Products You May Like

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members!

Download the app.

Pam Moore was running her third marathon in 2006 when it happened: she cramped up hard. The seasoned athlete had been through a lot of difficult circumstances while training and racing, but she wasn’t prepared for the debilitating, stabbing pain that suddenly announced its presence in her calf. She was only nine miles in, but figured she could tough it out. She pushed on, but soon the cramp spread: first, up from her calf into the then, then across to the other leg.

“It turned into a mental battle of, ‘Can I just make it one more step?’” she recalls. “It was excruciating.”

Ever mindful of her pace, she pushed as much as her body would allow, but “it was just like a death shuffle.” In the end, she says the whole experience was “miserable.”

Ask any endurance athlete who has experienced cramping during training or a race, and they’ll have a story similar to Moore’s. Cramps can be mild or severe, fluttery or full-on, located in one muscle or many. And while one triathlete may swear they’ve found the solution, another might find that solution makes their cramps worse, not better. So why do these happen, and what can science tell us about avoiding this deeply uncomfortable fate?

The basics of cramping

A cramp is a sudden, painful tightening of one or more muscles that can range from mildly annoying to downright debilitating. Cramps come and go, and have retained some mystery about them, as they’ve they’ve proven resistant to a blanket-treatment protocol.

One reason why is because there are many different kinds of cramps, and they’re not all created equal. A pregnancy-related cramp is different from one caused by renal dialysis, which is also different from menstrual cramps, all of which is different from a cramp you feel in the calf during an Ironman. Cramps related to repetitive movement are different from the others, too.

Here, we’re focused on exercise-associated muscle cramps, or EAMCs. These are the kind that creep up on a healthy person who has no underlying conditions, in the latter portion of an intense workout or competition. It’s the kind of cramp that strikes suddenly and leaves you crying in agony and reaching for the affected muscle to massage and stretch the pain away.

Dr. Ronald Maughan, a professor of medical and biological sciences at the University of St. Andrews in the United Kingdom says these types of cramps have plagued workers and athletes for ages, and science has long sought an answer as to why.

“There’s a long history to the study of muscle cramp, and the classic view is that it’s the result of heavy sweating, accompanied by a large intake of water without an appropriate intake of salt.” He clarifies that this is not dehydration, per se, but something “slightly different:” an imbalance between water and electrolytes.

RELATED: Why Women Should Eat Potassium-Rich Food

What we’re getting wrong about electrolytes and cramping

Electrolytes are minerals in the blood that carry an electric charge; they include sodium, magnesium, potassium, calcium, chloride, phosphate, and bicarbonate. Electrolytes are Goldilocks substances – too little of each one can be just as bad as too much. You need to stay balanced with just the right amount of each of these nutrients to perform at your peak.

RELATED: Everything You Need To Know About Electrolytes

Research supporting this view goes back to the early 20th century and studies completed in workers in coal mines, steel mills, and construction sites – all occupations where laborers exert themselves in hot, sometimes very humid environments. Maughan says this body of work has been “fairly clear that the people who were getting cramps, it was more likely to happen in hot weather and it was more likely to happen when people were drinking lots of plain water.” They sweat out lots of salt, and replaced it with just plain water, leading to that disruption in the body’s balance.

Because of this history, the standard advice for most of a century – and the reason why sports drinks like Gatorade exist – has been to stay hydrated, but include salt as well, especially if you’re sweating heavily.

But there may be a lot more to cramping than we’ve been led to believe all these years, says Dr. Kevin Miller, a professor at Texas State University who has studied EAMC extensively. He says there are “some major flaws” with the theory that EAMCs result solely from a fluid and/or electrolyte imbalance.

For example, one of the best ways to stop a cramp in its tracks is to stretch the offending muscle. This nearly always relives the cramp “almost immediately,” Miller says, “and yet, zero fluids or zero electrolytes are added to the body by stretching. There’s a disconnect between purported cause and the effective treatment.”

In addition, Miller says that from about 1997 onward, scientific understanding of cramping has been evolving. “The majority of the science nowadays supports that exercise-associated muscle cramps are related to changes in the central nervous system. Cramping is related to changes in the neurological system stemming from a multitude of factors intermingling like fatigue, pain, and other sources.”

