Products You May Like

“If you want someone who can splint a femur in the dark during a blood-moon eclipse while training a rookie on a 50-degree slope and backboarding the guest into a toboggan to be belayed and skied out, you’re going to need someone with more than two years of experience,” says Brianna Hartzell, a former ski patroller at Stevens Pass, Wash.

It turns out that while some resort guests may see patrolling as a relaxed job that pays ski bums and retirees to carry around spools of rope while getting fresh tracks after every storm, patrollers are highly trained, severely underpaid workhorses who deal with unimaginable catastrophes and bizarre incidents nearly every day when they show up to work. From traumatic and fatal injuries to Darwinian stupidity to downright criminal activity, war stories are a dime a dozen on ski patrol.

Also Read: In Warren Miller’s “Winter Starts Now,” the Future of Ski Patrol is Female

“We once found a snowboarder in the woods, strapped in and hanging completely upside down with the tips of his board wedged between two trees,” says Joe Naunchik, who worked on Park City Resort’s ski patrol for 12 years. “I still have no idea how he ended up in that position.”

Asking a ski patroller to tell their favorite story is like asking a librarian to pick their favorite book. It’s overwhelming for them to even consider. The stories, like the years, tend to blend together and slosh around in a bank of après-ski party memories, like when that veteran jumped the patrol shack in a rescue sled while naked except for a helmet made of beer cans at a time and location we are not at liberty to disclose. But for every fun tale there’s usually a dark one, along with an event so ridiculous it’s hard to believe it even happened.

So next time you’re thinking about ducking a rope or sliding down the slopes on a cafeteria tray, consider what other absurdities ski patrol might have already dealt with before lunch. These five preposterous stories will give you a pretty good idea.

All That Remains

As Told By: Brianna Hartzell

Location: Stevens Pass, Wash.

Year: 2018

In the spring of 2018, after a couple of days staring across the hill at a dark, discolored patch of snow, it was time to go check it out. The grey spot was visible from the patrol shack at the top of the 7th Heaven lift, and although it looked like residue from avalanche control explosives, this area of the mountain called Shim’s Meadow was double-black-diamond terrain off the beaten path, and with no recent snowfall, we hadn’t bombed the slopes in a week. That stuff is water-soluble, so it would have dissolved by then.

There was a telemark race going on right below it, so another patroller, Peter, and I planned to ski a lap through the course after checking out the mysterious spot that had caught our attention. The patch was about the size of a living room rug, four to five feet in each direction. The grey, dusty stuff was mixed in with the snow, having melted the surface faster by absorbing more heat from the sun. Peter skied into the pile, the sloppy snow covering his skis and boots, and scooped up a handful to examine. I stood just next to it while we both tried to figure out what the hell it was. Spring snow gets dirty, but not in one place like that. Peter was smelling it and one of us made a joke that he should taste test it.

Then he picked out a small, jagged white chunk. “What IS that?” he asked, holding it up. “That’s a tooth!” I said with wide eyes. It was definitely a human molar.

There was no screaming. We just froze. It was one of those moments of realization where we made eye contact and it all just set in for both of us that Peter was standing there holding a handful of human remains from what appeared to be a botched cremation. I’ve only seen cremated remains a couple of times but I’ve never seen any chunks in it.

We were horrified, but still did a lap through the telemark course while Peter kept looking at the wet ash stuck to his gloves. I had some bits clinging to the cuffs of my pants. Peter and our patrol director went back and respectfully shoveled most of the remains into the nearby trees so dozens of other people wouldn’t ski through it. We never found out whose remains they were. Although we didn’t like the thought of digging up and moving someone’s final resting place, it was an understandably beautiful place to have one’s ashes spread.

Related: Are You Good Enough to Be a Patroller?

