Products You May Like

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members!

Download the app.

You can’t hike the same trail twice—literally. They might give off an air of permanence, but our favorite parks, paths, and campgrounds are constantly in flux. From policy changes to park expansion and trail development to area preservation, some of our favorite sites look and feel very different than they did five decades ago. There’s no better way to show these changes than cracking open the photo books. Here’s how our favorite wilderness areas and national parks changed throughout the years.

Glacier National Park

Archive Photo: 1973

By the mid-1970s, nearly 1.5 million visitors entered Glacier National Park each year, with most arriving during June, July, and August, nearly double the number that had visited in the 1960s. The biggest hurdle the park faced was figuring out a balance between “resource protection and public utilization.” Adding extra pressure, in September 1974, the United Nations selected Glacier as one of its “World Biosphere Reserves.” That designation singled it out as an area worth preserving for future ecological research, as a natural ecosystem for comparison with modified areas, and as a candidate for the future Global Environmental Monitoring program.

Meanwhile, during the 1970s, the national park fielded proposals for invasive natural resource use all based on economic expediency. These proposals included damming the North Fork of the Flathead River, clear-cutting forests within the park, and allowing coal mining near park lands. These not only would affect the visual beauty of the park itself but cause severe pollution as well. They never came to pass, but even today, politicians continue to create proposals that spotlight financial gain instead of what’s best for the park.

Archive Photo: 1975

Granite Park Trail, a loop trek from Granite Park Chalet that gains 2,450 feet in 4.2 miles, is one of the most popular trails in Glacier National Park. Before 2003, it was heavily wooded, but a lightning-ignited wildfire burned more than 19,000 acres and led to exposed vistas of nearby mountains. Because this area is still regenerating from the destruction, you’ll find extensive undergrowth and thousands of wildflowers.

Modern Day

Between the years 1966 and 2015, the total surface area of the three dozen glaciers in GNP decreased by about 34 percent, and every glacier’s surface was smaller in 2015 than it was in 1966. According to the park’s website, “Glacier National Park is warming at nearly two times the global average and the impacts are already being felt by park visitors.”

Glacier doesn’t have a reputation as a hot place, but increasingly hot days are hazardous for under-prepared hikers. Days over 90ºF were once rare, but in 2020 alone, West Glacier experienced 11 days that hot. Trails such as the Granite Park Trail (also known as Loop Trail) and the Highline Trail are shadeless and have limited access to water, which can pose a danger to unprepared trekkers.

Grand Canyon

Archive Photo: 1974

The 1970s were a time of booming growth and development for Grand Canyon National Park. Backpacking became a popular reason to explore the national park, which crowded the established trails and campgrounds. According to the parks service, some summer nights, there would be 800 to 1,000 campers in Phantom Ranch, a campsite that comfortably sleeps only 75. Because the growth in visitation and recreation was so drastic, the park created a backcountry office, a reservation system, and its first backcountry management plan in 1974.

The following year, President Gerald Ford signed an act that combined the Grand Canyon with two national monuments and other federal land, which doubled the size of the national park. That same act gave Havasu Canyon back to the Havasupai tribe. Four years later on October 24, 1979, GCNP became an official World Heritage Site.

