Products You May Like

Get access to everything we publish when you

sign up for Outside+.

Carbohydrates are one of three types of macronutrients used by the body—the other two being fat and protein. Carbohydrates come in many forms, including vegetables, fruits, whole grains, pasta, bread, milk/milk products, sports drinks, and sports nutrition supplements such as gels, chews, and drinks. In their most basic form, carbohydrates are glucose, and this is converted by your body into energy—providing four calories per gram (protein also provides four calories per gram, while fat provides nine). There are many forms of carbohydrates:

- Monosaccharides

- Disaccharides

- Oligosaccharides

- Polysaccharides

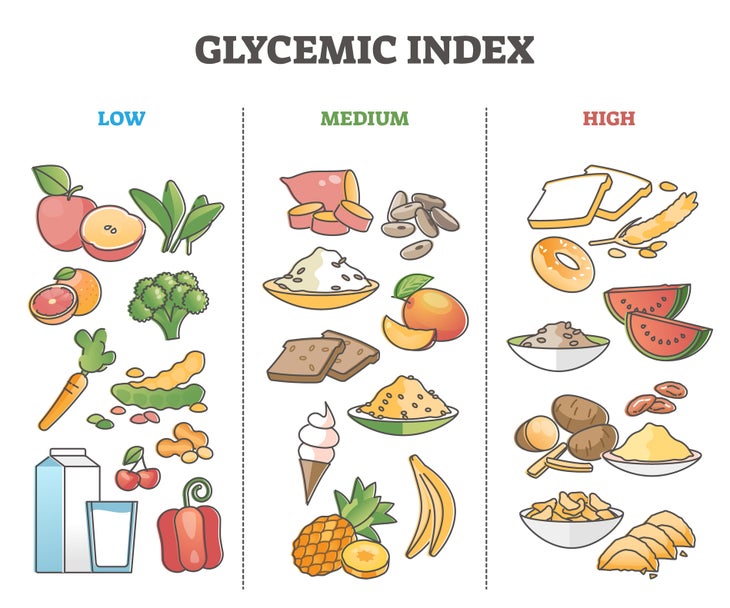

Think of mono- and disaccharides as simple carbs, with oligosaccharides and polysaccharides as complex carbohydrates. The simpler a carb is, the quicker it will be broken down and used by the body as energy. Simple carbs will result in a rapid rise in blood glucose and insulin secretion from the pancreas; complex carbohydrates take longer to digest and will result in a steadier rise in blood glucose. Neither is “good” nor “bad” when viewed in the correct context for the purpose of consumption.

RELATED: Your Complete Runner’s Guide to Carbohydrates

What is carb loading?

Carb loading involves an athlete topping up their muscle, blood, and liver glycogen (carbohydrate) stores by consuming a very high amount of carbohydrates in the days leading up to a race. Carb loading is a widely accepted part of endurance sports preparation and usually is done going into any event where the majority of time is going to be at a pace that will require the body to utilize carbohydrates as its primary fuel source (this is typically anything above 65-70% of your VO2 max). This topping up of carbs—or “super compensation”—results in glycogen stores being up to 100% above the normal storage of glycogen.

The Swedes were the first to report on the concept of carb loading in 1967, undertaking research that highlighted the body’s ability to super compensate with carbohydrates to improve muscle and liver glycogen stores. Unfortunately, their particular approach required three days of exhaustive exercise combined with three days of high-carbohydrate fueling, which is hardly the pre-race taper many of us adhere to now.

Thankfully, subsequent research demonstrated similar benefits from just three days of light exercise and three days of increased carbohydrate fueling (where 70% of your total energy intake is carbohydrate). Fast forward to the present day and there are a couple of relevant, research-based carb-loading protocols that aim to boost your liver and muscle glycogen by ~80-90% before a key event.

A single day of a high-carbohydrate diet, using grams of carbohydrate per kg of bodyweight to calculate your needs, could be used to increase muscle glycogen stores by 90%. Alternatively, a day of short, high-intensity training (literally a few minutes) followed by a day of light exercise then complete rest, combined with significant amounts of high glycemic foods and fluids the day before a race, can also increase glycogen levels by more than 80%. High glycemic foods are those that are ranked highly on the glycemic index: they are foods that are rapidly digested and absorbed and cause a sharp rise in blood sugar (e.g., white rice, white bread, white pasta, and pretzels).

Myths, misconceptions, and common carb mistakes

One of the biggest mistakes athletes often make when approaching carb loading is failing to practice it in training. Ideally, a runner will practice carb loading going into race simulation workouts a few times before race week. This allows you to assess your reaction to the higher carbs, practice eating the actual prescribed carbohydrate amounts, and decide which foods are best tolerated.

