Products You May Like

Get full access to Outside Learn, our online education hub featuring in-depth fitness, nutrition, and adventure courses and more than 2,000 instructional videos when you sign up for Outside+

Sign up for Outside+ today.

“You guys got gaiters?” asked a gruff voice from behind.

An old timer with a scruffy white beard under a Royal Canadian Navy hat stood in the back of the line with a toothpick protruding from the grin on his face. He watched our group of four backpackers buying last-minute candy bars at the Pacheedaht Campground office in Port Renfrew, British Columbia, on the southwest end of Vancouver Island. Indeed, we had packed gaiters, hoping to deflect mud and late-May rainfall from entering our boots, and one of us gave him a sheepish nod.

“How about an orange tarp with a black spot in the middle for a helicopter rescue?” Now he was just trying to scare us—maybe. “Make sure you get past Owen Point before the tide rises or you’ll be climbing a couple hundred feet straight up through thick mud to get around it on land.”

“Can you see remnants of the shipwreck out there?” I asked, exposing my naivete.

He raised an eyebrow. “Which one?”

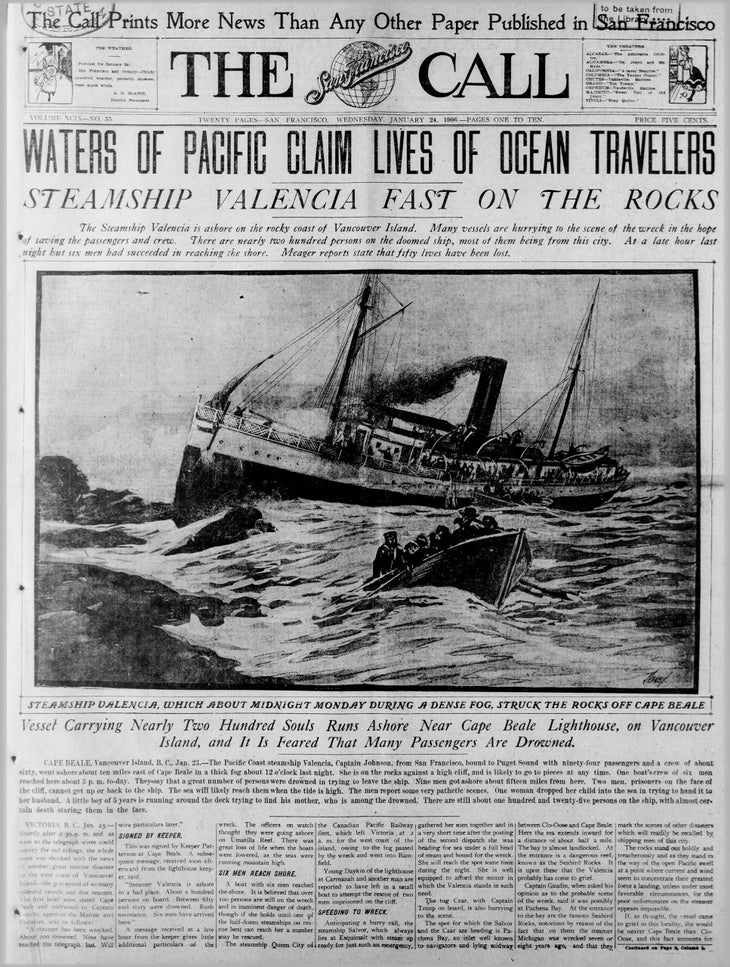

Minutes later, we were standing outside the office in drizzling rain at a mandatory briefing for hikers embarking on the six- to eight-day, 46.6-mile West Coast Trail between Gordon River and Pachena Bay in Canada’s Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. After warnings of mountain lions stalking hikers and an explanation of the tide chart, a ranger handed everyone a waterproof map of the lumpy coastline dotted with 29 small icons of what appeared to be sinking boats. The map’s legend denoted these as shipwreck sites from the 19th and 20th centuries. Schooners, windjammers, freighters, fishing vessels, and steamships had all run aground or sunk in what’s known as the Graveyard of the Pacific. This treacherous stretch of coastline from Tillamook, Oregon, to the northern tip of Vancouver Island is notorious for violent currents and unpredictable weather that have shredded steel ships down to piles of rust. Most of the people aboard when these accidents occurred survived, while a few vessels saw several crew members perish. But at kilometer 18, below sheer, coastal cliff walls, the SS Valencia found its final resting place just before midnight on Monday, January 22, 1906. Nearly eighty percent of the 173 passengers and crew members died in a 36-hour nightmare. The trail we were about to hike was the rescue trail established by the Canadian government in response to the tragedy. The hope was to ensure that nothing like it ever happened again, and that, according to a U.S. government report released after the fact, “the victims of the Valencia will not have perished in vain.”