Lift Line Confrontation

As Told By: Conor Roland-Chivara

Location: Alyeska Resort, Alaska

Year: 2017

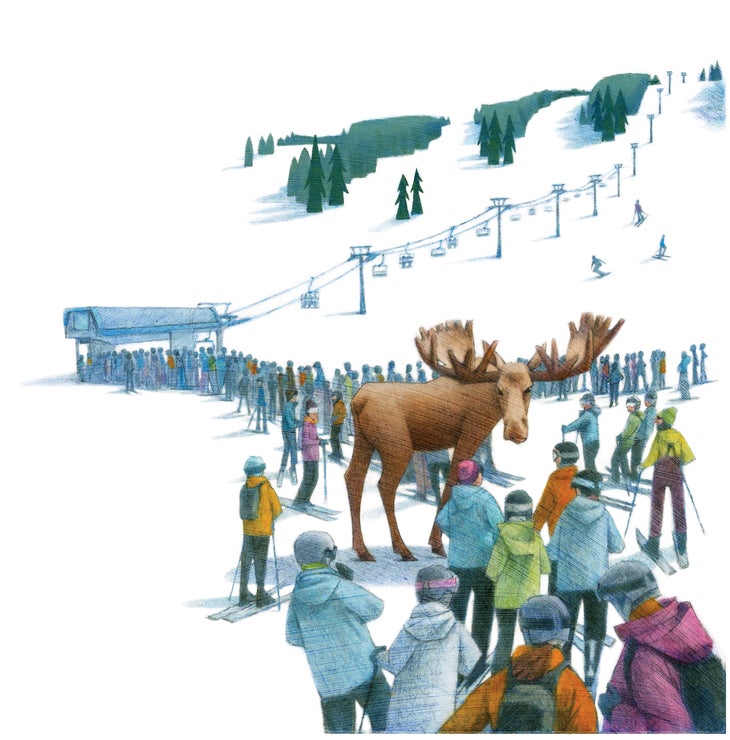

My first year on ski patrol was 2017, and I saw a lot of wild, gnarly stuff, including some traumatic injuries to humans. We didn’t have to deal with too many confrontations, except for a week in March that saw slowly accumulating tensions with a young male moose. For a few days, there was some radio chatter about him coming onto the resort in the middle of the day and getting close to the lift line at Chair 6, which made guests pretty uneasy. We tried to push him out of the area with snowcats, which worked for a little while, but he’d come back outside of operational hours. He soon got accustomed to us trying to scare him off and wasn’t having it anymore.

One day, at about 2 p.m., the moose came back out of the woods and cruised into the maze with the skiers as if he was lining up to get on the lift. When people started to avoid and clear the area, the moose picked up on the tension and started to snort and stomp his feet. One other rookie and one veteran patroller went down to the lift where the moose was now running around, knocking over the corrals and terrorizing guests. We tried using bear spray to get him to leave. Amidst the calamity and confusion, they managed to hit the moose with some of the bear spray, but a slight breeze blew much of it back onto themselves, getting on their faces and in their lungs and such. The moose fled, but the patrollers both had to be taken off the mountain and driven home for the day.

By this time, videos of the moose charging the lift line were going viral on social media and it was lucky someone hadn’t been trampled or hurt, so management decided that if he came back the next day, they would take mitigative action for the safety of the guests.

The next day, the moose returned to Chair 6, getting confrontational, charging the line, and spoiling for a fight. We encouraged him down the groomed runs with a snowcat and into the woods near the base. That’s when Eric Teixman, the assistant director of mountain operations, followed the moose into the woods with a shotgun. Two shots rang out, followed by some commotion in the woods, and the moose was down, some 50 feet away from the trail. Then they had to get it out of there, so they strung him up to the cat’s winch cable and dragged him onto the run, scooping the body into the bucket and hauling it off, leaving a large patch of blood on an intermediate slope and a trail of red sludge marking the snow all the way out to the road.

The moose ended up going on the state roadkill list, meaning a family was able to eat the meat and nothing went to waste. Afterwards, because of the viral video attention, guests expressed a lot of concern about moose for weeks. We constantly had to assure guests that we had a mitigation plan in place should another animal attempt to endanger itself or the guests again.

Mountain Mayhem

As Told By: Aaron Smith

Location: Aspen Snowmass, Colo.

Year: 1995

I was a second-year patroller in 1995 at Highlands, living the dream in Aspen’s heyday. One evening, a bunch of us were in the iconic Chewy’s bar at the base for several hours of après when a solo skier was reported missing just outside of the resort boundary. He was cliffed out on the Maroon Creek side of the mountain below Olympic Bowl, unable to get down. There are only one or two routes through those cliff bands and you need to know your way, which he did not. So at around 7 p.m., snow safety director Kevin Heineken came in and pulled a handful of patrollers straight out of the bar as we chugged the last of our beers and went out to mount a rescue. (It was the ’90s. We’ve improved operational procedures since then.)

Skiing outside of the resort boundaries was still pretty new at the time and not many people were familiar with the terrain, including the volunteer mountain rescue team. They showed up with big, heavy packs and needed us to shuttle them up with snowmobiles alongside patrollers running snow safety control in the avalanche terrain. Having two different entities there erupted into mass confusion.

I was one of the sled operators. Since we didn’t have incident command systems at the time, let alone designated snowmobile routes, I almost collided head-on with Kevin Hagerty and his passenger at a blind rollover on Prospector. I had to throw the sled on its side to miss them and the machine slid down to Puppy Point. Meanwhile, Pat “Duffy” Duffield was one of the other shuttlers and he was known to be a terrible sled operator at the time. He was riding up Jerome at probably 40 mph when the front skis came off the snow, so he tried to turn the sled back downhill but fell off as it rode 400 yards down into a viewing platform where a bunch of new real estate was under construction. He chased after it and got back on, only to ride it off a 12-foot retaining wall where it got stuck in the snow and had to be dug out the next day. It was a shitshow.

Three patrollers went down into the gully with a handful of mountain rescue guys. They were on skinny tele skis in waist-deep facets, which was a recipe for disaster and made snow travel quite tedious. Once they located the victim, who’d been stuck on the cliff for eight hours waiting for someone to show him how to sidestep down it, the avalanche control teams began blasting the slope below them with explosives to manage the committing terrain on their way out. No one made it home until at least 3 a.m.

