Products You May Like

As we sit in the midst of what once again feels like the receding of the COVID-19 pandemic, I find myself feeling guardedly optimistic. The Omicron variant swept through much of the population and displaced the more dangerous variants from the scene, leaving behind a degree of herd immunity enhanced by vaccination. While we are seeing increased case rates in Europe from an even more infectious version of Omicron, that has not been associated with increased rates of hospitalization or death. Early indicators are that another wave of infection may soon break upon North America, and even if it is not associated with a significant burden of mortality, we know COVID brings with it a fair amount of morbidity.

Since this virus first appeared, the learning curve for the medical community has been steep and there is still far more that we do not know than we do about this wily adversary. As an athlete, coach, and medical provider, two specific questions related to COVID remain of the utmost interest:

- How and when is it safe to return to training after a COVID infection?

- What are the long-term consequences of a COVID infection?

The answer to these questions are very much inter-related and though we have more than two years of experience with this disease, we still do not have a full understanding to be able to answer them completely satisfactorily.

A recent paper from the University of Massachusetts in the Journal of Applied Physiology provided an excellent overview of the current state of understanding on this subject. Alas, that understanding is that while there has been a lot of published research it has left a lot more questions.

What is Long COVID?

Long-term symptoms that persist after the acute infection has cleared is referred to as “long-COVID.” In studies of patients who were hospitalized with the disease, as many as two-thirds of patients described symptoms persisting for months after infection, with fatigue and shortness of breath being the most common. Up to half of these patients experience symptoms a full year after hospitalization, though most report improvement after six months, suggesting that recovery over time does occur. Even for those with mild disease, more than one-third of patients report persistent symptoms for several weeks after illness.

RELATED: 18 Months After COVID-19, This Ultrarunner is Still Struggling

Muscle weakness is also an issue reported by patients who have been hospitalized with COVID and is one of the more important symptoms of long COVID. Up to 80% of patients have demonstrable weakness on structured strength testing 20 days post-hospital discharge and as many as one-quarter of older patients will still be demonstrably weak up to three months later.

Previous studies have focused on the unusually high prevalence of neurological symptoms, such as insomnia and anxiety, and given the importance of sleep on exercise performance, this aspect of long-COVID may be quite consequential for athletes. Dr. Corinna Serviente, a post-doctoral fellow and one of the authors of the paper from UMass, explained: “It’s hard to tease apart the insomnia and the physical fatigue and the muscle weakness that these patients may be experiencing as a consequence [of long-COVID] in order to know what is really the issue. The end result is that people’s performances are hurt.”

While the pulmonary manifestations of acute COVID are well-known to most and remain the primary means by which the virus causes morbidity and mortality in the acute phase, for athletes who recover from the illness the effects that the virus has on the heart are actually the issues that cause the most concern.