After a short ferry ride in a metal boat to a stony beach from a Pacheedaht First Nation local, our hike began with a wooden ladder. The two-by-four rungs were slippery and precarious, ascending 30 vertical feet into a lush temperate rainforest with 100-year-old beech trees. It took several hours to adjust to the trail’s wet, off-camber footing over exposed roots and rocks. Boot-sucking mud caked our feet and abolished any traction. Sunrays penetrated the treetops and late morning mist as we flopped through the soggy obstacle course. The dense vegetation seemed to be fighting to reclaim the path, and whacked us in the face and shins as we wound around car-sized cedar trees and dipped into steep, eroding ravines.

As I slipped on a root and fell onto my butt for the fifth time in the first hour, I wondered aloud, “Is this really the best way they could find to get through here?” Then I saw the collapsing bridges with moss-covered wood that had deteriorated to mush and crumbled into the streams and mud pits below, sometimes on top of the previous bridge that was still decomposing. The area sees over 11 feet of precipitation each year, and it’s clearly a

Sisyphean task to keep the trail passable, especially with storms like the ones in 2006 and 2007 that downed an estimated 3,000 trees and took out major trail infrastructure with a massive landslide. Since 1973, Parks Canada has built and maintained 130 of these bridges along with 70 ladders and four river-crossing cable cars to preserve a trail that requires as much scrambling, balancing, and bushwhacking as hiking. Parks Canada still relies heavily on this trail as a rescue route for shipwreck victims, and many have long believed the area to be cursed by the spirits of those lives lost.

We woke up from our first night camping in a wooded recess at Thrasher Cove with a beachfront view of Washington’s Cape Flattery across the Strait of Juan De Fuca. After waiting until early afternoon for the tide to drop enough to pass Owen Point, we were soon clambering on all fours over snarls of gargantuan driftwood scattered like toothpicks down a 5-kilometer stretch of slimy boulders. It felt more like spelunking with 50-pound packs than hiking. This “beach” section posed at least as much threat of injury as the inland trail with a full menu of ankle- and knee-twisting crevices served up in every step. Crawling along at this 1-kph pace back into the forest, I shuddered at the thought of how long an emergency rescue would take and how complicated an extraction would be, especially after descending the eight separate ladders to get down to Cullite Creek on our third day.

Fortunately, Parks Canada has much more technology and resources at their disposal than what existed in 1906, and they execute an average of 80 to 100 rescues of hikers (and the occasional shipwreck victim) from the trail annually. “Over six-plus days of hiking, the trail takes a toll on people’s bodies and minds, and most have a hard time staying focused, especially with the beautiful scenery, and folks just misstep and get hurt,” says Randy Mercer, Visitor Safety Technician with Parks Canada in Port Renfrew. “The environment is the same since the time of the Valencia and weather often hampers rescues. In the easiest scenario with a minor medical issue and good conditions with a boat nearby, you’re still looking at a minimum of four hours from start to finish. Some have been up to three days trying to get somebody out while crawling along with a stretcher at 100 meters per hour.”

Once the thick fog and squalls of rain roll in and the boats and landmarks at sea fade out of sight, the eeriness of this supposedly haunted coastline sets in.

By the time it set off from Meigs Wharf Embarcadero in San Francisco on Saturday, January 20, 1906, the 1,598-ton, double-masted, iron steamship SS Valencia had already survived an attack from the Spanish cruiser Reina Mercedes off Guantanamo Bay, a collision with a steamer in Elliott Bay off Seattle, a running-aground in Alaska near the Yukon River Delta, and a series of embezzlement scandals at the hands of its owners. Built in 1882, it was 252 feet long, equipped with six lifeboats, a work boat, and two life rafts. Some of the crew considered the Valencia unlucky; the cook had a premonition of disaster but joined the trip anyway.

