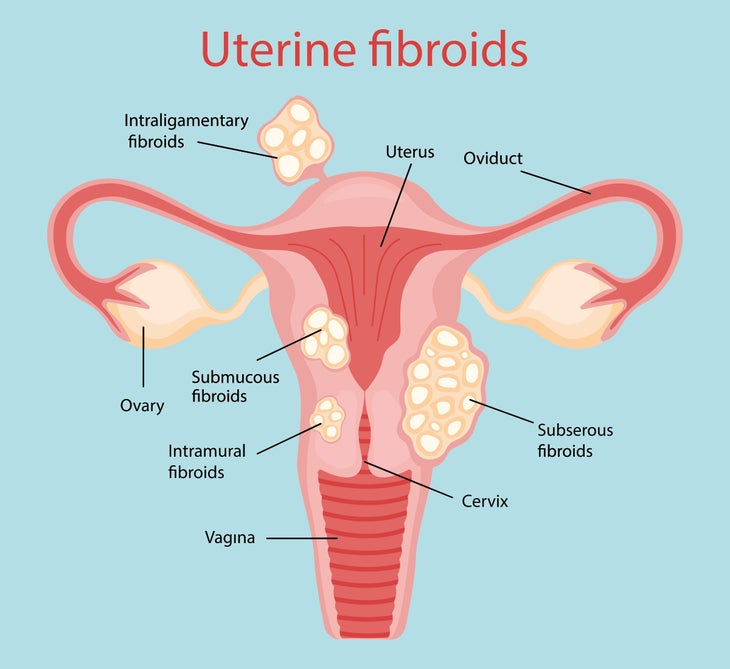

Sometimes, a gene activates in a single muscle cell, causing it to replicate, Dr. Wright says. The result is a fibroid, a ball or whorl of muscle that can grow within the wall of the uterus, bulge into its cavity, or protrude outside of the organ.

Fibroids are fairly hard—the consistency of a softball—and range in size. Some are so small they’re invisible. Others are large enough to distort the size and shape of the uterus. (Adamo, for instance, had three large ones ranging from golf ball– to orange-sized, along with many smaller ones.)

The symptoms they cause vary depending on their size and location, Dr. Pieper says. For reasons experts don’t completely understand, fibroids that grow into the uterine cavity are more likely to cause heavier or prolonged bleeding.

Extended periods tipped off marathoner Kristina Zahniser to her fibroids. By her early 40s, the Dublin, Ohio, mother of three began to notice her periods were heavier and longer, not to mention more painful. Last year, when she went in for her annual gynecologic exam, she was in the middle of a period that had lasted almost two weeks.

Such heavy blood loss can also lead to sluggishness, fatigue, and anemia, which affected Canton, Massachusetts–based runner Michelle Dixon. Dixon, now 55, first learned she had fibroids when she got an ultrasound during her first pregnancy, but they didn’t cause symptoms until about two years after her second son was born.

At that point, “a switch flipped,” she says; her periods got heavier, her cramps so severe she doubled over in pain, and her energy flagged. She’d been running half marathons, but now, she struggled to make it through three miles.

She was diagnosed with, and treated for, iron deficiency anemia. But when that didn’t work, her doctor did another scan, and saw that her fibroids had grown. Instead of racing her fall schedule of 5Ks, 10-milers, and half marathons in 2015, she had surgery.

RELATED: The Female Runner’s Complete Guide to Iron

Besides irregular periods, fibroids that extend outward can push on other organs, causing pressure and other problems doctors refer to as “bulk” symptoms. You might feel pain or pressure in your pelvis, and fibroids can even fill enough space that you can’t eat as much, potentially compromising your fueling, Dr. Pieper says.

Bloating or a bulging, distended abdomen are also frequent. Nukuri recalls that, during the 2019 Prague Marathon, she was on her period and could barely fit in her racing uniform. “I looked like I could have been six months pregnant,” she says.

Plus, your core and pelvic floor muscles are critical to your running performance, says Dr. Tamara Perry, a marathoner and obstetrician/gynecologist at Advanced Women’s Health of Chicago. If fibroids interfere with the way those muscles engage, you may even notice differences in your running mechanics.

RELATED: The Runner’s Guide to Pelvic Floor Pain

Fibroids often squeeze the bowels or bladder. You might also get constipated, have pain with bowel movements, or incontinence (the inability to hold urine) as well as urgency.