Practicing the carb load is absolutely crucial, but doing dry runs of the pre-race breakfast and the in-session race fueling is equally as important. Rehearsing these strategies will provide familiarity and confidence that a fueling strategy is on point when it comes to race day. Skipping this can be an athlete’s greatest undoing during a race.

RELATED: What to Eat on Race Day (And How to Make Sure Your Fuel Works for You)

Female athletes and carb-loading

For women, there is a dearth of research investigating carb loading related to race-like conditions. The majority of studies have focused on the percentage of energy intake (i.e., 70-75% of total energy intake) as the measure of carb loading. However, the studies did not determine whether the total energy consumed on a daily basis actually met the demands of training and racing. Therefore, despite eating 70% carbs as a percentage of their daily nutrition intake, the total grams per kilogram of body weight may not have been sufficient to load the body.

There are a few studies that have investigated loading in women using a high enough amount (e.g., 8-10g/kg/bodyweight/day) and found they are able to increase glycogen stores. Women need to load in relation to their body mass and consume high amounts of carbohydrates in order to boost glycogen stores.

Another consideration is the menstrual cycle phase and how it impacts carb loading. Women appear to have a greater capacity to store glycogen during the luteal phase (the ~14 days after ovulation) compared to the follicular phase (the first day of bleeding through to ovulation).

While more research is required, it is important to note that what works for one woman will not necessarily work well for another. Working with your coach and a nutritionist to test what you are able to comfortably consume is of utmost importance.

RELATED: 360 YOU: You Can Probably Benefit From Seeing a Dietitian (Here’s What to Expect)

Carb loading versus high-carb fueling

Overall, it is important to remember that muscle glycogen levels alone do not determine fatigue. The consumption of carbs results in stable blood glucose levels, and if the intake is high enough, it spares liver glycogen. As you improve your endurance capacity with training, there is an improved oxidation rate of blood glucose and improved economy for fueling. In short, as you get fitter you become a far more efficient fueling machine.

This is where the concept of high-carbohydrate fueling becomes an additional and important strategy. This strategy should be practiced in training and employed during your race. An athlete’s ability to consume high amounts of carbohydrates relative to their body mass during a race will result in sustained carbohydrate oxidation (burning of carbs as fuel) and, ultimately, sustained power and speed.

Make carbs work for you

The importance of carbohydrates for racing is unequivocal. As athletes push their bodies above that barrier around 60-70% of VO2max, the body begins to switch from predominantly using fat for fuel to carbohydrates. This is particularly apparent as the exercise duration extends beyond 90 minutes, which marathons do. Not only does the use of carbohydrates as a fuel source become more prominent, but also the energy cost of using carbohydrates as a fuel source is more than that of fat. In other words, when you want to go fast and go long, you need carbohydrates—and plenty of them.

Simple and familiar foods are key in the lead up to a race. It’s all about fueling for a purpose, rather than culinary excellence. Here are five top tips for race week nutrition, as well as a carb-loading menu for the 24 hours pre-race.

RELATED: The 10 Best Carbohydrate Sources For Runners

Top tips for carbing up race week

Begin high carbohydrate consumption a minimum of 24 hours before any race that’s longer than 90 minutes.

Optimal loading would be to increase carbohydrate intake 48 hours in advance, consuming at least 6-8g per kg of bodyweight per day.

Consume a combination of high-glycemic foods and fluids to reach the recommended intake levels.

Drinking some of the carbs can help reduce that stuffed feeling. Suggested drinks include fruit juice, chocolate milk, and energy drinks.

High glycemic foods are key.

These include white bread/bagels, white pasta, white rice, white potatoes, breakfast cereals such as Rice Krispies or cornflakes, pancakes, potatoes, rice crackers, fruits such as raisins, bananas, mangoes, pineapple, and sweetened dairy products such as fruit yogurts.

Reduce total fiber intake in the 24-48 hours leading into a race to minimize content in the intestines.

Limit leafy and fibrous vegetables to 1-2 servings in total.

On race morning, aim to consume a meal approximately two to three hours prior to the start time of about 80-100g carbs and containing fiber.

Fiber helps protect the lining of the gut from a heat-stress injury. Carbohydrates also play a major role in this. Suggested foods include oatmeal (cooked or overnight oats), whole wheat toast/bread, banana, and yogurt.

Scott Tindal is a performance nutrition coach with 20 years of experience working with pro and amateur athletes. He has a Masters degree in sports medicine and a post-graduate diploma in performance nutrition. He is the co-founder of FuelIn, an app-based personalized nutrition coaching program.