Products You May Like

Get full access to Outside Learn, our online education hub featuring in-depth fitness, nutrition, and adventure courses and more than 2,000 instructional videos when you sign up for Outside+

Sign up for Outside+ today.

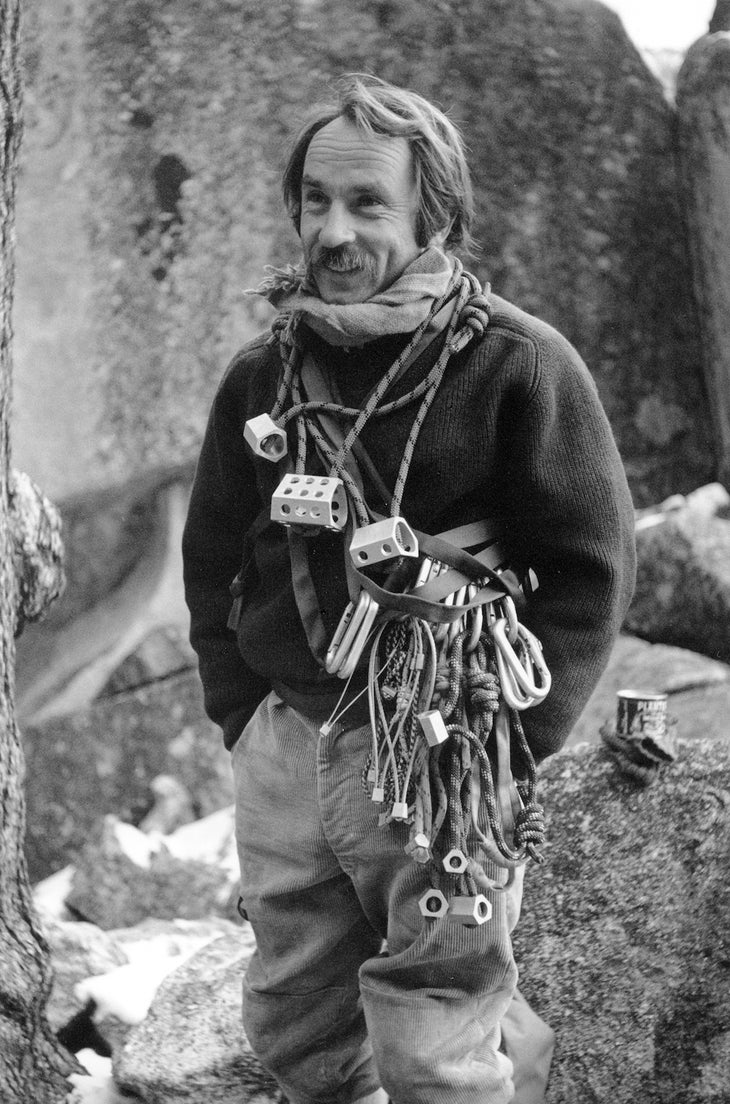

On the eve of its 50th anniversary, Patagonia, one of the nation’s most innovative and ethical corporations, is under new ownership.

The outdoor apparel maker, founded in 1973 by Yvon Chouinard and run by the Chouinard family since its inception, announced today that the company has restructured, with control of the business transferred to two new private entities: a trust that owns all of Patagonia’s voting stock and a nonprofit called the Holdfast Collective that owns all nonvoting stock and oversees Patagonia’s environmental work, which is set to expand sharply.

Effective immediately, 100 percent of Patagonia’s earnings not reinvested in the business will be distributed to the Holdfast Collective to help “protect nature and biodiversity, support thriving communities, and fight the environmental crisis,” according to a press release. The company has for years donated 1 percent of its sales to grassroots and environmental causes, but this shift will increase that figure dramatically. The estimated charitable outlay of the new company will be roughly $100 million a year.

Ryan Gellert, the company’s current CEO, will remain in place as chief executive, and the Chouinard family will maintain heavy involvement, sitting on the company’s board, guiding the trust that owns the voting stock, and overseeing the philanthropic efforts of the Holdfast Collective. The company’s headquarters will remain in Ventura, California.

Creating a New Corporate Model

Chouinard, 83, started planning the corporate restructuring two years ago. Searching for a way to increase the company’s positive impact on the environment, he considered several options, which he outlined in a letter published today.