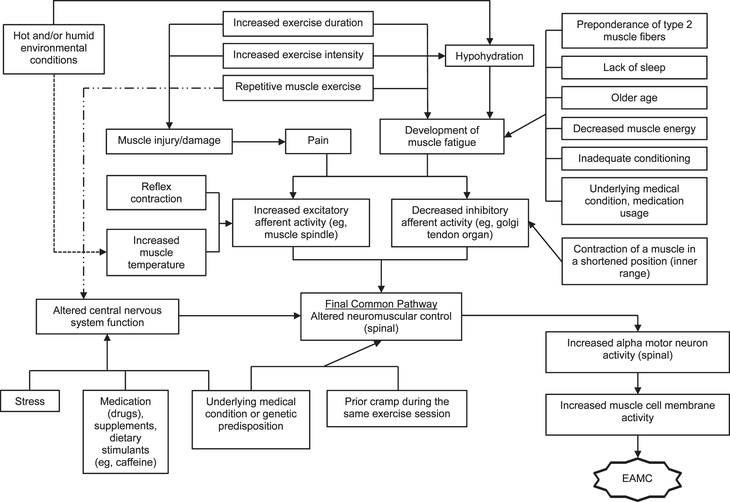

Using that different take on cramps, Miller has developed a multifactorial theory of cramping, most recently in collaboration with Dr. Martin Schwellnus, an exercise scientist from South Africa who’s considered one of the foremost leaders in the field of cramping research. They published a paper in the Journal of Athletic Training in June 2021 “where we propose that cramping is kind of this giant spiderweb of internal and external factors.”

Miller likens this revised understanding of what causes cramping to spaghetti sauce. “Just like there are about 500 different recipes for spaghetti sauce, you might have 500 different recipes for cramping. Your recipe for cramping might be different from my recipe for cramping.”

The ingredients that make up your own special sauce may include pushing too long or too hard, being dehydrated, not having gotten enough sleep the night before, dietary factors, or a variety of other elements. The more ingredients you add to the stew, the more likely you are to develop a cramp, he explains.

What we found was that dehydrating people by 3% and trying to cause cramps on a rested, unexercised muscle, people were just as easily crampable when they were really hydrated as when they were dehydrated.

Fatigue, dehydration, and new factors in exercise-associated muscle cramping

Miller’s laboratory work over the past 15 years has disrupted the traditional view of EAMCs that tended to be more observational in nature and conducted in occupational settings. Rather than observing workers building the Hoover Dam in the 1930s, in one study, published in 2010, Miller’s team asked subjects to sit on a semi-recumbent bike and cycle with one leg. They cycled until they’d lost 3% of their body mass via sweating, and then the team induced muscle cramps in the rested leg.

The aim of this study was to “separate the effects of dehydration from fatigue,” Miller explains. Inducing a cramp on a muscle that wasn’t fatigued by exercise was intended to approximate that process. “What we found was that dehydrating people by 3% and trying to cause cramps on a rested, unexercised muscle, people were just as easily crampable when they were really hydrated as when they were dehydrated.”

A subsequent study took participants to 5% dehydration and got the same results.

To alleviate the cramps, Miller and his team gave some of the participants 80 milliliters (about 2.7 ounces) of pickle juice. “This was just straight-up strained Vlasic pickle juice that I bought at Sam’s Club,” he says. While subjects were cramping, they drank either the pickle juice shot or deionized water – just plain, pure water that’s been stripped of all minerals. “And then we measured how long the cramps lasted after they drank the pickle juice versus the water.” A control group drank nothing.

“What we found was the pickle juice reduced cramp duration by 40% and it shortened the cramp’s duration much faster than water and nothing at all,” Miller says. Because the response was so immediate – it took about 90 seconds for the cramp to resolve in the pickle juice group – and so much faster than the typical 25 minutes it takes for pickle juice to be digested and work its way through the circulatory system, the team hypothesized that something was transpiring well outside the stomach to make the presumed cause-and-effect they were seeing.

“We proposed there was some kind of reflex happening in the mouth. That reflex still needs to be studied,” Miller says. A placebo effect also couldn’t be discounted, but Miller says he thinks the shock to the system that a shot of pickle brine or vinegar provides can work to distract the central nervous system enough to get the cramp to reset.

This concept has since led to the development of products like HotShot, a liquid supplement that contains high levels of capsaicin, which is the spicy compound in hot peppers. (Miller says he consulted with the HotShot company early on, and the company subsequently worked with researchers at Penn State University to test the product.)

“There’s something about vinegar and mustard and capsaicin – these are really intense sensory experiences,” he says, likening the effect to slamming your hand in a car door and then pinching your skin at the elbow to help alleviate that pain; the misdirection gives your brain something else to focus on so your hand seems to hurt less. “If your brain is sending all these signals, and then it hits this pickle juice or shot of capsaicin, it’s like, ‘whoa, what the hell was that?’ and that interrupts that excitation signaling” in the cramped muscle.

RELATED: Why These Areas Are The Most Common For Cramping

Cramping culprit: Changes in the central nervous system?

One insight Miller has elucidated is that for many folks, one cramp often leads to another. This common occurrence is likely related to how nerves become more excitable when they’re activated, and indicates that cramping causes changes in the central nervous system.

“It seems when you remove all the stuff associated with exercise and you just make people cramp, the cramp itself seems to alter the central nervous system, and that makes people more prone to future cramps once you get that first cramp,” Miller explains. This “is a major disappointment,” he adds, “but it explains an observation that we see very commonly in athletes.”

This finding adds to the idea that cramping is multifactorial, he says. “Now that you’ve hit that threshold and you haven’t given your body enough time to recover and lower itself from that threshold, then you remain prone to future cramps until you so something that attacks those factors that led to the cramp in the first place.” He says the body remains in that primed-to-cramp state for up to an hour after each cramp.

