Products You May Like

Receive $50 off an eligible $100 purchase at the Outside Shop, where you’ll find gear for all your adventures outdoors.

Sign up for Outside+ today.

Editor’s Note: Since the establishment of the United States’ national parks, visitors have been making questionable choices with animals and natural features, and that hasn’t changed much in the six years since we published this story. We’re resharing it now for a little bit of historical context into the bad decisions the bison-selfie crowd is still making now.

When two Yellowstone tourists put a baby bison in their car in May 2016, indirectly causing the animal’s death, commentators pointed to it as the latest example of a society that had lost touch with the wilderness. “The important thing is, these tourists got great pictures of a baby bison in their car, you know, for their Facebook,” wrote one commenter on Backpacker’s Facebook page. “Isn’t that all that matters anymore?”

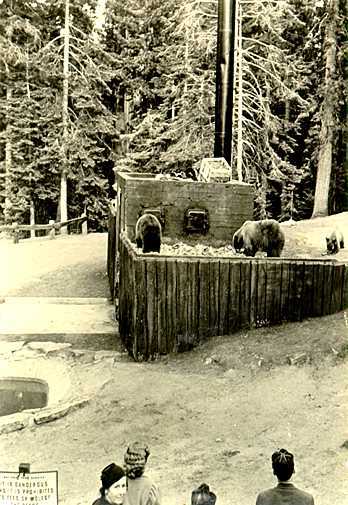

Read the headlines, and it might seem like our parks are under siege by tourists with more tech than common sense. There’s a grain of truth in that. (Don’t believe us? Google ‘bison selfies.’) But while the iPhones may be new, the boneheaded humans aren’t. Since the establishment of our first national park in 1872, there have been visitors who acted first and thought, well, never. What’s more surprising is that tourists are getting up to almost exactly the same kinds of trouble today that they were a century ago.

Read the headlines, and it might seem like our parks are under siege by tourists with more tech than common sense. There’s a grain of truth in that. (Don’t believe us? Google ‘bison selfies.’) But while the iPhones may be new, the boneheaded humans aren’t. Since the establishment of our first national park in 1872, there have been visitors who acted first and thought, well, never. What’s more surprising is that tourists are getting up to almost exactly the same kinds of trouble today that they were a century ago.

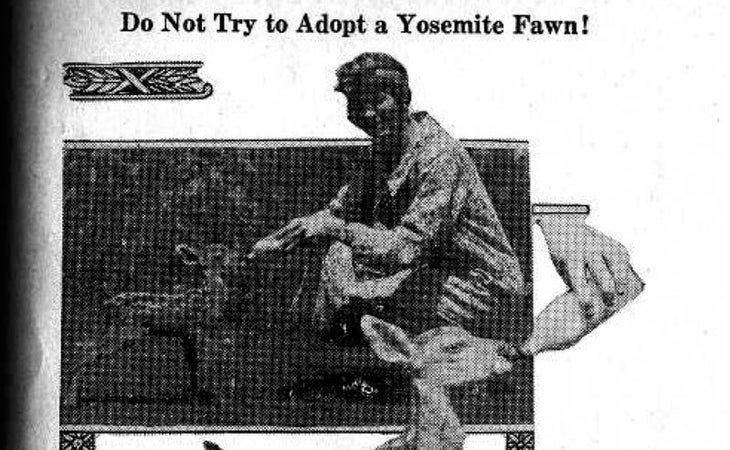

In the fall of 1927, Yosemite National Park’s rangers faced a crisis: The park’s baby deer were disappearing. “As is usually the case at this time of year, Yosemite visitors find it difficult to resist the temptation to adopt a cunning pet in the form of a mule deer fawn,” the September, 1927 edition of Yosemite Nature Notes, the park’s monthly journal, reported.

One particular instance of such “unnecessary compassion” sounds depressingly familiar. “Ranger [John] Bingaman, in charge ofSoda Springs checking station, noticed an animal in the lap of a woman in a car passing through his station. He asked if it was a dog and the woman replied, ‘No, it is a fawn with a broken leg. We are going to take it to San Francisco and have a splint put on its injured limb.’”

Ranger Bingaman confiscated the doe and examined its leg. It was not broken.

Like their colleagues today, the rangers attempted to return the doe to the wild. Now habituated, the animal would not have it; it followed the rangers back to their vehicle multiple times. Only after making a mad dash away did the rangers successfully lose it.

Like their colleagues today, the rangers attempted to return the doe to the wild. Now habituated, the animal would not have it; it followed the rangers back to their vehicle multiple times. Only after making a mad dash away did the rangers successfully lose it.

Just over a week after the baby bison incident this May, Yellowstone witnessed another spectacular display of bad judgment when a group of four Canadian viral filmmakers were photographed walking on Grand Prismatic Spring, which can reach a scalding 160 F. While three of them now face criminal charges, they escaped injury. But not all wanderers have been so lucky.

Take the story of Thumb Hotel concession stand worker Henry Muedeking, reported on August 31, 1893, by The Columbian of Columbia Falls, Montana. On one moonlit night in June, Muedeking decided to take two lady friends of his for a stroll down by the geysers. After wandering deep into the field, the trio began “monkeying around on the formation.” The night got a lot less fun when the crust collapsed, plunging Muedeking into the scalding water surrounding Thumb Geyser. “When help arrived,” The Columbian reported, “he was found lying beside the seething pool with the flesh boiled from his legs.” Muedeking survived the encounter, though not without serious injuries. After recuperating for two months at Fort Yellowstone hospital, he was still unable to walk.

Originally published May 2016; last updated February 2022