“One option was to sell Patagonia and donate all the money,” he wrote. “But we couldn’t be sure a new owner would maintain our values or keep our team of people around the world employed. Another path was to take the company public. What a disaster that would have been. Even public companies with good intentions are under too much pressure to create short-term gain at the expense of long-term vitality and responsibility. Truth be told, there were no good options available. So, we created our own.”

Gellert and a small team of Patagonia executives were tasked with creating the new business model. Under the cover of a project code name—Chacabuco, a nod to a fishing location in Chile—they began brainstorming solutions in mid-2020. Other than selling the company or taking it public, they considered transforming it into a nonprofit or an employee-owned co-op, like REI. Eventually, they landed on the current plan.

“Two years ago, the Chouinard family challenged a few of us to develop a new structure with two central goals,” Gellert wrote in a release today. “They wanted us to both protect the purpose of the business and immediately and perpetually release more funding to fight the environmental crisis. We believe this new structure delivers on both.”

That new structure required the Chouinard family—Yvon, his wife Malinda, and their children, Claire and Fletcher—to donate all their company shares to the newly established trust, officially called the Patagonia Purpose Trust, which will cost them about $17.5 million in gift taxes.

As for the Holdfast Collective, it’s structured as a 501(c)(4), which the company said it chose for the flexibility of the legal entity. 501(c)(4)s are allowed to make unlimited donations to political causes, meaning the Chouinards get no tax benefit for money that flows to the entity. Patagonia’s head of communications and public policy, Corley Kenna, said to expect the Holdfast Collective to distribute its funds in wide and varied ways: in grants to organizations addressing the root causes of the climate crisis, investments in land and water protection, and support for stronger government policies to protect the planet, to name a few.

To anyone who doubts the company’s willingness to pioneer new types of aggressive corporate advocacy, Kenna also urged people to remember that this is the same brand that called on its community to “vote the assholes out” during the Trump administration, and joined with Indigenous communities and grassroots groups in Utah to sue that same administration for its shrinking of Bears Ears National Monument.

The corporate restructuring—especially the transfer of all nonvoting stock to a nonprofit—was only possible because Patagonia doesn’t offer employee stock options. In his book The Responsible Company, published a decade ago, Chouinard outlined his concerns about employee and public ownership, arguing that wider control of the company’s shares might have prevented a change like the one announced today.

“[We] are concerned that, with shares more broadly distributed, the company would become overly cautious about undertaking risks in the pursuit of its environmental goals,” Chouinard wrote in 2012. “So that Patagonia can continue to push back the boundaries of what business considers possible, [we] are willing to undertake risks that might give pause to broader ownership, even of employees committed to reducing environmental impact.”

Announcing the Changes

The company shared the news with employees in a virtual town hall this morning. In its announcement, Patagonia pointed out that Chouinard is in good health, but that he “wanted to have a plan in place for the future of the company and the future of the planet,” according to Kristine McDivitt Tompkins, a board member.

“The current system of capitalism has made its gains at an enormous cost,” wrote Charles Conn, Patagonia’s board chair, in a release today. “The world is literally on fire. Companies that create the next model of capitalism through deep commitment to purpose will attract more investment, better employees, and deeper customer loyalty. They are the future of business if we want to build a better world, and that future starts with what Yvon is doing now.”

True to its talent for attractively marketing its environmental efforts, Patagonia has devised a pair of slogans that sum up the company’s retooled structure. Instead of going public, the brand has “gone purpose.” And because the Patagonia Purpose Trust is the business’s controlling shareholder and must adhere to the company’s environmental mission, the brand now claims that Earth is its “only shareholder.”

The claim may be less exaggerated than it sounds. The Patagonia Purpose Trust has no individual beneficiaries and the stock it controls can never be sold, meaning, according to deputy general counsel Greg Curtis, “there is no financial incentive, or structural opportunity, for any drift in this trust’s purpose.” An unnamed independent protector has also been designated to “monitor and enforce” the mission of the trust.

“It’s been a half-century since we began our experiment in responsible business,” Chouinard wrote today, addressing the company’s roughly 3,500 employees. “If we have any hope of a thriving planet 50 years from now, it demands all of us doing all we can with the resources we have. As the business leader I never wanted to be, I am doing my part. Instead of extracting value from nature and transforming it into wealth, we are using the wealth Patagonia creates to protect the source. We’re making Earth our only shareholder. I am dead serious about saving this planet.”