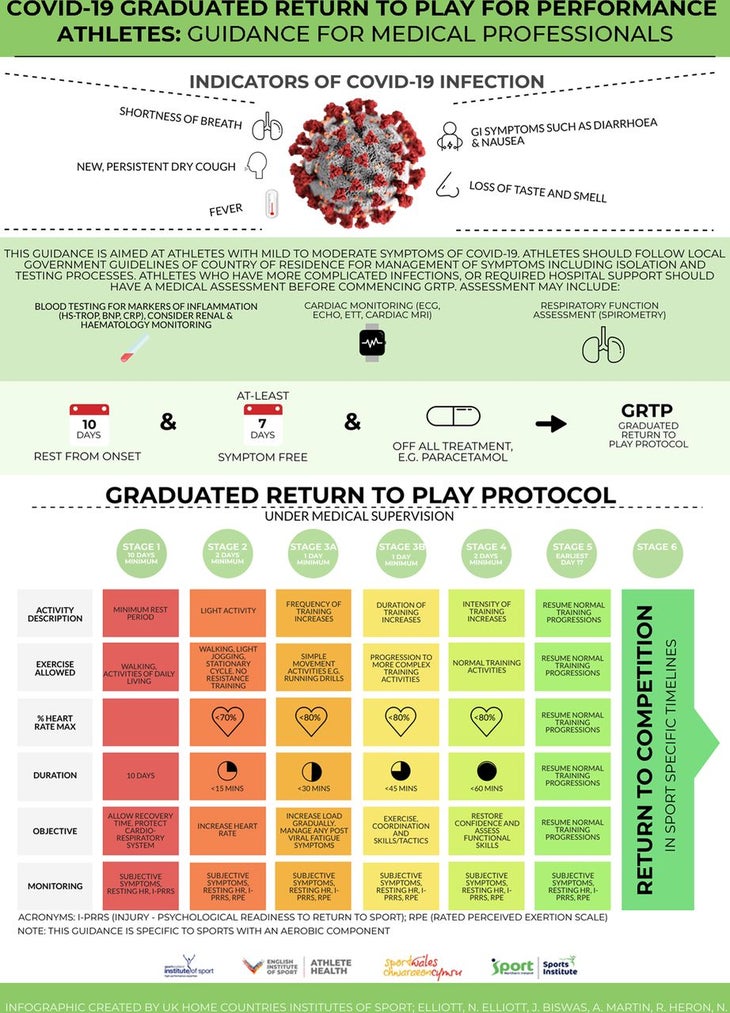

Studies on young mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic athletes have shown that as many as half show signs of myocardial damage during the convalescent period. This is what has led to the very conservative return to training guidelines published by several cardiology societies and the more progressive but still cautious guidelines published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

A co-author of the UMass review article, Gwenael Layec is an associate professor of kinesiology. He told me that one of the major concerns about COVID’s effects on the heart is “the lack of the ability of cardiac muscle to recover from injury.” He said, “The formation of scar tissue within the heart muscle may very well be permanent and while in the short-term for a young athlete it may not be important, as that person ages once they get into their 50s and 60s will that damage make them more susceptible to cardiac events? We just don’t know.”

RELATED: What Experts Say About Running After COVID-19

“In terms of myocarditis, we aren’t seeing a lot of athletes collapsing on the field after having COVID and going out and exercising,” Serviente said. “I am much more worried about what the long-term consequences of this are and that is something that we just don’t know yet.”

Serviente and Layec’s concerns are based in part on a growing body of evidence that suggests COVID also affects the blood vessels, making them stiffer and less responsive to endogenous substances that would normally make them relax. When combined with possible cardiac dysfunction, stiffer blood vessels can make things potentially much worse, especially in an athlete who is training hard. “I worry that if a young athlete is showing signs of vascular injury and dysfunction after COVID, what does that mean for them 10 or 20 years down the road? Are they then going to be at risk for early onset cardiovascular disease?” Serviente said.

While long-term cardiac issues are very concerning but as yet undefined, one thing that is well understood is the impact on overall exercise performance from and after a COVID infection. In patients who had been hospitalized with COVID, peak cycling power at time of discharge was half that of control subjects and only rose to 90% of age-predicted normal values three months later. Values for VO2 max were similarly affected. Layec concedes that in this area there is no available data for people who had only a mild version of the illness and did not require hospitalization, but he said, “This is not a mild disease; it’s not like a cold. Even in those who are not hospitalized it takes quite a while to recover and get back to their pre-COVID ability.”

This lower exercise tolerance after COVID infection is thought to be related to altered handling of oxygen at the cellular level and the time for recovery and degree for reversion to normal is still not known.

What Should Runners Do?

All of this reinforces the need to prevent COVID infection in the first place. The waning numbers of cases obviously helps with this, but there is no doubt that the best defense against long COVID remains vaccination. Vaccines have now been shown not just to prevent serious illness and death, but also to reduce the likelihood of long COVID in those who do get breakthrough infections.

Two separate studies, one from the UK and one from Israel, have supported the idea that vaccination decreases long COVID by more than half in those who do become infected. There is even a suggestion that the cause of long COVID is continued replication of the virus at low levels in certain cells and that vaccination in previously unvaccinated individuals may reduce long COVID symptoms by stamping out this low grade viral propagation. “We have some experience with patients like this and anecdotally they report that vaccination does provide some improvement for maybe a couple of weeks but thus far we have not seen sustained long-term benefits,” Serviente said. This is obviously an area of ongoing research.

However this pandemic proceeds from this point forward, athletes need to remain vigilant and respectful of a virus that retains the ability to do so much more than just cause a transient respiratory illness. While we can hope that the current trend will continue and the days of large waves of infection are truly behind us, even in that scenario COVID is here to stay in some form or another, and should you become infected, being aware of the potential for long-term symptoms can prepare you to be ready to modify your approach to training and recovery.