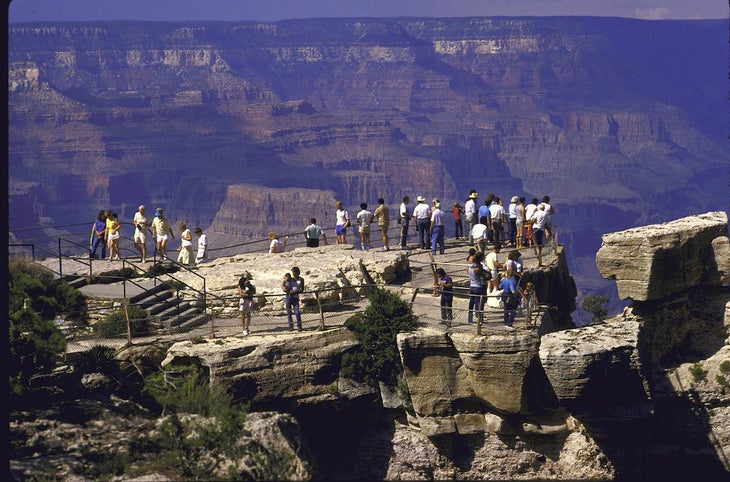

Archive Photo: 1986

Mather Point, a viewpoint along the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, is known for its iconic canyon vistas and proximity to the visitor center. It’s named after Stephen Mather, the first director of the National Park Service and a driving force for the establishment of Grand Canyon National Park. Still to this day, his memorial viewpoint is one of the most popular places to gaze out onto the Grand Canyon from sunrise to sunset.

The park noticed sizable increases in crowds 1986, the year this photo of Mather Point was taken. It was the first year that GCNP reached more than 3 million annual visitors. The park’s visitation rates reached its apex in 2018 with more than 6.3 million visitors.

Modern Day

Most of the park’s visitors today stay above the rim in viewing areas like Mather Point: Only 5 percent of visitors hike into the canyon, and 10 percent of those make it to the river at the bottom. There are enough viewpoints to see the canyon without baking on the hot desert floor.

There are plenty of initiatives in place today to preserve the natural resources and beauty of GCNP. In 2013, BirdLife International named the park as a Globally Important Bird and Biodiversity Area, and in 2019, the park’s centennial, the International Dark-Sky Association designated the Grand Canyon as an International Park Sky Park.

Canyonlands National Park

Archive Photo: 1983

The 1980s were a time marked with growing pains for Canyonlands National Park after the release of the parks General Management Plan (GMP) in 1984. This plan is essentially a mission statement for the park, with resource conditions and visitor experience expectations, which gets updated as conditions change about every 15 to 20 years.

The GMP encountered stiff resistance out of the gate. There were several reasons for this: There was a general distaste for the park’s plan, which combined with Interior Secretary James Watt’s belief that the environment is meant to serve our needs and has no value until we assign it value, and the Sagebrush Rebellion, a movement characterized by hostility between cattle farmers and federal land managers. It doesn’t help that the Energy Department proposed a nuclear waste repository outside the park’s Needles District and a huge tar sands extraction and processing operation just west of the park around that time, too.

In 1989, Canyonlands celebrated its 25th anniversary as a national park. There was a parade in Moab, recognition of the park’s 2 millionth visitor, a canyon country art show, and the release of a new, commemorative logo. In a speech, environmentalist and former Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall said the U.S. should “act like a rich nation instead of a poor one and expand the national parks,” specifically by expanding Canyonlands into the million-acre park he dreamed of.

Modern Day

Today, Canyonlands has remained the same size as it was in 1971 when Congress expanded it to include the Horseshoe Canyon annex: 337,598 acres. There have been swells of activity to push for park expansion since then, but they’ve dulled in recent years. Even though the park hasn’t grown in size, its visitor count has exploded in size each decade. In the 1970s, the annual park crowd count jumped from 33,400 in 1970 to 74,545 in 1979. By 2000, the park was hosting 400,000 visitors each year, and the park reached its record in 2021 with 911,594 visitors.

Ansel Adams Wilderness

Archive Photo: 1996

President Lyndon B. Johnson established the Ansel Adams Wilderness (originally called the Minarets Wilderness) as part of the Wilderness Act in 1964. Twenty years later, Congress renamed the area in memory of Ansel Adams, environmentalist and nature photographer known for his black and white landscape photographs of the Sierra Nevada. Since then, the wilderness area has become famous largely for Banner Peak, the second tallest peak in the Ritter Range of California’s Sierra Nevada, and Thousand Island Lake (both pictured here).

Modern Day

In 1980, four years before Ansel Adams’s death, President Jimmy Carter awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom for “his efforts to preserve this country’s wild and scenic areas, both on film and on earth.” Since then, his namesake wilderness area has become one of the most trodden in the country, with access routes to Yosemite National Park and John Muir and Pacific Crest trails and nearly 30 million people living within a few hours drive.

Today, backpackers looking to explore the Ansel Adams Wilderness and get a view of Thousand Island Lake and Banner Peak need an overnight wilderness permit before hitting the trailhead.