As this was all happening, I was spotting the whole thing from Maroon Creek Road. It was still that cowboy era and I was in my early 20s, half cocked, standing there watching an out-of-bounds rescue in gnarly ski terrain with bombs going off in the darkness and I remember thinking, “This job is badass! I’ve found my calling.”

The Jumper

As Told By: Bill Dowell

Location: Crested Butte Mountain Resort, Colo.

Year: 2007

Ten or fifteen years ago, a teenage kid was caught poaching fresh tracks beyond our roped boundary in an avalanche-prone area. We followed his tracks, brought him back inbounds, and I rode up the Teocalli lift with the kid to escort him back to the base area. He said he was sorry, but didn’t sound sincere. We sat on the old center pole double lift as I explained to him what was going to happen, how we were going to call the police who would take his statement and give him a misdemeanor ticket as someone from management read him the Colorado Skier Safety Act. Once we were about halfway up, cresting over a hump that was 12 to 15 feet below the lift, he looked at me and said, “I gotta go for it” and jumped off the chair, landing on soft snow below and side stepping into the woods. It certainly surprised me and I didn’t really consider jumping after him, but I remember looking down and saying, “We’re going to get you.”

I put the call out on the radio, thinking he’d try to ski through the woods towards the base area and disappear into the crowd. A patroller and an off-duty lift mechanic followed his tracks, which involved a lot more sidestepping than he probably thought. He made his way into a new subdivision under construction on the side of the resort just below Gus’s Way and hid in an unfinished basement. Our guys were closing in on his tracks, but once he got into the neighborhood, we didn’t know where he went.

He might have gotten away with it, but at this same time, we were dealing with a serious injury on the hill that required an ambulance to drive directly up to the Gold Link Lift area for a direct patient transfer. When he heard the ambulance siren, the kid thought it was the cops coming to bust him and get him into even more trouble for fleeing, so he freaked out and ran out of the basement hiding spot, surrendering to the patrollers and turning himself in. I bet he’s sorry now.

Mammoth Meth Foot

As Told By: Josh Feinberg

Location: Mammoth Mountain, Calif.

Year: 2004

I was a third-year patroller in February 2004, and hadn’t been on many out-of-bounds rescue missions until the day we got a call about a missing snowboarder. One of his friends hadn’t seen him in a day or two and his stuff was still in his hotel room. We split up into four teams of two or three patrollers and began looking off the backside for tracks. My team found snowboard tracks just beyond a well-marked boundary. You’d definitely know you were crossing it, but once you get going, it’s a lot of work to get back inbounds. The terrain runs south and west, towards Red’s Meadow, where there’s a road that occasionally gets groomed, but if you miss the meadow and go between it and Mammoth Lakes Basin, you likely won’t hit anything for 50 miles until Fresno.

We followed the snowboard tracks farther down in this direction for a few hours and even found a gum wrapper, but we didn’t have skins so the farther out we went, the harder it would be to get back. This was mid-winter and the temperatures were down to -20 Fahrenheit that week. At one point, around Rainbow Falls, the board tracks became footprints that went into a river and up the embankment on the other side. It was an odd choice considering that we could see the top of the gondola station from there in the opposite direction. I figured he was exhausted from moving through the snow so much and he thought he could find another way out by continuing down.

We wanted to keep following the tracks to find the guy, dead or alive, but at that point we were almost too deep to get ourselves out, so we sidestepped a ways back to the road and got picked up. As I climbed into the snowcat, I remember thinking, “Why the hell did he go into the river?”

Later, we learned that he was a former Olympic hockey player who’d been high on methamphetamine for several days. Hearing about the drugs, it made more sense. He’d been mentally altered while getting himself more and more lost, ultimately walking nine miles in the wrong direction. He tried nibbling on bark and pine seeds for energy. When he peeled his socks off of his wet, frostbitten feet on day three, strips of flesh were clinging to them. In his delirium, he ate pieces of his own feet. By the time the National Guard spotted him from a helicopter on his eighth day missing, his body temperature was down to 86 degrees, he’d lost 40 pounds, and damaged his feet so badly they both had to be amputated.

I think they made a movie about him and I heard he was on “The Oprah Winfrey Show,” telling his cautionary tale. We see dozens of people each year getting lost off the back side, but most of the time we can find them and help them get back inbounds, especially now that we carry backcountry survival equipment that allows us to go further. To have someone stay out there for multiple days and survive is rare. Years ago we found a pair of ski boots that still had someone’s foot and leg bones in them. The rest of their body was eaten away by critters.

More Long Reads from SKI

This is How You Get Extreme in Taos, N.M.

At Maine’s Shawnee Peak, Longtime Rivals Battle For More Than Gold

Science Confirms What Skiers Already Knew: Time in the Mountains Shapes Who We Are