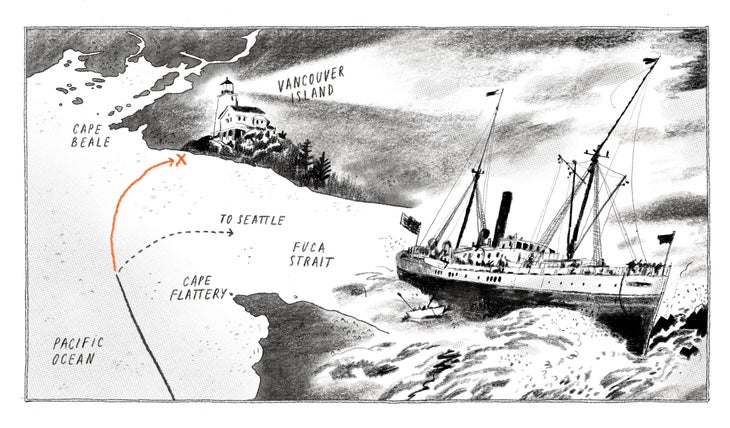

A crowd of friends and relatives had seen it off, waving hats and handkerchiefs, as smoke billowed from the ship’s stack and she started the three-day journey to Victoria then on to Seattle. Cruising at 11 knots, it passed Cape Mendicino at 5:30 a.m. the next day and found itself shrouded in a thick fog. With no view of the stars for navigation, 40-year-old Norwegian Captain Oscar Marcus Johnson relied on dead reckoning—using estimated speed and time from a previously determined position—to calculate the ship’s location, but he did not account for the strong, northerly Davidson current. The first clue that they were off course was when their soundings—a depth measurement with a long line—quickly dropped by half. Minutes later, one of the officers saw a black shape take form in the fog. The SS Valencia’s orders to turn west came too late, and it crashed into the Walla Walla Reef east of Pachena Point on Vancouver Island.

“By God! Where are we?” were the words of Captain Johnson when the ship first struck the rocks and immediately began taking on several feet of water by the minute. Not even he realized that they’d completely missed the eastward turn for the 12-mile entrance into the Strait of Juan De Fuca and slammed into the Canadian shoreline.

To keep the ship from sinking, Captain Johnson ordered it full speed astern in an attempt to beach it, but a vicious storm was now raging and the waves rocked the boat onto a craggy shelf, lodged in place almost 100 feet from shore.

Chaos ensued. Large waves bashed the ship into the reef. The details are vague, but it’s reported that the sailors below deck never received an order to launch the lifeboats. Passengers and unqualified crewmen, including waiters and firemen, piled into three lifeboats in a panic and began dropping them into the water with abandon, causing the boats to nosedive and eject bodies into the freezing sea. All but one of the passengers on these first boats drowned. At one point, a mother was passing her baby down from the ship to her husband on a lifeboat when a wave rammed in, causing her to drop the child into the ocean between them. Two other boats launched more successfully but rolled in the violent waves and only nine of the 20 or 30 men made it to shore 500 yards up the coast. They spent a miserable night shivering on the cliffs before scaling them the next day and finding a telegraph line to send for rescue ships.

Back at the SS Valencia, a third lifeboat launched and disappeared past the breakers. Captain Johnson blew three fingers off his hand trying to signal for help with a flare gun. He ordered the fourth lifeboat, led by boatswain Timothy McCarthy, to get to shore and string up a heavy rope for extracting passengers from the wreck with a breeches buoy—a zipline-like rescue device. That boat lost several oars while trying to launch and drifted 7 miles up the coast before landing safely on shore, but instead of trudging back to the ship as ordered, they also followed the telegraph line west to a light station at Cape Beale to call for help. It was Tuesday afternoon by then, and rescue ships would arrive much too late. It’s impossible to say how many more lives they would have saved had the men made it back to the Valencia and secured the line between ship and land.

“After struggling through the dense underbrush and skirting insurmountable perpendicular cliffs, I can truthfully say that we could not have progressed a mile a month toward the Valencia,” McCarthy, who survived, later told the Seattle Star newspaper. “The underbrush was so thick and impenetrable that it was simply beyond human strength to force one’s way through the tough tangle. We tried time after time to make our way seaward through that devilish growth, but could make no impression against it.”

At 9:20 a.m. on Wednesday, the first of four rescue ships came into view within 2 miles of the wreck, which sat in water too shallow for the vessels to reach. The Valencia launched two life rafts to meet them. The first, which included the cook with the premonition of doom, tried to row out past the breakers to the ships but missed them and drifted 17 miles out to sea, landing on an island where four of 10 men survived and were later rescued. The second raft was loaded to capacity with 18 men. Despite their pleas, no women could be convinced to board after the carnage they’d witnessed. The women chose to remain on board in the freezing rain and wait for rescue, reportedly singing “Nearer My God to Thee,” while the men on the life raft made it to one of the other ships. The remaining vessels dared not come in closer to the calamity and eventually sailed away, leaving the remaining passengers to perish.

“That’s his heart. It’s still beating,” said Hippie Doug, a ponytailed ferry operator at Nitinaht Narrows, as he ripped the shell off a live lake crab and flicked the rest of the guts into the river. Day five on our hike brought us to the Crab Shack, a Whyac First Nation-run restaurant on a floating dock, for a pricey lunch of seafood and loaded baked potatoes by a warm wood stove. Hippie Doug was telling stories and jokes while prepping crab and halibut and passing around his personal photo album. When I asked what he knew about local shipwrecks, he casually mentioned that a fishing boat had just wrecked at the nearby inlet that week and one of the three passengers was still missing. Waves 2 to 3 meters high and winds up to 30 knots capsized the boat when it got too close to shore. Even today, with GPS, radar, electronic sounding, and more advanced nautical charting, it felt as if the seas here were as determined to claim mariners’ lives as the forest was to claim the bridges and treadpath.