Over the next decade or longer, Miller expects research into cramping will aim to determine exactly how the central nervous system alters during and after a cramp and to pinpoint how each factor contributes to the development of cramp.

Induced vs. spontaneous cramps

In conducting cramp research, Miller and his group induce cramps with electrical stimulation. They place a small electrode over the posterior tibial nerve – that’s the nerve that runs down the inside part of the ankle around the bony medial malleolus bump. That nerve provides sensation to the bottom of the foot and the big toe, which is the muscle they’re trying to cramp during these studies.

Now, if most often your EAMCs occur in the calf muscle, you might be wondering why researchers aren’t trying to get it to cramp in the lab. The reason is because it’s “much more painful, and it’s a lot harder for people in a lab setting to tolerate than a big toe cramp,” Miller says.

But Maughan says studies that rely on induced cramps for their findings may be looking at the wrong thing. Cramps that arise because of electrical stimulation occur independent of exercise, sweating, and other factors.

“It’s not the same cramp that marathon runners get,” Maughan argues. “While it’s an interesting model, it’s a different story. In this artificial model of muscle cramp, water and salt balance don’t seem to be an issue, but to me, there’s a big disjoint between those two situations.”

Maughan says that while he respects the work that Miller and Schwellnus have done and maintains friendships with them, he says he thinks they have “misunderstood the fundamental problem, that there are different types of cramp. I’m interested in the spontaneous cramp that people get from exercise, and I think the evidence says there’s a disturbance of water and salt balance.”

How to banish cramps in a workout or race

No matter what’s triggered a cramp, you’ll no doubt want to get rid of it as quickly as possible. However, because cramping is a multifactorial process that’s unique for each person, treatments will also need to be tailored to the individual. In terms of alleviating muscle cramps in an individual athlete, anecdotal evidence reigns supreme.

“Hydration might work for you, but it might not work for me,” Miller says. “And so if we change our thinking about what causes cramping to individualize the recipe, then I think it explains a lot better the published findings that one treatment doesn’t work or another does,” he says.

In other words, if you find that you cramp frequently, you’re going to need to do a little homework to unravel what your triggers are and how best to address them. “We’re not all the same. We’re not all robots,” Miller says.

Though they might be on different sides of the hypothesis equation, Maughan and Miller do share some views about coping with muscle cramps, namely that you have to figure out for yourself what works best.

Start with your hydration plan

“Different things will work for different people,” Maughan says. “For most people, the starting point is looking at whether you’re drinking enough or too much.” He recommends assessing your overall hydration level, determining whether you’re losing a lot of salt during exercise, and trying different solutions until you find one that works.

RELATED: Dehydration Makes Any Effort Feel Harder

He recommends starting with less-expensive options like pickle juice first before “wasting a lot of money on expensive products that probably don’t work.”

Keep a cramp journal

While scientists work on answering the age-old question of why we cramp, one of the best things you can do is keep a cramp journal. If you cramp during a workout, write down when it occurred, how long it lasted, at which point during your session it transpired, and other relevant information such as how rested, hydrated, and fed you were when it happened. Did you push harder than usually during your session? Did you drink alcohol the night before? Consider everything, and write it down. Do this every time you cramp, and over time, you may notice a pattern.

With that information, you can alter your behavior leading into the next workout or experiment with different remedies until you find the one that works best for your cramping recipe. “There is no cookie-cutter approach that will help everybody,” Miller says. “Everybody’s unique, and you have to do your homework.”

Rule out any underlying causes

It’s also wise to check with your doctor before you go all-in on one cure or another. “Before you start throwing stuff into your body, talk to your doctor,” Miller says. Particularly if you have high blood pressure, for example, the salt content in pickle brine might not be advisable. “Drinking pickle juice is like drinking the equivalent of ocean water. Drinking large amounts of it frequently probably isn’t great for your blood pressure.” (Miller notes that in the lab, they use the equivalent of about two shot glasses full of pickle juice, a very small volume that doesn’t impact blood levels. However large volumes would impact blood sodium levels and elevate blood pressure.)

It’s also important to rule out any undiagnosed medical conditions that could be causing the cramping, such as diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, hypothyroidism, or Machado-Joseph’s disease.

Think like a scientist

Though both Miller and Maughan each make compelling arguments for their positions, the complete picture of cramping likely involves elements of both their work. At the moment, the best advice they can offer any athlete who occasionally experiences this kind of discomfort and inconvenience is think like a scientist. Experiment in your training to learn what works best for you to alleviate the problems. If that’s gulping down an electrolyte-laden sports drink, do it. If it’s stretching the muscle counter to the cramp or taking a break in your exercise, then do that.

Because at the end of the day, what works best for your cramps will likely be different from what works to alleviate someone else’s cramps. Remember, it’s all about your personal “recipe” for cramping, as they say – and weirdly enough, that recipe might include pickle juice.

RELATED: Women’s Running Complete Collection of Food And Nutrition For Runners