Like Dixon, runner Laura Smith first learned she had a fibroid accidentally, during an ultrasound to find a misplaced IUD. About a year later, she had another ultrasound for a similar purpose, which revealed the fibroid had grown.

Around the same time, Smith noticed a new interruption on her regular runs from her home in Sheffield, Massachusetts. “I couldn’t go an entire mile without having to go to the bathroom,” she says. “Or I would stop with my dog, wouldn’t even know I had to pee, and just pee there standing on the street. It was super embarrassing and uncomfortable.”

Her doctor determined the fibroid pushing down on her bladder was the culprit, and Smith is now on medication to alleviate her symptoms.

How are fibroids diagnosed and treated?

Although the symptoms are somewhat vague—meaning they could be caused by many different health problems—diagnosing fibroids is relatively simple. Most doctors start with an ultrasound, which can quickly confirm fibroids’ presence.

Sometimes, once they’re spotted, you’ll also get an MRI. Fibroids are so dense sound waves can’t always penetrate them completely; magnetic resonance image paints a clearer picture of their size and location, Dr. Pieper says.

Treatment options are highly individual and depend on such factors as where your fibroids are, how many you have, and your goals and priorities—including whether you plan to have children in the future, Dr. Perry says. You and your doctor should discuss and decide together, based on what’s most important to you.

One option, according to Dr. Wright, is expectant management: Essentially, keeping an eye on the fibroids and not intervening unless symptoms worsen. Many women close to menopause choose to wait it out, especially if their symptoms aren’t severe.

Estrogen is thought to fuel the growth of fibroids, says Anna Camille Moreno, a women’s health and menopause specialist at Duke University Medical Center. So when you reach menopause and hormone levels drop, fibroids often shrink and get softer.

If bleeding represents your main symptom, there are several ways to cope without removing the fibroids, including:

- Taking 400 to 600 milligrams of ibuprofen every six to eight hours—starting a few days before your period and through the heaviest days of bleeding. This not only relieves pain, but also reduces blood flow, Dr. Perry says.

- Medication called tranexamic acid, which slows the breakdown of blood clots

- Oral contraceptives and hormonal IUDs (like the Mirena), which thin the lining of your uterus, helping to regulate your cycle and reduce or even eliminate bleeding, Moreno says.

Those options might ease bleeding and cramping, but don’t shrink the fibroids or address bulk symptoms, including constipation and incontinence. For those, your options include medications called GnRH agonists and an array of surgeries and procedures.

GnRH agonists block the production of estrogen and progesterone, putting you into temporary menopause. Thanks to side effects like hot flashes and bone loss, they’re not a long-term solution. But, they may bridge you to menopause or take you through an important training cycle, Dr. Pieper says.

It’s one of these drugs, called Lupron, that Smith is taking. The 48-year-old turned down surgery, for the moment—she’s maintaining an 8-year running streak and doesn’t want the downtime. Four months into her six-month course on the drug, she says, it’s been working; she can make it a little bit farther without a pit stop, and feels less anxious about it.

Procedures that can either shrink or remove fibroids include:

- Hysteroscopy, in which fibroids inside the uterus are removed through small tools inserted into your vagina

- Myomectomy, or taking the fibroids out through an incision in your uterus. This can be either laparascopically—using small incisions and slender instruments—or through a larger cut in your abdomen

- Radiofrequency ablation, which burns fibroids with radiofrequency energy

- Endometrial ablation, a similar procedure that removes the entire lining of your uterus

- High intensity focused ultrasound, which uses sound waves for a similar purpose

- Uterine artery embolization, where radiologists inject small particles that block blood flow to your uterus and your fibroids, shrinking them

- Hysterectomy, or removal of your uterus. For women with a high fibroid burden—meaning many tumors—this may be the best choice.

Some treatments, such as hysteroscopy or myomectomy, preserve your fertility. Others, including uterine artery embolization, endometrial ablation, and hysterectomy, make a future pregnancy difficult or impossible.

And with any procedure except a hysterectomy, your fibroids may grow back—this happens between 30 and 40 percent of the time, Dr. Wright says. Doctors can’t always predict who will be affected, but they can make some guesses.

In some cases, an MRI will reveal multiple tumors of various sizes throughout the uterine muscle. “I call it growing a garden of fibroids,” Dr. Pieper says. “Those people probably also have little baby fibroids, little seedlings that are ready to grow. We know that if we take out larger fibroids, more will likely replace them.”

That’s exactly what happened to Adamo. She had a myomectomy at age 30, because she knew she wanted a family. When she did get pregnant with her daughter, who’s now 14, her ultrasounds showed that she still had fibroids.