That rugged, harsh terrain sure does make for a spectacular hiking experience, though. On top of the deep mud and creek crossings, slip-and-slide rocks, elevated root tangles, and pounding rainstorms, we’d spent days prancing along the beach, balancing across slick logs strewn over tidepools and coated in barnacles and mussels wrapped in kelp and dotted with periwinkles. Crustaceans scurried around our boots on sandstone slabs carved into massive surge channels and carpeted in bright green algae. On the inland portions of the trail, sword fern and skunk lettuce appeared glued to every surface while new trees grew out of still-rotting logs and 6-inch slugs were hard at work sliming and decomposing every inch of wood in sight. At times it felt less like walking and more like hopping through a video game, pole dancing around soggy trees while trying to guess which trick log wouldn’t sink under our feet and dunk a boot into a dark puddle. Then we’d emerge from the forest onto a dry boardwalk through an open air marsh or a pebble beach with views out to sea. We strolled through overhead caves and rock arches coated in rainbows of multicolored lichen while avoiding those with bear and cougar paw prints at their entrances.

Weathered, discarded buoys hanging from beachfront trees signaled land access points for distressed seafarers and reminded us that this remote backpacking trail wasn’t made for backpackers. We were walking in the footsteps of First Nations people, shipwreck survivors, rescuers, lighthouse workers, and telegraph linemakers. Overland trails that existed here for generations would never have developed into backpacking trails were it not for all of these shipwrecks, especially the SS Valencia. According to Michael Neitzel’s book, The Tragedy of the Valencia, “This treacherous stretch of coast … had seen the destruction of 56 vessels with the loss of 711 lives in the 40 years before 1906.”

The same month the Valencia went down, President Theodore Roosevelt, then in his second term in office, commissioned an investigation into what was, at that point, six years before the sinking of Titanic, the worst maritime disaster in Canadian and U.S. history. The report, which came out on April 14, 1906, listed 11 recommendations for the U.S. coastline. Among those were the establishment of new lighthouses, motorized lifeboat stations, coastal escape routes and shelters, and studies on currents in the area. As the Canadian government enacted similar measures, they paid special attention to the establishment of the “lifesaving” West Coast Trail and infrastructure to make it more passable and navigable.

On day six, we pulled ourselves across the last cable car stretching 20 feet above the same wide, rushing Klanawa River that the three rescuers forded with a broken canoe in 1906. We’d stepped over rusted remnants of old ship debris and spotted a tarnished metal anchor lying on the beach, still as the seal carcass that crows were eating nearby. We passed a derelict donkey engine and arrived at the Valencia Bluffs overlook by late morning, high above the rocky shelf getting pounded with waves. This seemed like the worst imaginable place to be stuck. The cliffs were 100 feet tall and near vertical, almost overhanging, with shallow caves in which those Valencia passengers who’d made it to the icy shore that first night huddled, unable to scale the walls, until the tide rose and drowned them.

A few decades ago, what was left of the Valencia’s bow stood upright in the surf, but it has since turned upside down and now sits obscured 30 meters below the surface. Some of the propeller shaft and two big anchors are also submerged 20 to 40 meters deep and out of sight.

Also nowhere to be seen were the spooky illusions we’d heard about. On the way back into port aboard a rescue ship, the survivors claimed to see ghostly apparitions of the SS Valencia headed straight into the cliffs where it wrecked, doomed to the same fate, populated with skeletons hanging from the masts. In 1910, the Seattle Times reported a handful of other paranormal sightings of the phantom ship and its skeleton-manned lifeboats on foggy days. In 1933, 27 years after the tragedy, the Valenica’s number five lifeboat drifted ashore in Barkley Sound in inexplicably good condition with much of its original paint intact and the boat’s nameplate still affixed to its side.

Locals still say that shipwreck victims’ restless spirits haunt the Graveyard of the Pacific’s jagged shoreline, which is rumored to contain wreckage debris at every nautical mile. No matter how long we stare out into the heavy fog or take in the vast horizon beyond the thick, green forest, we’ll never know the terror that those men, women, and children carried to their graves at sea on that fatal day in 1906.

But as we ended our trip on the pristine, sandy beach of Pachena Bay with a peaceful breeze and soft sun drying our damp clothes, it all felt too heavenly to be haunted. If only the SS Valencia could have drifted into this protected cove, perhaps its passengers and crew would have witnessed some of the landscape’s natural splendor that we were so privileged to experience rather than such deadly horror. Instead, that tragedy gave way to this breathtaking trail—and the opportunity to revel in this place’s beauty instead of fear it.