However, they didn’t cause any other problems until three or four years ago. She first noticed her symptoms on the run: She’d have to stop frequently to pee, and often leaked blood if she ran on certain days of her period.

She went back to the doctor, and learned she once again had three large fibroids, along with a uterus full of smaller tumors distorting its shape and putting pressure on her other organs. At that point, her options included embolization and a hysterectomy.

Adamo deliberated carefully: “Even though at this point, we knew we were not having more kids, I think the thought of losing my uterus was too heavy for me,” she says. So, she scheduled an embolization.

But the pandemic pushed back the procedure. In the meantime, her symptoms worsened. She spent most of her period exhausted and in pain, and packed extra clothes and sanitary supplies everywhere she went. She asked the administration at the school where she’s a third-grade teacher for a classroom with a restroom attached, so she wouldn’t leave her students unattended on her frequent visits.

Running became increasingly difficult; she once made it a half-mile away from home before her bleeding was nearly uncontrollable. Slowly, she walked back, conscious of others’ stares. “I looked like I had been stabbed,” she says.

When is it time to seek treatment, and what can runners expect when they do?

Not every heavy period will be quite so obvious; some people’s symptoms develop so slowly they may not realize anything’s wrong, Dr. Wright says. “For athletes of all kinds, there’s kind of a double-edged sword,” she says. “They’re more in tune with their bodies, but they’re also more used to pain. They can sometimes write off certain sensations as part of muscle strain or day-to-day wear from what they’re doing.”

Tracking your cycle can help you identify changes, and anything that’s out of the ordinary for you can signal a problem, according to Dr. Perry. Generally, a heavy flow means changing your pad or tampon more than once per hour, having regular accidents, or arranging your life around your cycle.

RELATED: 7 Good Reasons for Runners to Start Tracking Their Periods

“If a patient tells me, well, the first two days of my period, I work from home because I can’t get to the bathroom fast enough without staining my clothes,” Dr. Wright says, “that’s not normal.” Also talk to your doctor if your period lasts longer than seven days, or if it’s accompanied by symptoms like fatigue and an inability to make it through a run, says Dr. Pieper.

Take these signs seriously, and find a doctor who does, too. If you feel like the first medical professional you see is dismissive, seek a second or third opinion until you find one that isn’t, Dr. Wright suggests.

Nukuri agrees; after her hamstring MRI incidentally revealed her fibroids, a doctor recommended a pelvic ultrasound to see them more clearly. “I was thinking, how come nobody suggested this 10 years ago? I was pretty angry,” she says. “Every time I talk to a woman who’s complaining about their periods, I tell them to go get an ultrasound.”

Depending on your treatment choice, you may have to take some time off running to recover. If you’re having a myomectomy or hysterectomy, Dr. Pieper and Dr. Wright both recommend trying to find a surgeon who will do a minimally invasive procedure, which speeds your recovery time.

“Most patients are a candidate for minimally invasive options, they just have to find a center,” Dr. Wright says. “Our division, since we specialize in this, we’re able to do about 90 percent of the surgeries for fibroids in a minimally invasive fashion.”

But regardless of the type of procedure you have, the good news is that afterward, you’re likely to experience significant relief—including while running.

After completing the Boston Marathon last September, Zahniser had an endometrial ablation right before Christmas. She was back to running within a week, and has had only light spotting since. Dixon had a hysterectomy, and after her recovery, she’s running stronger than ever.

“To use the phrase life-changing may sound overly dramatic, but it really was,” Dixon says. “Once you get your legs moving again, you’re good. And I’ve honestly never looked back.”

As for Adamo, when the pandemic delayed her embolization, she reconsidered her options. “During that time, I realized that I was suffering so much, and I didn’t need to be,” she says. Her doctor told her the choice was hers, but an embolization might not bring complete relief, and she still had several years before menopause.

So last October, she had a hysterectomy. Two weeks later, she was cleared to run, and began easing back in. “While running, I just feel better. I don’t feel as heavy or and lethargic,” she says. “The word that comes to mind is bouncier. I’m just not weighted down with it anymore.”

And on March 6, she completed her first race back, the Baptist Health 305 Half Marathon. “It was 31 minutes longer than my PR, but I have never felt better running a race,” she says. And that, rather than time, was her goal. “I wanted to complete it before the six-month mark [after surgery], just to prove to myself that I could bounce back and be better than I was before.”